Castles, Confusion, and the Count

advertisement

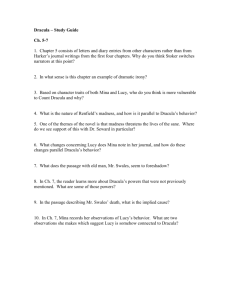

Proceedings of The National Conference On Undergraduate Research (NCUR) 2012 Weber State University, Ogden Utah March 29 – 31, 2012 Castles, Confusion, and the Count: Vlad the Impaler’s Impact on Tourism in Romania Rachel Lawrence Department of History The University of Evansville 1800 Lincoln Avenue Evansville, Indiana 47722 USA Faculty Advisor: Dr. Annette Parks Abstract Vlad the Impaler is often buried in the vampire myths of Count Dracula, even in Romania where the Impaler lived and died. His castles are forgotten, while those stolen by Bram Stoker and Hollywood reap the benefits of a shadow of association. Despite this, Romania capitalizes on Vlad’s image, and blends it with the vampire to create a booming tourist industry. If this continues, Vlad the Impaler, who is identified as a Romanian national hero, will be lost in the image of something far worse, and Romania will lose its hero to a myth. Vlad the Impaler (1431-1476) was the inspiration for Bram Stoker’s Count Dracula, and the Impaler’s family name was in fact Dracula. Stoker adopted the name for his blood-sucking Count, and now the two seem interchangeable. Castle Bran is called Dracula’s Castle, but little evidence suggests that Vlad was ever there. Vlad the Impaler’s castle is largely unknown, yet has a completely different history and exemplifies the Impaler’s drive for order and defense, and also supports his position as a national hero. A Dracula Land theme park in 2001 was supposedly going to mix the Count and the Prince, making it educational yet interesting, and making resources available for both the Count and the Impaler. Finally, the Impaler’s lost grave, and corpse, has not helped the vampire myth. These aspects of the Prince-Count confusion require analysis in order to separate the two. By examining two castles, a failed theme park, and the alleged grave of the Impaler, the Prince and the Count can be distinguished, the Impaler’s national-hero status can be evaluated, and potential impacts on Romanian tourism can be explored. Keywords: Romania, Dracula, Tourism 1. Introduction Vlad the Impaler, who lived from 1431-1476, ruled a tiny principality called Wallachia. He was a bloodthirsty tyrant and murdered 100,000 people, at least 40,000 of whom he impaled, while defending his country and throne.1 His family name was Dracula, the name adopted by Bram Stoker for his famous count. Dracula tourism in Romania has exploded in recent years, and with it came a smearing of the lines between Count Dracula and Prince Vlad. Romania capitalizes on Vlad’s image, blending it with Count Dracula to drive a booming tourist industry, and now the two seem interchangeable. Western vampire myths have buried Vlad Dracula. Tourists frequently confuse Vlad’s castle, the real Castle Dracula, for one owned by his enemies, Castle Bran. Romanians fought among themselves over a Dracula Land theme park that would have merged the Count and the Prince yet again for an interesting yet supposedly educational tourist destination. Finally, the Impaler’s lost grave only fuels the vampire myth. By examining the two castles, a failed theme park, and the alleged grave of Dracula, I will distinguish the Prince from the Count, evaluate Vlad’s national-hero status, and explore the future of Romanian tourism. 2. The Real Dracula Vlad Dracula was a prince who ruled Wallachia from 1456 to 1462, and briefly in 1476 before the Turks assassinated him.2 Over his short reign, he acquired his nickname, Impaler, through his favorite method of execution. He also diminished the power of the nobility and centralized the corrupt and violent government of Wallachia for the first time by confiscating the land and wealth of the nobles he murdered3, and he raised Wallachia socially by eliminating beggars and those infected with disease. In a story known as the “Burning of the Poor,” Vlad summoned all beggars in his land, approximately two hundred according to contemporary sources, and offered them a feast with princely wine and food. As the beggars gorged themselves and drank more and more, Vlad set the hall on fire to kill those inside.4 With the poorest people and disease-ridden vagrants eradicated, Vlad could socially raise his country. He spent four years of his reign waging a war against the German Saxons of Transylvania over