Differences exist in the eating habits of university men and women at

advertisement

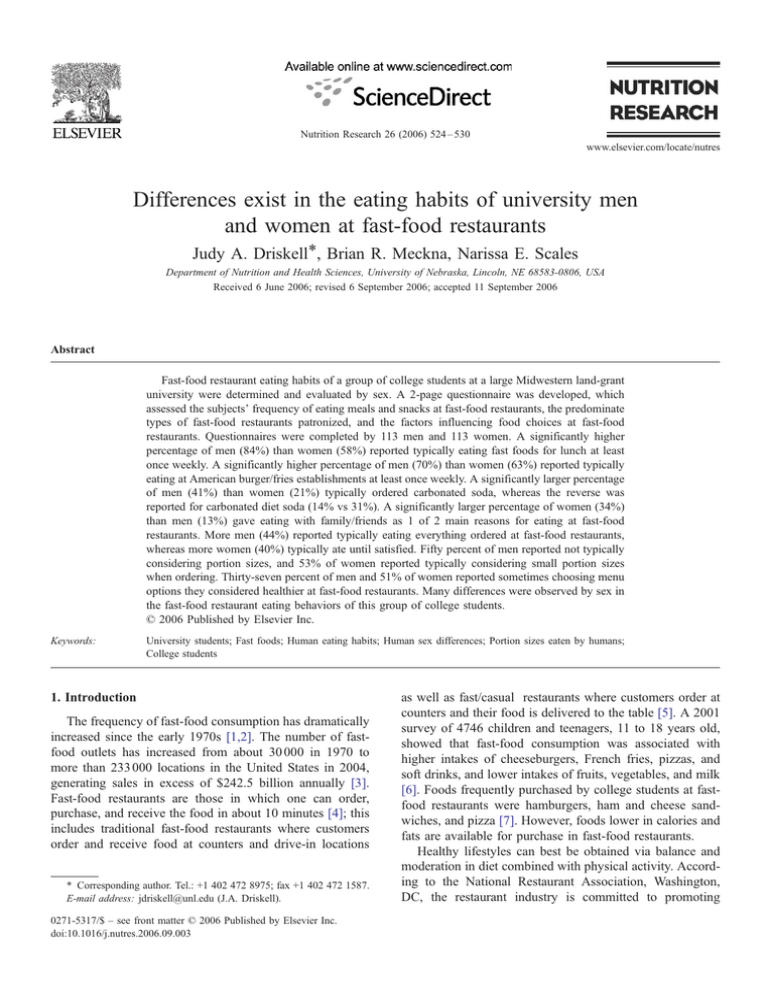

Nutrition Research 26 (2006) 524 – 530 www.elsevier.com/locate/nutres Differences exist in the eating habits of university men and women at fast-food restaurants Judy A. Driskell4, Brian R. Meckna, Narissa E. Scales Department of Nutrition and Health Sciences, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68583-0806, USA Received 6 June 2006; revised 6 September 2006; accepted 11 September 2006 Abstract Fast-food restaurant eating habits of a group of college students at a large Midwestern land-grant university were determined and evaluated by sex. A 2-page questionnaire was developed, which assessed the subjects’ frequency of eating meals and snacks at fast-food restaurants, the predominate types of fast-food restaurants patronized, and the factors influencing food choices at fast-food restaurants. Questionnaires were completed by 113 men and 113 women. A significantly higher percentage of men (84%) than women (58%) reported typically eating fast foods for lunch at least once weekly. A significantly higher percentage of men (70%) than women (63%) reported typically eating at American burger/fries establishments at least once weekly. A significantly larger percentage of men (41%) than women (21%) typically ordered carbonated soda, whereas the reverse was reported for carbonated diet soda (14% vs 31%). A significantly larger percentage of women (34%) than men (13%) gave eating with family/friends as 1 of 2 main reasons for eating at fast-food restaurants. More men (44%) reported typically eating everything ordered at fast-food restaurants, whereas more women (40%) typically ate until satisfied. Fifty percent of men reported not typically considering portion sizes, and 53% of women reported typically considering small portion sizes when ordering. Thirty-seven percent of men and 51% of women reported sometimes choosing menu options they considered healthier at fast-food restaurants. Many differences were observed by sex in the fast-food restaurant eating behaviors of this group of college students. D 2006 Published by Elsevier Inc. Keywords: University students; Fast foods; Human eating habits; Human sex differences; Portion sizes eaten by humans; College students 1. Introduction The frequency of fast-food consumption has dramatically increased since the early 1970s [1,2]. The number of fastfood outlets has increased from about 30 000 in 1970 to more than 233 000 locations in the United States in 2004, generating sales in excess of $242.5 billion annually [3]. Fast-food restaurants are those in which one can order, purchase, and receive the food in about 10 minutes [4]; this includes traditional fast-food restaurants where customers order and receive food at counters and drive-in locations 4 Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 402 472 8975; fax +1 402 472 1587. E-mail address: jdriskell@unl.edu (J.A. Driskell). 0271-5317/$ – see front matter D 2006 Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2006.09.003 as well as fast/casual restaurants where customers order at counters and their food is delivered to the table [5]. A 2001 survey of 4746 children and teenagers, 11 to 18 years old, showed that fast-food consumption was associated with higher intakes of cheeseburgers, French fries, pizzas, and soft drinks, and lower intakes of fruits, vegetables, and milk [6]. Foods frequently purchased by college students at fastfood restaurants were hamburgers, ham and cheese sandwiches, and pizza [7]. However, foods lower in calories and fats are available for purchase in fast-food restaurants. Healthy lifestyles can best be obtained via balance and moderation in diet combined with physical activity. According to the National Restaurant Association, Washington, DC, the restaurant industry is committed to promoting J.A. Driskell et al. / Nutrition Research 26 (2006) 524–530 healthy lifestyles [8]. The average American eats out about 4 times weekly [9], frequently at fast-food restaurants. College students have been reported to eat meals at fastfood restaurants 6 to 8 times weekly [10]. Hence, foods eaten at fast-food restaurants do substantially contribute to the nutrient intakes of individuals in the United States, especially college students. Most college students’ dietary intakes do not meet daily recommendations for most of the food groups [11]. The 1995 National College Health Risk Behavior Survey found that 74% of college students did not eat the recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables per day and 22% had