Neural

Networks

PERGAMON

Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

www.elsevier.com/locate/neunet

Contributed article

A new algorithm to design compact two-hidden-layer arti®cial neural

networks

Md. Monirul Islam, K. Murase*

Department of Human and Arti®cial Intelligence Systems, Fukui University, 3-9-1 Bunkyo, Fukui 910-8507, Japan

Received 25 August 2000; revised 19 March 2001; accepted 19 March 2001

Abstract

This paper describes the cascade neural network design algorithm (CNNDA), a new algorithm for designing compact, two-hidden-layer

arti®cial neural networks (ANNs). This algorithm determines an ANN's architecture with connection weights automatically. The design

strategy used in the CNNDA was intended to optimize both the generalization ability and the training time of ANNs. In order to improve the

generalization ability, the CNDDA uses a combination of constructive and pruning algorithms and bounded fan-ins of the hidden nodes. A

new training approach, by which the input weights of a hidden node are temporarily frozen when its output does not change much after a few

successive training cycles, was used in the CNNDA for reducing the computational cost and the training time. The CNNDA was tested on

several benchmarks including the cancer, diabetes and character-recognition problems in ANNs. The experimental results show that the

CNNDA can produce compact ANNs with good generalization ability and short training time in comparison with other algorithms. q 2001

Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Constructive algorithm; Pruning algorithm; Weight freezing; Generalization ability; Training time

1. Introduction

The automated design of arti®cial neural networks

(ANNs) is an important issue for any learning task. There

have been many attempts to design ANNs automatically,

such as various evolutionary and nonevolutionary algorithms (see Schaffer, Whitely & Eshelman, 1992, for a

review of evolutionary algorithms and Haykin, 1994, for a

review of nonevolutionary algorithms). The important parameters of any design algorithms are the consideration of

generalization ability and of training time of ANNs.

However, both parameters are controversial in many application areas; improving the one at the expense of the other

becomes a crucial decision (Jim, Giles & Horne, 1996).

The main dif®culty of evolutionary algorithms is that they

are quite demanding in both time and user-de®ned parameters (Kwok &Yeung, 1997a). In contrast, nonevolutionary algorithms require much smaller amounts of time and

user-de®ned parameters. The constructive algorithm is one

such nonevolutionary algorithm and it has many advantages

over other nonevolutionary algorithms (Kwok & Yeung,

1997a,b; Lehtokangas, 1999; Phatak & Koren, 1994). In

short, it starts with a minimal network (i.e. a network with

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 181-776-27-8774; fax: 181-776-27-8751.

E-mail address: murase@synapse.fuis.fukui-u.ac.jp (K. Murase).

minimal numbers of layers, hidden nodes, and connections)

and adds new layers, nodes, and connections as necessary

during training.

The most well-known constructive algorithms are the

dynamic node creation (DNC) (Ash, 1989) and the cascade

correlation (CC) algorithms (Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990).

The DNC algorithm constructs single-hidden-layer ANNs

with a suf®cient number of nodes in the hidden layer, though

such networks suffer dif®culty in learning some complex

problems (Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990). In contrast, the CC

algorithm constructs multiple-hidden-layer ANNs with one

node in each layer and is suitable for some complex

problems (Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990; Setiono & Hui,

1995). However, the CC algorithm has many practical

problems, such as dif®cult implementation in VLSI and

long propagation delay (Baluja & Fahlman, 1994; Lehtokangas, 1999; Phatak & Koren, 1994). In addition, the

generalization ability of a network may be degraded when

the number of hidden nodes N is large, because an N-th

hidden node may have some spurious connections (Kwok

& Yeung, 1997a).