political problems that started in Hungary, yet to which Vlad was personally tied through alliances and rivals.5 In addition, he took on, with no help from Europe, the Ottoman Turks, and with a poorly trained army one-third the size of the sultan’s, Vlad won. He staged the “Night Attack,” during which he took 8,000 cavalry and attacked the Turkish camp in the middle of the night with the mission of killing the sultan in his sleep. When that failed, Vlad returned to his capital, where he created a scene forever-known as the Forest of the Impaled. The Forest comprised of 20,000 Turkish prisoners and Wallachian men, women, and children, all impaled, and the sight of it sent the Turks into a frantic retreat. His war with the Turks, even to his enemies, was deemed Vlad’s “finest hour.”6 Vlad gave the Wallachians back their country by keeping out the Turks and even the Hungarians through two wars. Scholars across the world have excused Vlad and his vicious methods as “he was a man of his time” and “Machiavellian.” These explanations are much too simple. He was not merely a man of his time, but more complex. Now, however, he is portrayed in Romania and across the world as a hybridization of the black-caped, fanged, seductive Victorian Count Dracula and the heroic yet bloodthirsty prince. 3. Castle Bran In the 1890’s, Bram Stoker’s research for his vampire novel took him to the British Library where he discovered a manuscript that forever altered Vlad the Impaler’s legacy. A German pamphlet printed in 1491 mentioned the name “Dracula,” describing him as a bloodthirsty madman. Stoker renamed his title character.7 He placed the home of this “madman called Dracula” in the Borgo Pass, and modeled the Count’s castle on Castle Bran. Despite being over two hundred miles from the Borgo Pass, Castle Bran has become Castle Dracula.8 Five hundred thousand tourists visit Castle Bran each year. Because of its imposing presence, Bran has been used in Dracula and other horror films.9 First documented in 1377, Bran served to protect the trade center of Braşov to the north.10 Bran occupies the top of a solid rock, two hundred feet above a small village.11 The castle contained guns, watch towers, and secret passages, but no “crypt,” to the dismay of Dracula enthusiasts.12 The Gothic chapel drives home the “Dracula” look to the place, and the secret passages led to torture chambers and escape routes, which Vlad the Impaler used in his own castle.13 Confiscated by Communists in 1948, Castle Bran returned to the Hapsburg family in 2006. The Hapsburgs offered to sell it for $135 million, but the Romanian Ministry of Tourism accused them of trying to profit from this “national treasure.” The family worried that new owners would use it as the centerpiece of a “tacky theme park.”14 Braşov County now runs the castle as a museum honoring the family and Bran’s history, with little reference to the Impaler. “We want the castle to represent all that is good and was good about the country,” reported Archduke Dominic Hapsburg. The castle was given to Queen Marie in 1920 for her help in unifying Romania in 1918. She so loved Bran that she requested her heart be buried in it, and her request was honored.15 Bran’s locals are almost completely dependent on tourism, and offer bed-and-breakfasts and Dracula merchandise. 16 Little evidence suggests Vlad ever visited Bran, although he marched past it on his way to burn Braşov in 1459, during his war with the German Saxons of Transylvania.17 However, Bran is marketed as “Dracula’s Castle,” even to Romanians. The castle is Romania’s top tourist draw. 122 4. Castle Dracula The real Castle Dracula is a stark contrast. It is rarely visited, and relatively unknown even to Romanians, although it is receiving more attention. It is incredibly difficult to reach, and one must climb 1,480 steps to cross a bridge over a deep rift in the mountain to get to the castle. Vlad’s “eagle’s nest” sits 1,000 feet in the air. Welcoming the visitor are stocks, an axe on a block, an impaled mannequin, and another stake at the ready, all of which are covered in fake blood, with the Romanian flag flying above on the main tower.18 Local peasants give visitors Bibles and crosses, still tell stories of the Impaler, and rarely speak of the castle.19 They call it an evil place, warning visitors of the “curse of Dracula” on the treasure rumored to be still