Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 February

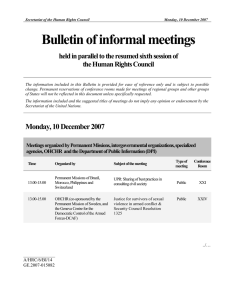

advertisement