What perceptions electrical engineers have on expertise and

scientific thinking – and how these perceptions are related to

learning

Kirsti Keltikangas

Helsinki University of Technology TKK, Faculty of Electronics, Communications and Automation

02015 TKK, Finland (kirsti.keltikangas@tkk.fi)

Abstract

This paper outlines a part of research underway at Helsinki University of Technology TKK. The

research is focused on electrical engineers and their perceptions on engineering expertise, scientific

thinking and how these perceptions are related to learning. Qualitative data collected in an Internet

survey were analysed using a content analysis method, and three categories were found: a learning view

category, a status category, and an individual/collective category. Furthermore, some common

competencies describing engineering expertise were found. These research results serve as a basis for

further research on engineering education.

Keywords: electrical engineers, expertise, scientific thinking, learning

1

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this paper is to introduce a part of an on-going research project on electrical engineers and their

perceptions on expertise and scientific thinking, and how these perceptions are related to learning. This research

is currently underway at Helsinki University of Technology TKK at the Faculty of Electronics, Communications

and Automation. The aim of this paper is to understand how engineers’ expertise in engineering and scientific

thinking is related to learning and developing their own competencies.

There is clearly a need to review the role of engineers and engineering education because they have in general

changed much during recent decades. Bordogna [1] has claimed that “tomorrow’s engineers will need to use

abstract and experiental learning, to work independently and in teams, and to meld engineering science and

engineering practice”. He adds that engineers “must exhibit more than first-rate technical and scientific skills”,

and also “have a broad, holistic background”. [1] Meier, Williams and Humphreys [2] state that “the workers of

the 21st century must possess cross-functional inter-disciplinary knowledge, skills, and attitudes, which extend

well beyond the traditional scope of technological training”.

TKK’s Strategy 2015-document claims that one of the ideals of higher education at TKK is “to appreciate

creativity, critical thinking and high-standard expertise” [3]. This will be attained by providing top-level teaching

linked with research. This ideal is, without doubt, related to the current structural transformation of the

information society [see 4, 5] For instance, societies are confronting rapid social and technological changes,

economic and cultural globalization which furthermore have an influence on an individual’s competencies and

maintaining his or hers expertise in working life [6] Engineering is a typical example of a profession performing

symbolic-analytic or knowledge-intensive work. In this type of work, creating and maintaining expertise and

scientific thinking skills is particularly crucial.

2

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND EARLIER RESEARCH

Expertise in general refers to the characteristics, skills, and knowledge that distinguish experts from novices and

less experienced people [7]. One encyclopaedia describes an expert as “someone who has a special skill or

special knowledge of a subject, gained as a result of training or experience” [8]. Expertise has usually been

defined as the ability to successfully execute problem-solving tasks related to one’s professional field [9]. It can

also be related to knowledge which has been researched, for example, at the University of Technology, Denmark

- Ahmed, Hacker & Wallace [10] have studied what the role of knowledge and experience plays in engineering

design. They argue that knowledge and experience play an important role in engineering design. They continue

that “knowledge provides the capacity to make decisions and adopt courses of action”. [10] Combining

theoretical knowledge with practice will lead to a deeper learning and understanding in order to gain in expertise.

In more current research, Ahmed [11] states that competence is related to the level of ability to apply knowledge.

Therefore, an understanding of different levels of expertise is necessary in order to understand competence [11].

Competencies achieved during engineering education and later in working life, can be divided into key technical

and non-technical competencies [12, 2]. Another way of viewing engineering competencies is to divide them

into two distinctive areas – the science of engineering and the practice of engineering. The science of

engineering is the set of mathematical and scientific tools used to solve engineering problems. However, the

practice of engineering may be defined as the recognition and formulation of a problem and its solution. [13].

Davis, Beyerlein & Davis [5] have been researching how an engineer profile is developed. Their results showed

that 50 American engineers in the research group gave high importance to the following engineering attributes:

•

technical competence

•

communication

•

profound thinking

•

solution orientation

•

professionalism, and

•

client orientation.