eaten 3 or more high-fat foods daily [12]. These behaviors are of particular concern to nutrition professionals because dietary knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors that are developed and exhibited during college may carryover to adulthood and strongly influence future health status [11]. One of the Healthy People 2010 objectives is to increase the proportion of college and university students who receive information on dietary practices that cause disease [13]. A few studies have been done in the last couple of decades on reasons why college students eat at fast-food restaurants, though the reasons given may be different today than 10 to 15 years ago. These reasons include menu choices, cost, convenience [10,14], taste, cost [10], socializing with friends, and a chance to get out [15]. Information is not available as to whether the reasons that men eat at fast-food restaurants are different from those of women. College men have been reported to consume more highenergy and high-fat foods than women [7]. The recommendations for food energy and for many of the essential nutrients are different for men and women [16-21]. A better understanding of the influence of sex on the eating habits of college students is needed, and likely, differences do exist. College students often frequent fast-food restaurants. The purpose of this study was to determine the fast-food restaurant eating habits of a group of college students at a large Midwestern land-grant university and determine if differences exist by sex. The frequency of eating meals and snacks at fast-food restaurants, the predominate types of fast-food restaurants patronized, and the factors influencing food choices at fast-food restaurants were determined. 2. Methods and materials 2.1. Subjects The institutional review board of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Neb, approved the project. Participants, 19 years and older, were recruited from an introductory nutrition course at a large Midwestern landgrant university during the fifth week of the fall semester, 2004. Introductory nutrition is one of the choices of courses that students can select to meet or partially meet the science requirement in all colleges of this university except one. This course has no prerequisites; 95% of enrolled students 525 took the course to meet or partially meet their science requirement. Subjects were generally representative of undergraduate students at our university. Ninety-nine percent of eligible students participated; all signed informed consent forms. More women than men completed the questionnaire; hence, questionnaires from the women were randomly selected (random numbers) for inclusion in the study so that an equal number of men and women served as subjects. Nine of the subjects completed the questionnaire a second time after 4 weeks; their response reliability was 77.2%. 2.2. Questionnaire development A 2-page written questionnaire was developed using previously published findings [7,14,15,22-24] as well as questions about the influence of nutritional information on food choices, portion sizes, and food choices students considered as being healthier. A Likert-type scale with 2(yes, no), 3-, 4-, or 5-point responses [25] was used in constructing responses for each question included in the questionnaire. So that participants were aware of what was meant by fast-food restaurant, the definition was placed on the top of the questionnaire. The 10-item questionnaire consisted of the following questions: age of 19 years or older; sex; number of times a week (0, 1-2, 3-4, 5+) a subject typically eat at fast-food restaurants (breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snack); how many times (0, 1-2, 3-4, 5+) a subject typically patronized each of several types of fast-food restaurants (American burger/fries, Asian, deli sandwich, Italian, Mexican, ice cream, other); type of beverage (no drink, water, carbonated soda, carbonated diet soda, fruit juice, milk and shakes, lemonade, tea, other) typically ordered; 2 primary reasons for choosing to eat fast food (selection of 2 from the following: advertisements, enjoy the taste, lack of cooking skills, limited time, location, cost, to eat with friends/family, variety of menu, other); eating until satisfied, eating everything ordered, or both; portion sizes typically ordered (small, large, or do not consider portion sizes) and why (health/weight issues, hunger, value for money, other); influence of nutritional information on the choices made regarding fast food (not at all, rarely, sometimes, most of the time, or always); and how often options students considered healthier were chosen at fast-food restaurants (not at all, rarely, sometimes, most of time, or always). Local examples of each of the types of fast-food restaurants were also listed on the questionnaire. The questionnaire was validated before the start of the study by 10 faculty members in nutrition and health sciences, some of whom had expertise in food service. Ten students pilot tested the survey to clarify language and response options. 