buried in the castle’s vaults.20 Castle Dracula has a single guard and overlooks a power plant and a hotel called Dracula Inn.21 In his quest to subdue the scheming nobles, Vlad forced them to build Castle Dracula. He discovered that they murdered his father and older brother, and they would not hesitate to do the same to him to preserve their power. During the Easter celebrations of 1457, Vlad chained the nobles together and immediately impaled the oldest ones and their families, numbering around five hundred. He force-marched the remaining five hundred nobles and their families about ninety miles north from the capital, Tîrgovişte, to the citadel where he wished his mountain fortress to be. An untold number of nobles fell to their deaths from the mountain, died from hunger, or by Vlad’s hand, during the construction. Castle Dracula became Vlad’s retreat, and he was able to watch for brewing trouble in Transylvania and Wallachia from his new fortress in the Transylvanian Alps.22 He established his dominance over the nobles, becoming a hero to the lower classes by doing so, and Castle Dracula is a tainted monument to his achievement. 5. Dracula Land Theme Park Much worse than a misidentification was the Dracula Land theme park, proposed in 2001. The masterminds of this project intended to combine the prince and the count, to honor the “image of a great Romanian hero,” said Dan Agathon, then Director of the Ministry of Tourism. This $60 million project included an educational Institute of Vampirology, a replica of Stoker’s Castle Dracula, catacombs, labyrinths, an artificial lake, and a massive hotel with Dracula-themed roller coasters and sundry foods such as “blood pudding,” a “dish of brains,” and garlic ice cream.23 The idea was to allow the public to learn about both Prince Vlad and Count Dracula. The park was to be in Sighişoara, the best preserved medieval town in Romania. The idea of this park created uproar among the citizens, mostly over “cultural sustainability.” They deemed the park “profit-seeking, gaudy entertainment” that would replace the medieval character of the town, endangering Sighişoara’s cultural identity. Vlad the Impaler was born in the town, and installing a hybrid figure in the theme park would only distort Vlad’s image further. Vlad was to be “embellished” and turned into a vampire, but merchants already combined Vlad and the Count in their merchandise. Other opposition came from the religious sector. Sighişoarans feared that devil worshippers and vampire cults would infiltrate the town, degrading Christian values.24 Vlad was a fanatic Orthodox Christian25, and this vampire park certainly flew in the face of his historical image. The government tried to appeal to the historical and touristic aspect of Dracula and his fans, yet nothing in the park related to Vlad as a person. It was ultimately a failure for the Ministry of Tourism. Apart from cultural degradation, many feared the economic impact of Dracula Land. Cost of living would increase and the town would come to depend on tourism.26 The 3,000 jobs the park would create would only be temporary, and 37,000 Sighişoarans needed jobs. Romanians were offended by Stoker’s theft of their hero and Vlad’s “rebirth” as a vampire, and many believed the park would further confuse tourists, but they needed money.27 With new money they could restore their crumbling medieval walls.28 This conflict eventually pushed plans to Snagov, near Bucharest, but the project was postponed indefinitely in 2003, and cancelled officially in 2006.29 6. Snagov Monastery Snagov Monastery is on an island in the middle of the deepest lake in Romania. Although built by his predecessor, this was Vlad’s favorite monastery. He fortified the island, taking thick walls to the lake’s edge, adding towers and torture chambers, and murdering many political enemies here.30 He was supposedly buried at Snagov near the main altar in 1476, after he was decapitated in battle against the Turks. Legend has it that shortly after his interment, a 123 horrendous storm with hurricane winds demolished one of two chapels, and scattered parts into the lake. Supposedly, the bell can still be heard today beneath the water.31 In 1931, archaeologists removed the altar stone, but the mighty Impaler’s grave was empty. Near the door, however, was another grave. Five centuries of passing feet had erased the inscription, but