In their results, continuous learning was ranked lower. The respondent group in this research consisted of both

academic and non-academic engineers. [5]

Mäkinen and Olkinuora [14] have researched academic expertise at Finnish universities. They conclude that

regardless of branch, academic expertise should include IT skills, flexibility, social skills and especially, an

ability to choose the most relevant knowledge from flood of information. Furthermore, they state that the ability

to continuously renew knowledge and skills according to the ideals of lifelong learning is crucial for knowledgeintensive work. Mäkinen and Olkinuora [14] have challenged the question where expertise can be or should be

built up –in higher education or in working life.

According to Kuhn, Amsel & O’Loughlin, scientific thinking can include the notion of logical thinking, problem

solving, induction and inductive thinking skills. It is very unlikely that thinking skills are either entirely general

or entirely domain specific. These writers pose a question whether instruction (in higher education) in thinking

skills can be undertaken in domain-specific or in a more general form [15]. Scientific thinking skills have been

researched to a large extent among children and youth [see 16]. However, students in higher education, in

particular engineering students, have not yet much covered in research.

In this research learning, expertise and scientific thinking form the basic components when studying electrical

engineers’ perceptions. Research related to this field has been done, for example, with graduates from computer

sciences, teacher education, general educational sciences and pharmacy [17], as well as into expertise in software

design [see 18]. Empirical studies on learning, expertise and scientific thinking, focused on electrical engineering

are, however, rare.

3

RESEARCH AIMS

The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions of electrical engineering students on expertise and scientific

thinking. Data were examined from two different viewpoints: 1) whether engineers’ perceptions had a

connection to learning skills and their development, and 2) what kind of aims for engineering education, the

engineering students perceived. Electrical engineers were chosen for, to the sample group of the research

because of my earlier experience as a teacher at the Department of Electrical and Communications. This group

was also chosen because this department has the largest number of students at TKK (approximately 3 000

compared to a total of 15 000 at TKK). Thus, results can represent a rather large share of students and graduates

at TKK.

The first viewpoint emphasizes learning in particular, lifelong learning. Learning to learn can be regarded as a

key competence for engineers, and professionals in every field. The second viewpoint derives from the changing

information society around us, and how electrical engineers perceive themselves as a part of the society and

working life. The second viewpoint includes a notion of the value of the engineering studies – are engineering

studies a means for reaching something, or are they providing students with engineering expertise in general?

4

DATA COLLECTION AND DATA ANALYSIS

4.1

Data collection

The qualitative date for this research was gathered in October-November 2007 with a quantitative Internet

survey. The survey was sent to 626 electrical engineering students, and their addresses were received from TKK

Student registration office. The students in this sample group are delayed in their studies (studied 7 years or more

at TKK), had more than 80 study weeks and were registered in autumn 2007at the Department of Electrical and

Communications Engineering (after TKK’s organizational change on 1st Jan. 2008 the Faculty of Electronics,

Communications and Automation). This sample group was selected because of their current study situation.

Their perceptions on studies and learning may support the development of education at the Faculty of

Electronics, Communications and Automation.

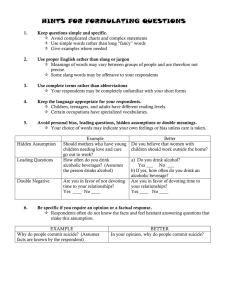

The Internet survey in all consisted of 36 question items, of which two were optional, open-ended metaphor-type

qualitative questions. The metaphor question type was adapted from surveys of the Finnish Association of

Graduate Engineers TEK. The respondents were asked to continue a phrase with as many words or sentences as

possible. The open-end questions to answer were as follows:

4.2

o

Engineering expertise is… Would you please continue this with as many words as possible

o

Scientific thinking is… Would you please continue this with as many words as possible

Description of the respondent group

Altogether 120 respondents completed the Internet survey. The respondent rate of the entire survey was 19, 2 per

cent. 109 respondents of the entire group answered the open-ended qualitative questions. This can be regarded as

a fairly satisfactory return in comparison with the entire sample of respondents, especially when considering that

answering these two questions was optional. Research studies [19] claim that response rates to e-mail surveys

have significantly decreased since 1986. One of the reasons for lower response rates can be the enormous

increase in unsolicited e-mail to Internet users. The response rate to the qualitative questions was 91 per cent.