2.3. Statistical analyses The data were analyzed by sex using the v 2 test for association in contingency tables [26] implemented in SAS PROC FREQ [27] software (SAS Institute, version 8, 1999, 526 J.A. Driskell et al. / Nutrition Research 26 (2006) 524–530 3.2. Times/week eating at various types of fast-food restaurants The types of fast-food restaurants that the subjects typically patronized most prevalently, that is, at least once weekly, were deli sandwich, 73%; American burger/fries, 62%; and Mexican, 53% (Table 1). A significant difference ( P b .05) by sex was observed in the frequency of weekly visits to American burger/fries establishments, with 30% of men and 47% of women reporting not typically eating at American burger/fries establishments. No sex differences were observed with regard to the other types of fast-food restaurants. Fig. 1. Percentages of male (M) and female (F) university students that reported typically eating breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snack 0, 1 to 2, 3 to 4, and 5+ times weekly at fast-food restaurants. v 2 analyses indicated that significant differences ( P b .05) by sex were observed for breakfast and lunch. 3.3. Beverage typically ordered with fast-food meal or snack The subjects included 113 men and 113 women, 19 years and older. Thirteen percent of the subjects were freshmen; 24%, sophomores; 44%, juniors; and 19%, seniors. A significant difference ( P b .05) was observed in the type of beverage that men and women typically ordered with a fast-food meal or snack. The most frequently ordered beverages were carbonated soda, carbonated diet soda, and water. Forty-one percent of men ordered carbonated soda compared with 21% of women; 31% of women ordered carbonated diet soda compared with 14% of men. Water was typically ordered by 32% of women and 23% of men. Lemonade and tea were ordered 4% to 9% of the time; no beverage, 4% of the time; fruit juice, 1% to 3% of the time; and milk or shake as well as other beverage, less than 1% of the time. 3.1. Frequency of eating at fast-food restaurants 3.4. Primary reasons for choosing to eat fast food The frequencies at which the male and female subjects reported typically consuming breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snack at fast-food restaurants are given in Fig. 1. Significant differences ( P b .05) were observed between the responses of men and women with regard to typically eating breakfast and lunch, but not dinner or snack, at fast-food restaurants. Most of the subjects (89%) reported not typically eating breakfast at fast-food restaurants, with 83% of men and 95% of women reporting not typically eating breakfast at fastfood restaurants. Eighty-four percent of men and 58% of women reported typically eating fast foods for lunch at least once weekly. Eighty-two percent of subjects typically ate dinner at fast-food restaurants at least once weekly. Twentynine percent of subjects typically ate a snack at fast-food restaurants weekly. The 2 primary reasons the subjects gave for choosing to eat fast food (Fig. 2) were limited time (71% of subjects) and enjoy the taste (41%). Other less frequently selected reasons were to eat with friends or family, location, cost, lack of cooking skills, variety of menu, advertisements, and other reasons. Responses of the subjects by sex were similar with the exception that a significantly larger ( P b .0005) percentage of women (34%) than men (13%) indicated that 1 of the 2 primary reasons for choosing to eat at fast-food restaurants was to eat with friends and family. Cary, NC). The findings are presented as percentages of subjects. Differences were considered significant at P b .05. 3. Results 3.5. Eating until satisfied, everything ordered, or both A significant difference ( P b .01) was observed between men and women as to whether they typically ate at a fastfood restaurant until they were satisfied, ate everything Table 1 Percentages of university male and female students that reported typically eating at various types of fast-food restaurants 0, 1 to 2, 3 to 4, and 5+ times weekly Type of fast-food restaurant American burger/friesa Asian Deli sandwich Italian Mexican Ice cream Other a Male 0 30.1 69.0 24.8 59.3 44.3 77.9 96.4 1-2 58.4 30.1 65.5 38.1 54.9 21.2 3.6 Female 3-4 8.9 0.9 8.0 1.8 0.9 0.9 0.0 5+ 2.7 0.0 1.8 0.