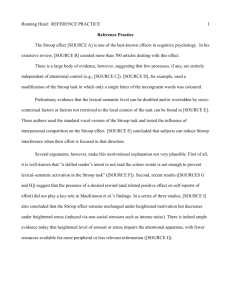

Neg>Pos>Neu

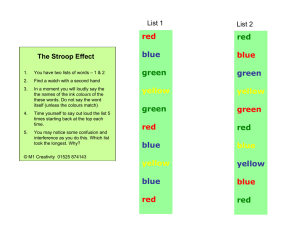

advertisement

Do young and older adults show emotional enhancement effects in memory for incidentally encoded information? Arousal Condition Older High Arousal Low Arousal M age 73.92 72.92 Young M age n 23.25 24 22.42 24 n 25 24 High arousal and low arousal words were selected from the Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW; Bradley & Lang, 1999) and were divided into two sets. Each set contained 72 words (24 positive, 24 negative, and 24 neutral) and was presented in a pseudo-randomized and intermixed order in the main emotional Stroop task (as the incidental encoding task). At encoding, participants completed an emotional Stroop task in which they reported the ink color of each word as quickly and as accurately as possible. After a 2-minute delay, participants completed a surprise free recall task. Encoding (emotional Stroop) Hateful Humble Filler Tasks (2 Minutes) Happy Free Recall 7 Minutes .07 Proportional Recall According to the Socioemotional Selectivity Theory, changing time horizons with aging, such as the perception of reduced time left in their lifespan, leads to motivational shifts. As a result, older adults shift to prioritize social emotional goals (i.e., to enhance well-being) over knowledge-acquisition goals. Driven by this motivational shift, older adults differentially attend to and remember positive information better than negative and neutral information (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005; Charles, Mather, & Carstensen, 2003; Mather & Carstensen, 2005). This positivity effect in old age has been reported with intentional memory paradigms. However, it has been shown that the presence of positivity effects may vary as a function of viewing instructions or the arousal level of testing stimuli (Emery & Hess, 2008; Kensinger, 2008). Furthermore, It is unclear whether age differences in emotional memory would be extended to incidentally encoded task-irrelevant stimuli. To fill the gap, the current study aims to investigate age differences in memory for incidentally encoded words with an emotional Stroop task in which participants name the ink colors of emotional and neutral words. Relatively few studies have conducted emotional Stroop tasks with both young and older adults (Ashley & Swick, 2009; LaMonica et al., 2010; Wurm et al., 2004). To our knowledge, no published studies have examined age differences in memory for incidentally encoded task-irrelevant emotional information, such as words in an emotional Stroop task. High arousal Low arousal .06 .05 .04 .03 Negativity effect in older adults: According to Mather and Knight (2005), positivity effects require cognitive control, and can be reversed by reducing older adults resources at encoding. Older adults' greater recall of negative over positive words in our study suggests that the emotional Stroop task (i.e., attend to color, inhibit irrelevant word) may limit older adults’ cognitive control resources. This depletion of their resources would impinge on their ability to fully implement their emotion regulation goals, which requires employing control mechanisms to inhibit automatically activated yet goal-inconsistent information (i.e., negative words). Chronic automatic activation of emotion regulation goals in older adults Utilization of available cognitive control resources, necessary to diminish negative information and enhance positive information Limited cognitive control resources (e.g., Divided Attention/Distraction) Age x valence interactions in memory No age x valence interactions in memory Mather & Knight (2005) 1. Both young and older adults show an emotional enhancement effect in memory for incidentally encoded words. 2. Both young and older adults show a negativity bias. The lack of positivity bias in older adults may due to the low level of cognitive resources as induced by the highly-demanding emotional Stroop task. .02 .01 .00 Negative Positive Neutral Negative Positive Neutral 1. Both young and older adults show better recall for emotional relative to neutral words that were incidentally encoded. 2. Older adults show a positivity bias in memory for incidentally encoded information. Low level of recall, particularly in older adults: Previous literature suggests that high resource demands of a modified Stroop task leads older adults to process task-irrelevant words in a shallower perceptual manner, which thus explains the lower subsequent explicit recall, particularly in older adults (Gopie, Craik, & Hasher, 2011). Young Older Three significant main effects: Neg>Pos>Neu (p < .001); YA>OA (p < .05); HA>LA (p < .05) Carstensen, L. L., & Mikels, J. A. (2005). At the intersection of emotion and cognition: Aging and the positivity effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 117-121. Mather, M., & Knight, M. (2005). Goal-directed memory: The role of cognitive control in older adults’ emotional memory. Psychology and Aging, 20, 554-570. This study is funded by the NSERC Discovery Grant awarded to Dr. Lixia Yang; the NSERC USRA Program and the Faculty of Arts URO program awarded to Dana Greenbaum. Please send correspondence to dgreenba@ryerson.ca