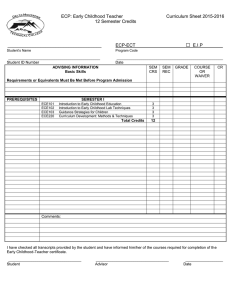

Preparing Early Childhhood Teachers

advertisement