The average age of the respondent group was 32, 6 years. Thirteen of them were women (12 %), and the rest 96

men (88 %, see Table 1.) This represents well the share of women studying at the Faculty of Electronics,

Communications and Automation. The share of women studying at the entire TKK is approximately 25 per cent.

Description of the respondent group

Gender

Female

Male

Total

Work experience

from 1 to 5 years

from 6 to 9 years

from 10 to 14 years

over 15 years

freq.

%

13

96

109

12

88

100

70

17

11

11

64

16

10

10

TABLE 1. Description of the respondent group

The largest proportion of the respondents had work experience from one to five years (see Table 1) My

preliminary expectation was that this group of students would not be active, full-time students any more, but in

working life. 10 respondents of the total 120 answered that they were full-time students, which supported this

expectation. One of the major reasons for their delayed studies and graduation was going to work and their

financial situation. The survey had one question on graduation plan from TKK. The majority of the respondents

(97 % of 120) replied that they are planning to graduate in a two or three years time.

4.3

Method of analysis

The collected qualitative data - the answers of the respondents - were collected into one document. The collected

data of the two open-end questions consisted of 22 pages of text transformed into Windows Word Table-form

from the original Internet survey file.The data were analysed using a content analysis method. Krippendorf [20]

defines content analysis as “a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts to the

contexts of their use”. Content analysis is one of several qualitative research approaches used in educational and

social sciences. In this research, content analysis is derived from the collected data. It can be regarded as a wide

theoretical framework which is possible to be incorporated within several, different analysis contexts.

The texts were read and examined over and over again, and combining categories were found in them. Most of

the respondents had written at least three or four longer sentences. Quite a few had written a longer chapter.

After having read the body of text several times, it was possible to find categories describing respondents’

perceptions. Three different categories were found based on the collected data. Respondents’ answers were

numbered per each person in the data. Numbers used with quotations in the Research findings section refer to

persons and their perception describing each category. The numbers are combined with a letter “R” referring to a

word respondent.

5

RESEARCH FINDINGS

The data and the results showed that most of the respondents were aware of the demands of the information

society. Furthermore, they were also aware of the requirements for knowledge-intensive work. The majority of

the respondents mentioned information, knowledge, its creation or processing in some ways in their answers.

Referring to the first research aim, learning skills and their development were rarely mentioned. However,

respondents mentioned learning in different forms. Three different categories were found based on the collected

data and content analysis.

The first category can be named as a learning view category. According to the analysed data, this divided

engineering students most. Only a small minority mentioned lifelong learning, continuous learning, or learning

in general as a means for maintaining expertise, competencies or skills. This minority was also able to identify

daily work tasks as a means of learning. However, learning to learn is a key competence for a knowledgeintensive work profile. Even fewer respondents answered that learning could be a common way of learning with

others, for example, sharing new knowledge in working places or in other communities. Some did mention that

engineering expertise is continuous learning. However, the idea of learning was hidden tacitly in their opinions

that studies at TKK were not enough; it was just the beginning, they had to grow gradually into experts at work.

The following examples describe the first category:

“[it is] updating your own skills continuously, that is continuous learning. You have to tackle new

things and ideas with enthusiasm, and study them at least in general level, in order to follow

development” R39

“Engineering expertise at its best is diverse learning, developing and knowledge in a dynamic work

environment. Engineering expertise requires also competencies in business and social skills.” R59

The second category can be named as a status category. There were clearly two types of respondents in this

category: those who saw engineering education and the Master’s degree as a means of achieving something of

merit or benefit in their lives. Several things were named: a better job, better wages, work possibilities abroad

(outside Finland), better chances to achieve a more respected position etc. One respondent even mentioned “a

beautiful wife”. These respondents very seldom mentioned the connection to the first category, the idea of

learning. The other group regarded engineering education as a way to better understand for example the society,

links to other scientific disciplines, colleagues at work, or the work context itself. This group had a more

systemic and holistic approach to engineering expertise. Western society, for example in Scandinavia, can be

regarded as somewhat emphasizing material values of life. This naturally reflects also engineering education

students. Engineering education in Finland is, to some extent, renowned as promising a good, well paid career

with high status. Persons in the other group mentioned that engineering expertise as very important or essential

for the whole society. This category is to a certain extent related to the areas which Martin et al. [13] has

presented (the science and practice of engineering). Here there are two examples of this category as follows.