the grave contained a rotted coffin covered by a purple cloth. Inside the coffin was a headless skeleton wearing a yellow robe with red sleeves, and the remains of a crown lay next to the body, along with various other artifacts.32 Since Vlad belonged to a chivalric Order of the Dragon, whose costume matched that of the skeleton, the excavators believed the door grave belonged to the Impaler, and perhaps the monks moved his body after his burial to protect it.33 Everything was removed from the tomb and taken to the National Museum of History in Bucharest, and disappeared.34 The road in Snagov that leads to the monastery is called Monastirea Vlad łepeş, the monastery of Vlad the Impaler. Inside is an excellent display of the monastery’s history and highlights of Vlad’s life, supplemented by tours given by the monks, and Vlad’s grave near the altar is decorated with a chalice, fresh flowers, his picture, and a candle.35 7. National Hero? The Impaler’s national hero image in Romania is as complex as his life. Romanians seem to be more drawn to Michael the Brave and Stefan the Great, also identified alongside Vlad as national heroes. Vlad is promoted at sites associated with him, of course, but fewer streets are named for him than the others. In the nineteenth century, Romania sought to break free of Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman clutches, and they needed heroes, so they looked to the medieval period.36 Many poets called to Vlad in their poetry to save them from economic and political destruction. Poets and historians praised his military exploits and repulsion of the Turks in 1462.37 During the Communist period, Vlad achieved national hero status. His popularity peaked in 1976, the 500th anniversary of his death, for maintaining Wallachian independence, for which Vlad is called the father of Romanian sovereignty.38 Communist dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu erected statues and busts of Vlad throughout Romania, yet none in Bucharest, the city Vlad founded in 1459. More streets in Bucharest were named after Stefan and Michael than Vlad.39 Communist officials banned books and films about Count Dracula, but promoted Vlad Dracula. The government believed the West unfairly portrayed the Romanian hero as an unholy bloodsucker.40 Vlad served as a model for government, and “Impalement Day” parades were held on numerous occasions.41 He is not as prominent as he was in the 1970’s, but is still without a doubt an important figure. Romania seemingly has a love-hate relationship with Vlad: they hold him on an obscured pedestal, as if they are unsure of what to do with him. They hail him for his fight for independence and his achievements, but perhaps are embarrassed by his bloody methods. In Romanian tourism, Prince Dracula is traded for Count Dracula, history traded for money. His connection with Stoker’s count, merely by name, was a gold mine, and Romania still struggles to justify using their hero.42 Their “hero prince” was “spinning gore into gold.”43 It is a finely balanced presentation of history and attraction—the man who murdered 100,000 people and a seductive vampire count. Dracula merchandise first appeared in Romania in the 1970’s after a biography of the Impaler was published by Dr. Radu Florescu and Dr. Raymond McNally.44 Since then, vampire tourism has increased exponentially. Much of the merchandise is gory, dark, morbid, and “vampiric” rather than historical, and is sold everywhere. 45 Vlad’s legacy will not be dismantled in the near future, and some scholars believe that “curious travelers are unlikely to destroy the legacy of a time-tested figure like Vlad.”46 Romanians welcome the tourist dollar, and Count Dracula brings more prosperity than Prince Vlad. While many Romanians feel that Count Dracula is an insult to Vlad, their hero, they continue using him for money. A Dracula-themed strip club in Bucharest was deemed by one author the “prostitution of Romania’s heritage to capitalist exploitation.”47 Peasants see Vlad as a heroic, almost mythical figure, and regard him with respect and affection.48 Romanians realize they cannot escape Dracula or Vlad, and many of them also realize the potential of his myth for tourism.49 They promote the vampire Count, and understandably so, as Romania is one of the poorer countries in Europe. Interestingly, Romania was one of the last countries to