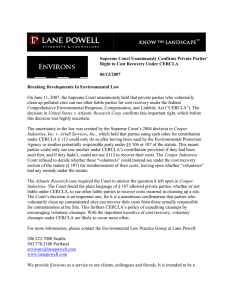

duty of care for the bona fide prospective purchaser exemption from

advertisement