Persistent Segregation of Roma in the Czech Education System 2008

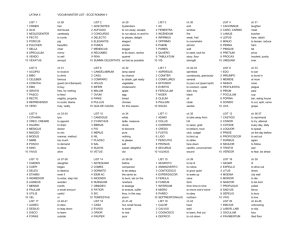

advertisement