hear about Count Dracula. Nicolae Ceauşescu banned the books and the films, so before 1989, most Romanians had never heard of the vampire count.50 Within eleven months of Ceauşescu’s execution, Dracula was published in Romanian, yet the book disappointed Romanians, and even today remains largely unread.51 Nevertheless, Dracula, in either form, drives the country’s tourism. The perception of Vlad as Count Dracula is a problem because Stoker erased Vlad’s accomplishments. During the six years he ruled, Vlad repulsed the Turks, centralized the government, and socially raised Wallachia, and Stoker bypasses all of that, using Vlad’s bloodlust and reputation. Vlad is overshadowed by a seductive, Victorian vampire, the embodiment of fear and death, and that is where our focus lies. We focus on the vampire, not the 124 achievements of the icon. Therein lays the problem. However, Vlad’s methodology is potentially unsettling. He did, after all, viciously murder 100,000 people, so that piece of information creates tension even today. Is Vlad really a national hero? Should he be? The focus on Count Dracula rather than Prince Vlad waves away controversy that might otherwise make Romanians uncomfortable. Vlad’s question is open to debate—he murdered 100,000 people, yet what he did in exchange must be discussed as well. We need to talk about this—should we look at the 100,000 or look at what his results were? This fight over the legacy of Vlad tells us that, the memory of Vlad is altered by Western influences and Count Dracula, and that Vlad’s popularity, because of Bram Stoker, brings prosperity to a poorer country. This theft of heritage, culture, and history, therefore, is the disappearance of truth and memory, or at least the alteration of a memory. What is put forth is an amalgam of Vlad and vampires, a compromise between fact and fiction. Vlad should still be considered a national hero because of his accomplishments. These potentially bring up further questions—how can Vlad help with current issues, such as poverty, centralized states, and ethnic and religious conflicts? We need to know who the real Vlad was in order to understand these other important, ethical, modern questions, such as ethnic and religious conflict between the Gypsies, Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and Muslims in Romania today. He was on the border between Europe and the Ottomans, and he pushed the Ottomans out, he kept them away from Europe. His war in 1462 was successful—he fought back and won, and he did it alone, but all the while he was fighting with his nobles and even waging a religious battle. Maybe Vlad’s story is not so small-scale. He touched Wallachia, certainly, but he touched everybody with the advent of Stoker’s Count, and I believe he also touched Europe in his own time. With Count Dracula, we miss the history and the tensions of the region. If we choose to ignore Vlad’s historical significance and just focus on Count Dracula, we lose context, and we lose the story. In fact, we lose Vlad’s story and the history of the region through the fictionalization of history. Perhaps, in Romania today, Vlad suffers an identity crisis. Romania precariously balances him between national hero and ruthless madman. Perhaps this indicates a struggle for identity in Romania. Should they promote a ruthless madman as a national hero, or should they move past that, deem him a man of his time, and admire him for what he did? These are debatable questions, but in order to find the answer, we must look to who Vlad Dracula really was. We must uncover the true history, get past this shroud of vampirism, and discuss the differences in the portrayal of a so-called national hero. 8. Conclusion I stated earlier that Vlad’s portrayal is a hybridization of the Count and the Prince. This is a problem because the true story of Vlad the Impaler is lost in the quest, and dire need, for money. If we continue to promote the vampire side of Dracula, we will lose Vlad’s story, we will lose the context of his heroism and his viciousness, and lose understanding about the tumultuous history of Romania. Over the course of a six-year reign, Vlad the Impaler brutally murdered thousands, and now he is considered a national icon and has become a tourist attraction. His impact on tourism has greatly improved Romania’s standing in the world market, yet tourism has reduced him to a fictitious