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 0 46.9 81.4 29.2 64.0 49.6 69.0 98.2 v 2 analyses indicated that the responses of males were significantly different ( P b .05) than those of females. 1-2 48.7 18.6 66.4 35.1 47.8 29.2 0.9 3-4 1.8 0.0 3.5 0.9 2.7 1.8 0.9 5+ 2.7 0.0 0.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 J.A. Driskell et al. / Nutrition Research 26 (2006) 524–530 527 of the subjects, with an equal percentage of the sex groups (40%), was that they sometimes made choices regarding fast-food choices based on nutrition information. 3.8. Selection of healthier options A significant difference ( P b .01) was observed by sex as to how often subjects reported choosing options they considered healthier at fast-food restaurants. The responses by sex were (male vs female) not at all, 14% vs 2%; rarely, 23% vs 18%; sometimes, 37% vs 51%; most of the time, 21% vs 24%; and always, 5% vs 5%. 4. Discussion Fig. 2. Responses given by male and female university students as 1 of their 2 primary reasons for choosing to eat fast food. Subjects selected 2 reasons (advertisement, enjoy the taste, lack of cooking skills, limited time, location, cost, eat with friends/family, variety of menu, and other). v 2 analysis indicated that a significantly larger ( P b .05) percentage of females gave to eat with friends/family than males as 1 of their 2 reasons. ordered, or both. Twenty-one percent of men indicated that they typically ate until they were satisfied, 44% ate everything ordered, and 35% selected both; 40% of women indicated that they typically ate until they were satisfied, 39% ate everything ordered, and 21% selected both. 3.6. Portion sizes considered and reasons given A significant difference ( P b .0001) was observed between men and women as to whether they typically considered smaller portion sizes, larger portion sizes, or did not consider portion sizes when ordering a meal at fast-food restaurants. Fifty percent of the men reported not typically considering portion sizes, whereas 53% of the women reported considering smaller portion sizes. There were no differences by sex as to the reasons (health/weight issues, hunger, value for money, and other) selected by subjects for considering portion sizes (Fig. 3); students could select only one of the listed reasons. Of the 78 subjects that indicated considering smaller portion sizes, more than half gave health/weight issues as the reason for considering smaller portion sizes. More than half of the 50 subjects that indicated considering larger portion sizes gave hunger as the reason for considering larger portion sizes. The predominant responses that the 98 subjects selected for not considering portion sizes were hunger and value for money, both of which received more than one third of responses. College students reportedly skip meals, especially breakfast [10,22]. Few students in the current study (11%) reported typically eating breakfast at a fast-food restaurant, though they may have eaten breakfast elsewhere. According to a 2003 survey of a group of undergraduate students at our university, 57% reported typically eating breakfast, and more than 90% reported typically eating meals at fast-food restaurants 6 to 8 times weekly [10]. The meals of choice of the subjects in the current study eaten at fast-food restaurants were lunch and dinner, mostly 1 to 2 times weekly. More than 29% of these subjects reported eating snacks at fast-food restaurants. Significantly larger percentages of women than men reported not eating breakfast and lunch at fast-food restaurants in the current study. College men have been reported to eat more fast foods than women [7]. College men have been reported as being more likely than college women to eat breakfast and less likely to skip meals as a means of weight control [23]. 3.7. Influence of nutrition information on choices made regarding fast-food choices A significant difference ( P b .01) was observed between men and women as to how much (not at all, rarely, sometimes, most of the time, and always) nutrition information influenced the choices they made regarding fast food. Females more often selected most of the time (35%) than males (23%), and males more often selected not at all (16%) than females (3%). The predominant response Fig. 3. Percentages of male (M) and female (F) university students giving health/weight issues, hunger, value for money, and other as reasons for typically considering ordering smaller portion sizes, larger portion sizes, or not considering portion sizes when ordering a meal at fast-food restaurants. Students could select only one of the above reasons. v 2 analysis indicated that a significant difference ( P b .01) was observed by sex as to whether students typically considered ordering smaller portion sizes, larger portion sizes, or not considering portion sizes when ordering a meal at fast-food restaurants. 