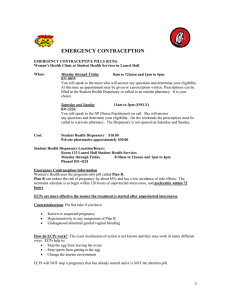

Emergency Contraceptive Pills

advertisement

Emergency Contraceptive Pills: An Important Option for Young Adults 6/13/12 9:33 AM Emergency Contraceptive Pills: An Important Option for Young Adults July 1998 Young women under the age of 24 are more likely than older women to have an unplanned pregnancy, even where contraceptives are readily available. Several factors account for this. Sex among young adults may be unplanned and sporadic.1 Youth, both married and unmarried, are commonly ineffective users of contraceptives as they begin to establish their sexual and birth control practices.2 Often they are poorly informed about sexuality and reproductive health. They may believe myths, for example, that a woman cannot get pregnant the first time she has sex. Emergency Contraceptive Pills (ECPs)—a contraceptive which can be used up to 72 hours after unprotected sex—are an important option for young adults. Because ECPs prevent unintended pregnancy, they also help avert abortion and maternal morbidity and mortality. ECPs may also help sexually active young people realize that they need to begin using regular contraception.3 It is important that young men and women know about ECPs, so that if they have unprotected sex and find themselves facing the possibility of an unplanned pregnancy and its health and social consequences, they know that they can still act to prevent this occurrence. What are Emergency Contraceptive Pills and how do they work? ECPs contain a special regimen of the same hormones as regular oral contraceptives (OCs). They are reserved for an emergency that might produce a pregnancy—a broken condom or slipped diaphragm, non-use of contraception, or rape. A woman using ECPs takes two doses, twelve hours apart, of particular formulations of regular OCs, normally containing estrogen and a progestin.4 An alternate regimen of progestin-only pills—as effective as combined OCs but with a lower incidence of side effects—is also available in some countries. With either regimen, the first dose is taken as soon after unprotected sex as possible, but no later than 72 hours afterwards. ECPs reduce the risk of pregnancy by about 75%. This rate is calculated using the following estimation: if 100 women have a single act of unprotected intercourse in the second or third week of their menstrual cycle, only two would become pregnant if they used ECPs as compared to the eight expected to become pregnant without use of the contraceptive.5 Informational materials, such as Pathfinder International’s training curriculum, provide detailed information on the formulation, dosages, and clinical management of emergency contraceptive pills.6 Some women experience nausea and vomiting for a day or so when using ECPs. Other possible side effects include spotting, temporary breast tenderness, headaches, dizziness and fatigue. http://www.pathfind.org/pf/pubs/focus/IN%20FOCUS/emcon%20final.html Page 1 of 5 Emergency Contraceptive Pills: An Important Option for Young Adults 6/13/12 9:33 AM Depending on when in her cycle a woman uses them, ECPs may work in several ways. Studies show that if a woman has not ovulated, ECPs can stop or delay ovulation. Delaying ovulation may be the main or only mechanism of action. Although there is little evidence, researchers hypothesize that ECPs may also work in other ways.7 If a woman has ovulated, ECPs may prevent fertilization; hinder the transport of a fertilized egg down the fallopian tube, causing it to reach the uterus at the wrong time; or prevent implantation in the uterus.8 More research is needed to determine if any of these mechanisms actually contribute to the effectiveness of ECPs. ECPs cannot cause abortion. The medical community and regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration define pregnancy as beginning after the implantation of a fertilized egg.9 ECPs cannot affect an implanted embryo. If used during an early pregnancy, the best evidence suggests that there will be no harmful effects to the woman or fetus.10 What are the advantages of ECPs for youth? ECPs form an important safety net by providing a backup method in cases of unprotected sex.11 For young people who are not prepared for a sexual experience or had involuntary sex, ECPs offer a second chance at contraception. ECPs provide youth who have not previously sought services with an introduction to reproductive health care.12 Family planning programs can provide ECPs and counseling for sexually active young people either in advance of need, to be kept on hand in case of an emergency, or for use within 72 hours of unprotected sex. Advance distribution with adequate counseling and follow-up is most important for youth using barrier methods, which fail more often than hormonal contraceptives do. Some young adult reproductive health experts advocate the provision of a package of ECPs with condoms, and vice versa.13 ECPs aid sexually active young people as they move to sustained contraceptive use.14 ECPs should be viewed as a bridge to regular contraception, because regular contraceptives have higher efficacy rates. For example, the unintended pregnancy rate for condoms, as commonly used, is about 14% of women in the first year of use.15 What are the drawbacks of ECPs? Like all hormonal contraceptives, ECPs do not protect against STDs, including HIV. Because many young women do not act until they have missed