monster, and that will not change any time soon. Vampire myths of Count Dracula have consumed, and fictionalized, this real-life national hero. A castle that belonged to Vlad’s enemies, Castle Bran, is mistaken for his because it was given to Bram Stoker’s count. Vlad’s real castle, Castle Dracula, is barely known, and displays Vlad’s bloody reputation beneath a Romanian flag. Although Stoker borrowed Castle Bran for his count’s castle, his notes are unclear as to whether or not he knew of the real Castle Dracula. A Dracula Land theme park would have only further entangled the prince and count, further obscuring the real Dracula. The theme park would have helped the vampire myth because nothing referred to Vlad the Impaler, but focused solely on Count Dracula. The jealously guarded plans indicate that Minister Agathon cared more for profit than for cultural awareness. The park would have brought people and money, but not truth, not an honest discussion of Vlad’s legacy. Even Vlad’s grave at Snagov cannot escape the vampire twist, as his body is missing, yet even today, visitors leave offerings at his altar grave. The legacy and the legend of the mighty Impaler Prince are gold mines for tourism, yet Romania’s culture is at stake. With the promotion of the vampire-prince hybrid, they risk losing one of their most valiant, and controversial, leaders through the distortion of the Prince’s image. Few people have heard of Vlad Dracula, but everyone has heard of Count Dracula. This struggle between the legacy of Vlad reveals an age-old dispute between history, memory, and truth on one hand, and profit on the other. Just as the fictional Pocahontas and the real Pocahontas in the United States, Vlad’s history is capitalized upon for commercial and economic purposes—he provides profit. Romanians still hesitate to use their national icon, yet the 125 money his image and popularity provides is a driving force behind the Romanian economy, and this is a problem. Although Vlad’s popularity is unlikely to fade, his image becomes distorted and suffocated by his vampire counterpart, even though Vlad’s story is “ten thousand times stranger and more terrifying than any fiction.”52 9. Acknowledgments I wish to express my appreciation to Mr. J. Linzy, whose generous donation allowed for this research in Romania. Secondly, I would like to thank Dr. Annette Parks, Dr. Alan Kaiser, and Dr. Michelle Blake for their unwavering patience, energy, and suggestions throughout this project. 10. References Alb, Simeon, email message to author, November 19, 2010. Baddeley, Gavin and Paul Woods, Vlad the Impaler: Son of the Devil, Hero of the People. Kent: Ian Allan Publishing, 2010. Beavis, Samira, “Dracula Land Plans Kept in Dark.” April 4, 2001. Accessed November 19, 2010. http://abcnews.go.com/International/story?id=81304&page=1. “Bran Castle—Restitution Complete.” Accessed October 22, 2010. http://www.roconsulboston.com/Pages/InfoPages/Culture/BranCastle/Restitution.html. Browne, Malcolm, “Dracula’s Bones Mislaid in Rumania.” New York Times, July 27, 1974. Cooper, Aaron, “Staking out Dracula’s Castle in Romania,” October 31, 2010. Accessed November 19, 2010. http://www.cnn.com/2010/TRAVEL/10/30/romania.dracula.castle/index.html?iref=allsearch. Darnton, John, “Count Dracula as Early Rumanian Freedom Fighter.” New York Times, December 16, 1979. De Vries, Lloyd, “Dracula’s Castle Up for Sale,” January 10, 2007. Accessed October 22, 2010. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/01/10/business/realestate/main2345757.shtml. “‘Dracula’s Castle’ Up for Sale in Transylvania,” July 2, 2007. Accessed November 19, 2010. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,287725,00.html. Florescu, Radu and Raymond McNally, Dracula, a Biography of Vlad the Impaler, 1431-1476. New York: Hawthorne Books, 1973. Florescu, Radu and Raymond McNally, Dracula Prince of Many Faces: His Life and His Times. New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 1989. Goldschlager, Seth, “There Was a Real Dracula and He Was Not a Good Old Boy.” New York Times, August 24, 1972. Huggler, Justin, “Dracula Land Theme Park Bites the Dust.” June 29, 2002. Accessed October 22, 2010. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/draculaland-theme-park-bites-the-dust-646699.html. Jamal, Tazim and Aniela Tanase, “Impacts and Conflicts Surrounding Dracula Park, Romania: The Role of Sustainable Tourism Principles.