528 J.A. Driskell et al. / Nutrition Research 26 (2006) 524–530 College students in the present study patronized a variety of types of fast-food restaurants at least 1 to 2 times weekly. The most popular choices were the fast-food restaurants classified as deli sandwich, American burger/fries, and Mexican. Huang et al [7] reported that hamburgers, ham and cheese sandwiches, and pizzas were popular selections of college students. The 2 beverages most typically ordered by subjects in the current study were carbonated soda and carbonated diet soda. As expected, a larger percentage of women consumed carbonated diet soda than men, whereas the reverse was true for carbonated soda. Fast food, pizza, and other types of restaurants provided 25% of the soda consumed by teenaged girls, 12 to 19 years old [24]. Menu choices, cost, and convenience have been reported as being related to the number of meals college students ate in fast-food restaurants [10,14]. College students included in a 2003 survey at our university indicated that their food choices, not just at fast-food restaurants, were most influenced by convenience, taste, and cost [10]. One third of the women in the current study indicated that 1 of the 2 primary reasons for choosing to eat fast foods was to eat with friends and family. Hertzler and Frary [15] reported that socializing with friends and a chance to get out were the top 2 choices of college students for eating fast foods. The predominate 2 reasons given by subjects in the current study for eating at fast-food restaurants were limited time and taste. Seemingly, college students today want to spend little time eating at least some meals, and they tend to like the taste of fast foods, perhaps because they have become accustomed to eating fast foods. More than half of American adults polled in 2006 indicated that they decided how much food to eat at a single sitting based on the amount they were served [28]. In a subsequent survey, 70% of American adults polled indicated that when dining out, they finished their entrées all or most of the time [29]. The amount of food that is presented during a single meal directly influences energy intake [30]. Half of the men included in the current study reported not typically considering portion sizes when ordering at fast-food restaurants, whereas more than half of the women reported considering smaller portion sizes. Sex-specific brain responses to a meal indicate possible differences by sex in the cognitive and emotional processes of hunger and satiety [31]. Such brain responses may relate to differences by sex relating to the selection of portion sizes and eating until satisfied or eating everything ordered. Women have been reported as more likely to be trying to lose weight than men [32]; this may help explain this disparity between men and women. A study involving 131 female college students indicated that more than 54% were not satisfied with their body weight; both women and men used less consumption of high fat foods as a way to lose weight [33]. Female college students have been reported to be less accurate in their perceptions of their body weights than males [34]. This may explain why a larger percentage of the college women than men in the current study considered ordering smaller portion sizes when eating at fast-food restaurants. Most men and women included in the current study gave health/weight issues as the reason for considering ordering smaller portion sizes. Hunger and value for money were reasons given by those subjects for not considering portion sizes when ordering at fast-food restaurants. Female college students in the current study more often indicated that nutritional information influenced their food choices at fast-food restaurants than men. Food labeling has been reported to influence the food choices made by college students [35]. The types of nutrition information a group of college students indicated that they wanted on the internet were body image and weight concerns, student personalization features, healthy eating on a budget, healthy meal planning, basic nutrition facts, and expert nutrition information [36]. Hence, perhaps the easy availability of reputable nutritional