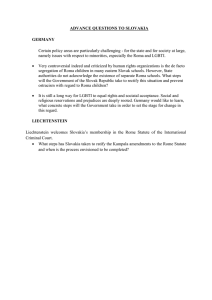

Nothing About Us Without Us? - European Roma Rights Centre

advertisement