a menstrual period, they may miss the opportunity to use ECPs to prevent pregnancy.16 Because ECPs are only effective for 72 hours after unprotected sex, it should be made clear to youth that contraception is needed for further acts of intercourse. ECPs do not provide protection for the rest of a woman’s monthly cycle. What have been the experiences of programs offering ECPs for youth? The use of ECPs is limited in many countries, even though the effectiveness of the pills in an emergency has been known to the medical community for three decades.17 Despite the limitations, more and more women have been hearing about ECPs and asking their providers for them. In most countries, women can obtain ECPs only through service providers, although in some countries contraceptive pill packages are available over the counter or through community outreach workers. Some European countries—the United Kingdom, for example—have contraceptive pills packaged specifically for emergency use.18 http://www.pathfind.org/pf/pubs/focus/IN%20FOCUS/emcon%20final.html Page 2 of 5 Emergency Contraceptive Pills: An Important Option for Young Adults 6/13/12 9:33 AM Women use ECPs widely in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, where they form part of an integrated reproductive health service and are covered in the national health insurance systems.19 The experience of the Netherlands demonstrates the acceptability of ECPs among youth: in 1991, 70% of Dutch women receiving ECPs from general practitioners were less than 25 years old, and 34% were younger than 20.20 Cost data from the United Kingdom indicate that providing ECPs and counseling ranges between $19 and $74, depending on the provider.21 In developing countries, the understanding now is that the public sector purchase price will be about 25 cents to governmental agencies, NGOs and social marketing organizations.22 What are the barriers to the use of ECPs by young adults? Despite the importance and efficacy of ECPs, youth in need of emergency contraception face frustrating barriers. Many young people are not aware of the existence of ECPs as a means to prevent unintended pregnancy. Health service providers are also often poorly informed about emergency contraception and although there is no evidence to support the concern that ECPs encourage promiscuity, providers frequently give this as a reason for not providing ECPs to youth. Most providers in a Vietnamese study overestimated the incidence and severity of side effects and cited incorrect contraindications. Some providers stated that they did not promote ECPs because of the lack of publicized research findings, and the majority believed that distribution should be strictly controlled.23 Confusion between ECPs and abortion still exists, and this confusion can block efforts to prevent unintended pregnancy, as has been demonstrated in Malaysia.24 While there are some advocates for the provision of ECPs along with condoms, one study of university health centers in the United States shows that some providers are concerned about this approach. These providers believe that telling students to use condoms to prevent pregnancy and STDs—and then also offering ECPs because of the risk of condom breakage—sends a mixed message about the effectiveness of condoms.25 Are there ECP programs underway in developing countries? Despite such barriers, family planning programs are working globally to make ECPs known and available. For example, the International Planned Parenthood Federation affiliate in Colombia, PROFAMILIA, holds daily educational activities for youth, their parents and teachers. Educators include information on ECPs in their sessions on reproductive health. Young people want to know what ECPs contain; how they work; if they cause abortion; and about their safety, legality and side effects. PROFAMILIA staff instruct youth to use ECPs only for emergencies and encourage them to share information about ECPs with their peers.26 However, most of the programs making ECPs available to youth in developing countries remain in the pilot phase. They have not yet yielded experiential information or data. Despite this, examples of these newer programs are still useful. The Fertility Research Unit at the College of Medicine in Ibadan, Nigeria, has embarked on a three-year pilot project in six reproductive health and family planning centers. The Youth Clinic of the Association for Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH) is one of these sites. Grace Delano of ARFH calls ECPs "lifesaving,"27 in support of the project’s aim to increase access to ECPs, especially among youth aged 15-24.28 Even young men visit ARFH clinics wanting ECPs for their partners. ARFH counselors take http://www.pathfind.org/pf/pubs/focus/IN%20FOCUS/emcon%20final.html Page 3 of 5 Emergency Contraceptive Pills: An Important Option for Young Adults 6/13/12 9:33 AM this opportunity to tell youth not to rely on this emergency method, i.e., that to avoid anxiety about a possible unplanned pregnancy, sexually active young people should adopt a regular contraceptive method. The Kenya Medical Women’s Association and the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH) have put together a short story, "What adolescents need to know about emergency contraception." The story opens with a young woman worried about pregnancy after having unplanned sex for the first time. Fortunately, the