information may influence the food choices made by college students. Most of the college students in the present study indicated at least sometimes choosing options they considered healthier at fast-food restaurants, with a larger percentage of women than men selecting sometimes or most of the time. Today, most, if not all, fast-food restaurants have responded to consumer concerns and offer some healthier food choices. Significant differences were observed by sex with regard to many of the fast-food eating behaviors of college students included in the present study. Most of the college students in the current study typically ate lunch and dinner at fast-food restaurants at least once weekly, with a larger percentage of men than women typically eating lunch at fast-food restaurants. More than half of the students reported typically eating at deli sandwich, American burger/fries, and Mexican fast-food restaurants at least once weekly, with a larger percentage of men than women eating more frequently at the American burger/fries restaurants. A larger percentage of men ordered carbonated soda, and women, diet carbonated soda. Limited time and enjoy the taste were the 2 main reasons subjects gave for choosing to eat fast food. Women more often than men gave the reason of eating with friends/family. A larger percentage of men than women indicated that they typically ate everything ordered, whereas a larger percentage of women than men reported typically eating until they were satisfied. A larger percentage of men reported not considering portion sizes when ordering at fast-food restaurants, whereas a larger percentage of women reported considering ordering smaller portion sizes. The reason most subjects gave for considering ordering various portion sizes were, for smaller portion sizes, health/weight issues; for larger portion sizes, hunger; and for not considering portion sizes, hunger and value for money. Thirty-five percent of women and 23% of men indicated that nutrition information influenced the choices they made J.A. Driskell et al. / Nutrition Research 26 (2006) 524–530 regarding fast food most of the time. A larger percentage of women than men reported sometimes choosing options they considered healthier at fast-food restaurants. The findings of the current study cannot be generalized for all college students’ fast-food eating behaviors throughout the United States; however, these findings are in agreement with the limited number of studies published on the topic, though most of these were published over a decade ago and food habits often change over time. The consumption of foods at fast-food restaurants appears to be common among college students, and most likely, is part of their lifestyle. Individuals can consume food items that are lower in calories and fats when dining at fast-food restaurants because these types of items are available. The findings of the present study indicate that nutritional consultation and educational materials designed to help college students make good food choices when dining at fast-food restaurants need to be somewhat different for college men than women because several differences in eating habits at fast-food restaurants were observed by sex. Acknowledgment Funding for this research was provided by the Nebraska Agricultural Research Division; this article is their Journal Series 15180. We thank the subjects for their participation in the study. The statistical consultation provided by Erin E. Blankenship, Department of Statistics at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Neb, is appreciated. References [1] Paeratakul S, Ferdinand DP, Champagne CM, Ryan DH, Bray GA. Fast-food consumption among US adults and children: dietary and nutrient intake profile. J Am Diet Assoc 2003;103:1332 - 8. [2] French SA, Harnack L, Jeffery RW. Fast food restaurant use among women in the Pound of Prevention study: dietary, behavioral and demographic correlates. Int J Obes 2000;24:1353 - 9. [3] National Restaurant Association. Quick service restaurant trends. Washington, DC7 National Restaurant Association; 2005. [4] Spears MC. Foodservice organizations: a managerial and systems approach. Upper Saddle River (NJ)7 Prentice Hall; 2003. [5] National Restaurant Association. Quick quality: serving food fast and with finesse (1998). Available from: URL:http://www.restaurant.org/ rusa/mag/Article.cfm?ArticleID = 292 [accessed May 30, 2006]. [6] French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes 2001;25:1823 - 33. [7] Huang Y-L, Song WO, Schemmel RA, Hoerr SM. What do college students eat? Food selection and meal pattern. Nutr Res 1994;24:1143 - 53. [8] National Restaurant Association. Market-driven solutions (2006). Available from: URL:http://www.restaurant.org/pressroom/market_ solutions.cfm [accessed May 30, 2006]. [9] Cohn SR. Diet isn’t the only obesity culprit (2002). Available from: URL:http://www.restaurant.org/pressroom/rapid_response. cfm?ID = 566 [accessed May 30, 2006]. 