The first one describes the answers of those with more materialistic values and the second the latter part.

“A significant professional skill which is less appreciated in Finland compared to other European

countries. Engineering expertise is an important factor when filling up work positions” R62

“Has to be based on a wide outlook of own branch before you can go deeper into the details of your

own field of expertise. You must be able to see connections between different things, also outside the

technical field” R55

The third category divides the respondents also into two smaller groups. It is named as an individual/collective

category. This category has links to the two earlier described categories. Its name relates to how the respondent

sees the connection to his/her surroundings or context. In this category those having a collective perception, can

see links in both asked questions to their colleagues, clients, work environment, and society in general. Some of

these respondents mentioned in their answers that expertise is knowledge sharing, or it can be an ability to

communicate with others and guide them. Those respondents, who had a somewhat materialistic way of seeing

expertise and scientific thinking, may be categorized in the individual category. The following quotations

represent this category from both viewpoints. The first one is an example of a collective thinking category:

“[it is] using knowledge and competencies in your daily work. It is ability to analytical problem solving

with others.” R44

The following quotation describes the individual thinking category:

“Essential for making a good career. According to my opinion the best way to become an expert is to

focus an interesting field so that you control it really well. Besides, becoming an expert requires

continuous interest towards your chosen field, and you must be able to update knowledge to keep up

with the current development.” R75

Additionally, a small part of the respondents belonged to a “critical” group according to their answers. However,

a fourth category was not formed from them because the share of the respondents was rather small. These

respondents had critical attitudes to the both questions about the studies at the Faculty of Electronics,

Communications and Automation. In particular, the answers to “Scientific thinking is...” included much criticism

of the curricula and teaching of the faculty. According to their perceptions, scientific thinking could not be

developed at TKK, or during their studies at TKK. Some of the respondents mentioned other courses at other

departments/faculties at TKK in which there were better possibilities to learn some basics of it. Most of the

respondents in the entire sample group had the idea that scientific thinking skills are something not needed in

daily working life, but just by with researchers in scientific field. Only few people had answered that creating

scientific thinking skills is one aim of higher education.

The majority of the respondents mentioned the following competencies or abilities belonging to engineering

expertise and scientific thinking. Many of them were mentioned as answers to the both questions:

•

Analytical thinking

•

Problem solving skills

•

Critical thinking skills

•

Ability to search information and create new information

•

Seeing links between different fields of expertise, and even outside technical field

•

Integrating theories into practice

Age and the length of work experience did not have much effect on answers, or on forming different categories.

A rather young respondent (from 26 to 29 years old) could have wider, holistic perceptions on society, or e.g.

‘developing your expertise’. However, middle-aged respondents (over 40 years) did not all belong to the group

with many years of work experience. It may be that this sample group with the delayed studies is rather

heterogenic, and further research would be needed in order to go deeper into factors affecting their perceptions

and thinking.

6

CONCLUSIONS

This research aimed to understand the perceptions of electrical engineering students. The majority of the

respondents were in working life, and trying to complete delayed studies at the Faculty of Electronics,

Communications and Automation. Their answers on expertise and scientific thinking were analysed with a

content analysis research approach. Three categories were found, and the categories had links with each other.

When examining the research aims, the first aim was partly achieved. The connection between the perceptions of

engineering expertise and learning was found, but not very widely. Learning skills and their development were

rarely named. The second category of status-oriented perceptions showed that individuals could see their own

situation and career development. However, a smaller number of respondents mentioned links with the

surrounding society (colleagues, clients, other branches and fields in and outside engineering).

The majority of the respondents had mentioned several engineering attributes in common in their answers. One

respondent wrote that engineering expertise is “a common way of thinking with other engineers” (R79) Despite

the categories found and differences in their answers, majority of the respondents in the sample group shared this

way of “engineering” thinking, and also shared the idea of “engineering identity”. However, not enough

attention has been paid to lifelong learning in engineering, and in particular how engineers reflect on their

learning skills. Thus, more research on this subject is needed.

