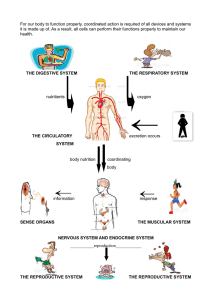

“Workplace Hazards to Reproduction and Development,” Technical

advertisement