“minor adjustments” and other not-so

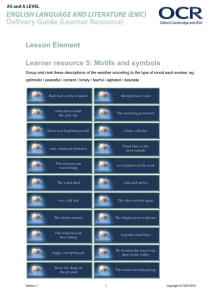

advertisement