The African-American Freedom Movement Through

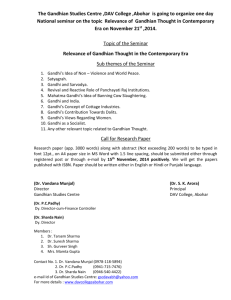

advertisement