References

[1] Bordogna, J. (1997) Making Connections: The Role of Engineers and Engineering Education. The Bridge

27(1). Available online at: http://www.nae.edu/nae/bridgecom.nsf/weblinks/NAEW-4NHMPY?OpenDocument

[2] Meier, R.L., Williams, M.R. & Humphreys, M.A. (2000). Refocusing Our Efforts: Assessing Non-Technical

Competency Gaps. Journal of Engineering Education, July 2000, 377-385.

[3] http://www.tkk.fi/en/about_tkk/strategies/index.html

[4] Castells, M., Flecha, R., Freire, P., Giroux, H.A., Macedo, D. & Willis, P. (eds.) 1999. Critical Education in

the New Information Age. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

[5] Davis, D.C., Beyerlein, S.W., & Davis, I.T. (2005) Development and Use of an Engineer Profile.

Proceedings of the 2005 American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition.

[6] Rychen, D.S. (2002) Key Competencies for the Knowledge Society. A Contribution from OECD Project

Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo). Education – Lifelong learning and the Knowledge

Economy, Conference in Stuttgart, October 10-11, 2002.

[7] Ericsson, K.A. (2006) An Introduction to Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance: Its

Development, Organization, and Content. In Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance (eds.

Ericsson, K.A. et al.) Cambridge University Press

[8] Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, (2006). Harlow, UK: Pearson Longman

[9] Ropo, E. (2004) Teaching Expertise. Empirical findings on expert teachers and teacher development. In

Professional Learning: Gaps and Transitions on the Way from Novice to Expert (Eds. Boshuizen, H.P.A.,

Bromme, R. & Gruber, H.) Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht.

[10] Ahmed, S., Hacker, P. & Wallace, K. (2005) The role of knowledge and experience in engineering design.

International Conference on Engineering Design ICED 05 Melbourne, August 15-18 (2005).

[11] Ahmed, S. (2007) An Industrial Case Study: Identification of Competencies of Design Engineers. Journal of

Mechanical Design, July 2007, vol. 129, pp. 709-716.

[12] Evans, D.L., Beakley, G.C., Couch, P.E. & Yamaguchi, G.T. (1993) Attributes of Engineering Graduates

and Their Impact on Curriculum Design. Journal of Engineering Education, October 1993, 82(4), 203-211.

[13] Martin, R., Maytham, B., Case, J. & Fraser, D. (2005). Engineering graduates’ perceptions of how well they

were prepared for work in industry. European Journal of Engineering Education, May 2005, 30(2), 167-180.

[14] Mäkinen, J. & Olkinuora, E. (1999) Building academic expertise in information society – who demands and

what? (Akateemisen asiantuntemuksen rakentaminen tietoyhteiskunnassa – kuka vaatii ja mitä? Kasvatus 30 (3),

pp. 290-305.

[15] Kuhn, D., Amsel, E. & O’Loughlin, M. (1988) The Development of Scientific Thinking Skills.

Developmental Psychology Series. Academic Press, Inc.

[16] Kuhn, D. & Pearsall, S. (2000) Developmental Origins of Scientific Thinking. Journal of Cognition and

Development, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 113-129.

[17] Tynjälä, P., Slotte, V., Nieminen, J., Lonka, K. & Olkinuora, E. (2006) From University to Working Life:

Graduates’ Workplace Skills in Practice. In Higher Education and Working Life. Collaborations, Confrontations

and Challenges (Eds. Tynjälä, P., Välimaa, J. & Boulton-Lewis, G.) Elsevier: Amsterdam.

[18]Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C. & Volmer, J (2006) Expertise in Software Design. In Cambridge Handbook of

Expertise and Expert Performance (eds. Ericsson, K.A. et al.) Cambridge University Press

[19] Sheehan, K.B (2001) E-mail Survey Response Rates: A Review. Journal of Computer-Mediated

Communication, 6 (2), 0-0 doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00117.x

[20] Krippendorf, K. (2004) Content Analysis: Introduction to Its Methodology. 2nd ed. Sage Publications:

Thousand Oaks, USA.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research is funded by the Faculty of Electronics, Communications and Automation at Helsinki University of

Technology TKK and the Lifelong Learning Institute Dipoli.