529 [10] Driskell JA, Kim Y-N, Goebel KJ. Few differences found in the typical eating and physical activity habits of lower-level and upperlevel university students. J Am Diet Assoc 2005;105:798 - 801. [11] Dinger MK, Waigandt A. Dietary intake and physical activity behaviors of male and female college students. Am J Health Promot 1997;11:360 - 2. [12] Centers of disease control, youth risk behavior surveillance: National College Health Risk Behavior Survey—United States. MMWR 1997;46(SS-6):1 - 54. [13] US Department of Health and Human services. Healthy people 2010 (conference edition), US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC; 2000. [14] Sneed J, Holdt CS. Many factors influence college students’ eating patterns. J Am Diet Assoc 1991;91:1380. [15] Hertzler AA, Frary RB. Family factors and fat consumption of college students. J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96:711 - 4. [16] Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Dietary reference intakes for calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, and fluoride. Washington (DC)7 National Academy Press; 1997. [17] Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline. Washington (DC)7 National Academy Press; 1998. [18] Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. Washington (DC)7 National Academy Press; 2000. [19] Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington (DC)7 National Academy Press; 2001. [20] Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington (DC)7 National Academy Press; 2002/2005. [21] Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Washington (DC)7 National Academy Press; 2005. [22] Debate RD, Topping M, Sargent RG. Racial and gender differences in weight status and dietary practices among college students. Adolescence 2001;36:819 - 34. [23] Daniel E. Meal skipping patterns among nutrition students. Available at: URL:http://aahperd.confex.com/aahperd/2005/preliminaryprogram/abstract_6139.htm, [accessed March 15, 2006]. [24] Bowman SA. Beverage choices of young females: changes and impact on nutrient intakes. J Am Diet Assoc 2002;102:1234 - 9. [25] Adams GR, Schvaneveldt JD. Understanding research methods. White Plains (NY)7 Longman; 1985. p. 162 - 4. [26] Steel RGD, Torrie JH, Dickey DA. Principles and procedures of statistics: a biometrical approach. 3rd ed. New York7 The McGrawHill Companies, Inc; 1997. p. 502 - 26. [27] Stokes ME, Davis CS, Kock GG. Categorical data analysis using the SAS system. 2nd ed. Cary (NC)7 SAS Institute; 2000. [28] American Institute for Cancer Research. New survey on portion size: Americans still cleaning plates (2006). Available from: URL:http:// www.aicr.org/site/News2?abbr = pr_&page = NewsArticle&id = 9435 [accessed March 14, 2006]. [29] American Institute for Cancer Research. Resign from the clean plate club (2004). Available from: URL:http://www.aicr.org/site/News2? abbr = pr_&page = NewsArticle&id = 7598 [accessed March 14, 2006]. [30] Rolls BJ, Morris EL, Roe LS. Portion size of food affects energy intake in normal-weight and overweight men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:1207 - 13. [31] Parigi AD, Chen K, Gautier JF, Salbe AD, Pratley RE, Ravussin E, et al. Sex differences in the human brain’s response to hunger and satiation. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;75:1017 - 22. [32] Lowry R, Galuska DA, Fulton JE, Wechsler H, Kann L, Collings JL. Physical activity, food choice, and weight management goals 530 J.A. Driskell et al. / Nutrition Research 26 (2006) 524–530 and practices among US college students. Am J Prev Med 2000;18: 18 - 27. [33] Koszewski WM, Kuo M. Factors that influence the food consumption behavior and nutritional adequacy of college women. J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96:1286 - 8. [34] Beerman KA, Jennings G, Crawford S. The effect of student residence on food choice. J Am Coll Health 1990;38:215 - 20. [35] Marietta AB, Welshimer KJ, Anderson SL. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of college students regarding the 1990 Nutrition Labeling Education Act food labels. J Am Diet Assoc 1999;99: 445 - 9. [36] Cousineau TM, Goldstein M, Franko DL. A collaborative approach to nutrition education for college students. J Am Coll Health 2004;53:79 - 84.