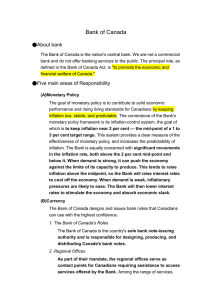

Monetary Policy Report, December 2015

advertisement