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 13 (2005): 440-455. Kim, Lucian, “Can ‘Dracula Land’ Put Transylvania in the Black?” October 31, 2001. Accessed November 18, 2010. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/10/1031_wiredracular2.html. 126 Light, Duncan, “The Status of Vlad łepeş in Communist Romania, a Reassessment.” Journal of Dracula Studies 9 (2007): 1-14. Light, Duncan, “When Was Dracula Translated into Romanian?” Journal of Dracula Studies 11 (2009): 1-8. Luxmoore, Jonathan. “Cancellation of Dracula Park Hailed as Victory by Romanian Church.” Ecumenical News International, April 6, 2006. Accessed February 18, 2012. http://www.eni.ch/articles/display.shtml?06-0305. McNally, Raymond, and Radu Florescu, In Search of Dracula: the History of Dracula and Vampires, Completely Revised. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1994. Miller, Elizabeth, Reflections on Dracula: Ten Essays. White Rock: Transylvania Press, 1997. Moore, Ede Piers, “Dracula Lives, but His Theme Park Sucks.” The Environmental Magazine, (September-October 2002), 1. Pinto, Barbara, “Dracula’s Castle Goes Up for Sale.” January 9, 2007, Accessed November 19, 2010/ http://abcnews.go.com/Travel/story?id=2782064&page=1. Rezachevici, Constantin, “The Tomb of Vlad łepeş: the Most Probable Hypothesis.” Journal of Dracula Studies, 4 (2002): 1-8. “Romania Builds Dracula Land.” March 22, 2001, Accessed October 22, 2010. http://www.news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe.1234648.stm. “Romania to Build Dracula Theme Park.” July 8, 2001. Accessed November 3, 2010. http://articles.cnn.com/2001 07-08/world/transylvania_1_sighisoara-theme-park-dracula.html. Salabasev, Eugeniu, “Former Royal Family Selling ‘Dracula’s Castle.’” Updated July 2, 2007. Accessed October 22, 2010. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/19563707/ Spörer, Hans. “Dracole Waida.” 1491. Currently at the Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. Travers, Ben, “Vlad the Unique Selling Point.” January 6, 2007. Accessed October 22, 2010. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/property/overseasproperty/3355514/Vlad-the-unique-selling-point.html. Trow, M.J., Vlad the Impaler: in Search of Dracula. Gloucester: Sutton Publishing, 2003. Vorsino, Michael, “The Dragon, the Raven, and the Ring.’ Journal of Dracula Studies 5 (2003), 1-4. Wagner, Peter. “Dracole Waida.” 1488. Currently at the Rosenbach Museum and Library, Philadelphia. Wright, David, “A House Tour of Dracula’s Castle.” ABC News, March 11, 2007. Accessed 22 October 2010. http://abcnews.go.com/WNT/International/story?id=2942213&page=1. 11. Endnotes 1 Radu Florescu and Raymond McNally, Dracula Prince of Many Faces: His Life and His Times, (New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 1989), 104. 2 Florescu and McNally, Prince of Many Faces, 81. 3 Florescu and McNally, Prince of Many Faces, 107. 4 Peter Wagner, Dracole Waida, Nürnberg, 1488, Item 20. 5 Florescu and McNally, Prince of Many Faces, 114-121. 127 6 Florescu and McNally, Prince of Many Faces, 148 & Gavin Baddeley and Paul Woods, Vlad the Impaler: Son of the Devil, Hero of the People, (Kent: Ian Allan Publishing, 2010), 224. 7 Seth, Goldschlager, “There Was a Real Dracula and He Was Not a Good Old Boy,” New York Times, August 24, 1972, 9 & Hans Spörer, Dracole Waida, Bamberg, 1491. 8 Tazim Jamal and Aniela Tanase, “Impacts and Conflicts Surrounding Dracula Park, Romania: The Role of Sustainable Tourism Principles,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 13 (2005): 449. 9 Eugeniu, Salabasev, “Former Royal Family Selling ‘Dracula’s Castle,’” accessed October 22, 2010, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/19563707/ & “‘Dracula’s Castle’ Up for Sale in Transylvania,” accessed November 19, 2010, http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,287725,00.html. 10 “Bran Castle—Restitution Complete,” accessed October 22, 2010, http://www.roconsulboston.com/Pages/InfoPages/Culture/BranCastle/Restitution.html, 1. 11 Ben Travers, “Vlad the Unique Selling Point,” January 6, 2007, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/property/overseasproperty/3355514/Vlad-the-unique-selling-point.html. 12 Raymond McNally and Radu Florescu, In Search of Dracula: the History of Dracula and Vampires, Completely Revised, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1994), 61 & David Wright, “A House Tour of Dracula’s Castle,” ABC News, March 11, 2007. http://abcnews.go.com/WNT/International/story?id=2942213&page=1, 1. 