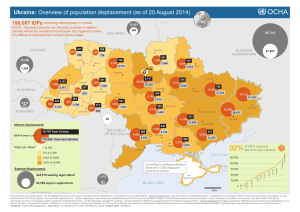

2016 GRID - The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre

advertisement