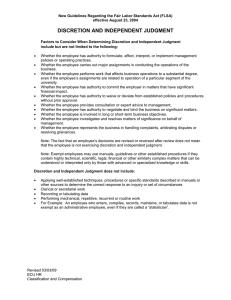

The Model of Rules - University of Maryland Institute for Advanced

advertisement