13 Radu Florescu and Raymond McNally, Dracula, a Biography of Vlad the Impaler, 1431-1476, (New York: Hawthorne Books, 1973), 86. 14 Wright, “A House Tour of Dracula’s Castle,” 1. 15 Lloyd De Vries, “Dracula’s Castle Up for Sale,” January 10, 2007, http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/01/10/business/realestate/main2345757.shtml, 1 & “Bran Castle—Restitution Complete,” 1. 16 Barbara Pinto, “Dracula’s Castle Goes Up for Sale,” January 9, 2007, http://abcnews.go.com/Travel/story?id=2782064&page=1, 1 & de Vries, “Dracula’s Castle Up for Sale,” 1. 17 Aaron Cooper, “Staking out Dracula’s Castle in Romania,” October 31, 2010, http://www.cnn.com/2010/TRAVEL/10/30/romania.dracula.castle/index.html?iref=allsearch, 1; M.J. Trow, Vlad the Impaler: in Search of Dracula, (Gloucester: Sutton Publishing, 2003), 169. 18 Personal research trip to Castle Dracula, July 2011. 19 McNally and Florescu, In Search of Dracula, 73-74. 20 Florescu and McNally, Prince of Many Faces, 93-94. 21 Personal research trip to Castle Dracula, July 2011. 22 Florescu and McNally, Prince of Many Faces, 91-93. 23 “Romania Builds Dracula Land,” March 22, 2001, http://www.news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe.1234648.stm, 1 & Jamal and Tanase, “Impacts and Conflicts Surrounding Dracula Park, Romania,” 5 & Ede Piers Moore, “Dracula Lives, but His Theme Park Sucks,” The Environmental Magazine, September-October (2002), 1. 24 Jamal and Tanase, “Impacts and Conflicts Surrounding Dracula Park, Romania,” 5-7. 25 Florescu and McNally, Prince of Many Faces, 97. 26 Jamal and Tanase, “Impacts and Conflicts Surrounding Dracula Park, Romania,” 5. 27 Justin Huggler, “Dracula Land Theme Park Bites the Dust,” June 29, 2002, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/draculaland-theme-park-bites-the-dust-646699.html, 1. 28 Lucian Kim, “Can ‘Dracula Land’ Put Transylvania in the Black?” October 31, 2001, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/10/1031_wiredracular2.html, 1 & Jamal and Tanase, “Impacts and Conflicts Surrounding Dracula Park, Romania,” 5. 29 Simeon Alb, email message to author, November 19, 2010 & Jonathan Luxmoore, “Cancellation of Dracula Park Hailed as Victory by Romanian Church,” Ecumenical News International, April 6, 2006. 30 Florescu and McNally, Prince of Many Faces, 176-177. 31 McNally and Florescu, In Search of Dracula, 108. 32 Constantin Rezachevici, “The Tomb of Vlad łepeş: the Most Probable Hypothesis,” Journal of Dracula Studies, 4 (2002), 3. 33 McNally and Florescu, In Search of Dracula, 113. 34 Malcolm Browne, “Dracula’s Bones Mislaid in Rumania,” New York Times, July 27, 2974, 31. 35 Personal research trip to Snagov Monastery, July 2011. 36 Baddeley and Woods, Vlad the Impaler, 305. 128 37 Florescu and McNally, Prince of Many Faces, 173-174 & Elizabeth Miller, Reflections on Dracula: Ten Essays (White Rock: Transylvania Press, 1997), 5; & Duncan Light, “The Status of Vlad łepeş in Communist Romania, a Reassessment,” Journal of Dracula Studies 9 (2007), 2. 38 Light, “Status of Vlad łepeş,” 5 & Duncan Light, “When Was Dracula Translated into Romanian?” Journal of Dracula Studies 11 (2009), 4 & Michael Vorsino “The Dragon, the Raven, and the Ring’ Journal of Dracula Studies 5 (2003), 1. 39 Light, “Status of Vlad łepeş,” 8. 40 Baddeley and Woods, Vlad the Impaler, 17. 41 Baddeley and Woods, Vlad the Impaler, 288. 42 John Darnton, “Count Dracula as Early Rumanian Freedom Fighter,” New York Times, December 16, 1979, 66. 43 Baddeley and Woods, Vlad the Impaler, 220 & Travers, “Vlad the Unique Selling Point,” 1. 44 Goldschlager, “There Was a Count Dracula and He Was Not a Good Old Boy,” 9. 45 Personal research trip throughout Romania, July 2011. 46 Baddeley and Woods, Vlad the Impaler, 28. 47 Samira Beavis, “Dracula Land Plans Kept in Dark,” April 4, 2001, http://abcnews.go.com/International/story?id=81304&page=1, 1 & Baddeley and Woods, Vlad the Impaler, 23. 48 Baddeley and Woods, Vlad the Impaler, 166. 49 Wright, “A House Tour of Dracula’s Castle,” 1. 50 Wright, “A House Tour of Dracula’s Castle,” 1. 51 Light, “When Was Dracula Translated into Romanian?” 8. 52 Baddeley and Woods, Vlad the Impaler, Image 1. 129