girl’s mother discovers what has happened and gives her daughter the facts about ovulation and fertilization. At her mother’s insistence, the girl visits a doctor to get ECPs and avoids a possible pregnancy, and then vows not to have sex until marriage. The story ends by encouraging youth to spread the news about emergency contraception to their friends who have had unprotected sex.29 The Mexico City-based Medical Center at the National University of Mexico has a pilot project with the Population Council offering students ECP counseling and medical services.30 In addition, the Mexican Family Planning Foundation (MEXFAM) and the Mexican Institute for Family and Population Research (IMIFAP) have put together educational materials in Spanish for youth on ECPs and made them available via print and the Internet.31 What is the take-home message? ECPs are an important emergency contraceptive option for sexually active young people. Because of barriers surrounding the issue of youth sexuality and the confusion between ECPs and abortion, ECPs are underutilized. When ECPs are made available and accessible to youth, they are well accepted. They help reduce the incidence of unplanned pregnancies and abortions, especially with proper counseling. They can also help youth realize the significance of contraception and lead them to use a more reliable method on an ongoing basis. REFERENCES 1 Family Health International. Spring 1997. "Contraceptive Methods for Young Adults: Emergency Contraception." Network 17 (3): 16-17. 2 Glasier A. et al. June 1996. "Case Studies in Emergency Contraception from Six Countries." International Family Planning Perspectives 22 (2): 57-61. 3 Ibid. 4 USAID Fact Sheet on Emergency Contraception. October 1997. (Unpublished document provided by J. Spieler, Chief, Research Division, Office of Population, United States Agency for International Development.) 5 Ibid. 6 Farrell B., C. Solter, and D. Huber. 1997. Module 5: Emergency Contraceptive Pills, Comprehensive Reproductive Health and Family Planning Training Curriculum. Watertown, MA: Pathfinder International. (To request this document, contact Ms. Carol Wall at 617-924-7200, fax - 617-924-3833, or email <cwall%6381752@mcimail.com>.) 7 USAID Fact Sheet on Emergency Contraception, op. cit. 8 American Medical Association. October 2, 1996. Birth Control Enters the 21st Century with More Alternatives. In Science News Update [Online, cited September 10, 1997]. Available online: <http://www.ama-assn.org/sci-pubs/scinews/1996/ snr1002.htm >. 9 USAID Fact Sheet on Emergency Contraception, op. cit. 10 Technical Guidance/Competence Working Group. September 1997. In Recommendations for Updating Selected Practices in Contraceptive Use, edited by Monica Gaines: Vol. 2, 134. 11 Glasier et al., op. cit. 12 Farrell et al., op. cit. 13 Robinson E.T., M. Metcalf-Whittaker, R. Rivera. June 1996. "Introducing Emergency Contraceptive Services: Communications Strategies and the Role of Women's Health Advocates." International Family Planning Perspectives 22 (2): 71-75. 14 Glasier et al., op. cit. 15 Huber D. 1998. Personal communication, May. 16 Stewart L. 1998. Personal communication, January. http://www.pathfind.org/pf/pubs/focus/IN%20FOCUS/emcon%20final.html Page 4 of 5 Emergency Contraceptive Pills: An Important Option for Young Adults 6/13/12 9:33 AM 17 USAID Fact Sheet on Emergency Contraception, op. Cit. 18 Consortium for Emergency Contraception. Questions and Answers for Decision Makers, [Online, cited August 5, 1997] Available online: <http://www.path.org/ecconsor/qna.html>. 19 Glasier, A. et al. March/April 1996. "Emergency Contraception in the UK and the Netherlands." Family Planning Perspectives 28 (2): 49-51. 20 Glasier et al., "Case Studies in Emergency Contraception," op. cit. 21 Ibid. 22 Huber, D. 1998. Personal communication, May. 23 Nguyen T.N.N., et al. June 1997. "Knowledge and Attitudes About Emergency Contraception Among Health Workers in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam." International Family Planning Perspectives 23(2): 68-72. 24 Glasier et al., "Case Studies in Emergency Contraception," op. cit. 25 Harper C., and C. Ellertson. July/August 1995. "Knowledge and Perceptions of Emergency Contraceptive Pills Among a College-Age Population: A Qualitative Approach." Family Planning Perspectives 27 (4): 149-154. 26 Vargas C. 1997. Personal communication, August. 27 Delano, G. 1997. Personal communication, September. 28 Association for Reproductive and Family Health. March 1997. Emergency Contraceptive Pills: Proceedings of Two-day Orientation Seminar. Ibadan, Nigeria. 29 Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH) for The Kenya Medical Women’s Association. 1996. What Adolescents Need to Know about Emergency Contraception. Nairobi, Kenya 30 Solórzano Harris, E.M. 1998. Personal communication, February. 31 Pick, S. 1998. Personal communication, April. u The In Focus series summarizes for professionals working in developing countries some of the program experience and limited research available on young adult reproductive health concerns. This issue was prepared by Ann Klofkorn and was reviewed by the FOCUS Editorial Board, some outside experts and the staff of the FOCUS program. The In Focus publication series is available on the FOCUS web site: http://www.pathfind.org/focus.htm http://www.pathfind.org/pf/pubs/focus/IN%20FOCUS/emcon%20final.html Page 5 of 5