This paper describes a new ef®cient algorithm, the

cascade neural network design algorithm (CNNDA), for

designing compact two-hidden-layer ANNs. It begins

network design in a constructive fashion by adding nodes

one after another. However, once the network converges, it

0893-6080/01/$ - see front matter q 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

PII: S 0893-608 0(01)00075-2

1266

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

starts pruning the network by deleting nodes and/or connections. In order to reduce hidden nodes fan-in and number of

hidden layers in ANNs, the CNNDA allows each hidden

layer of ANNs to contain several nodes that are automatically determined by its training process. A new training

approach, that temporarily freezes the input weights of a

hidden node when its output does not change much after a

few successive training cycles, is used in the CNNDA to

reduce training time.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 brie¯y

describes different training approaches used for designing

ANNs. Section 3 describes the CNNDA in detail and

describes the motivations and ideas behind various design

choices. Section 4 presents the experimental results of using

the CNNDA. Section 5 discusses various features of the

CNNDA. Finally, Section 6 gives a conclusion of this work.

2. Training methods for automated design of ANNs

One important issue with any design algorithm is the

method to use to train ANNs. While ANNs with ®xed architectures are trained only once, ANNs must be trained every

time their architectures are changed by design algorithms.

Hence, the computational ef®ciency of the training becomes

an important issue for any design algorithm. A large variety

of strategies exist whereby ANNs can be designed and

trained (see, for example, Haykin, 1994 and Hertz, Krogh

& Palmer, 1991, for nonevolutionary algorithms, Schaffer et

al., 1992 and Whitley, Starkweather & Bogart, 1990, for

evolutionary algorithms). In order to describe the training

process of the CNNDA, we brie¯y summarize two major

training approaches that are generally used by constructive

algorithms. One approach is to train all the nodes of an

ANN, and other is to train only the newly added hidden

node, keeping the previously added node's weights

unchanged.

The former training approach is very simple and straightforward; it optimizes all the weights (i.e. the whole network)

after each hidden node addition. Some constructive algorithms (Bartlett, 1994; Hirose, Yamashita & Hijiya, 1991;

Setiono & Hui, 1995), which are variants of the DNC algorithm (Ash, 1989), use this approach. The main disadvantage of this approach is that the solution space to be searched

becomes too large, resulting in a slower convergence rate

(Schmitz & Aldrich, 1999). It also suffers from the so-called

moving-target problem (Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990), where

each hidden node `sees' a constantly moving environment.

In addition, the training of the whole network becomes

computationally expensive as the network size becomes

larger and larger. In fact, small ANNs have been designed

using this approach in previous studies (Ash, 1989; Bartlett,

1994; Hirose et al., 1991; Setiono & Hui, 1995).

In the latter training approach, few weights are optimized

at a time, so that the solution space to be searched is reduced

and the computational burden is minimized. One such

approach is training only the newly added hidden node

and having training proceed in a layer-by-layer manner.

First, only the input weights of the newly added hidden

node are trained. After that, these weights are kept ®xed,

which is known as weight-freezing, and only the weights

connecting the hidden node to the output nodes are trained.

Algorithms in this training approach (Lehtokangas, 1999;

Phatak & Koren, 1994) are mostly variants of the CC algorithm (Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990). Although the convergence rate of this training approach is fast, as indicated by

Ash (1989), weight freezing during training of the newly

added hidden node does not ®nd the optimal solution. An

empirical study on the CC algorithm by Yang and Honavar

(1998) indicates that the impact of weight freezing on the

convergence rate, on the percentage of correctness in the

test set, and the network architecture produced is different

for different problem domains. Another study found that the

weight freezing of single-hidden-layer networks requires

large numbers of hidden nodes (Kwok & Yeung, 1993).

It, therefore, stands to reason that the bene®t of such

weight freezing is not conclusive; at the same time,

however, optimization of the whole network is computationally expensive and the convergence rate is slow. Therefore, a training approach that automatically determines

when and which node's input weights are to be frozen is

desirable. This training approach is, thus, a combination of

the two extremes: of optimizing all of the network weights

and of optimizing the weights of only the newly added node.

This is the training approach taken by the algorithm

proposed in this paper.

3. Cascade neural networks design algorithm (CNNDA)

In order to avoid the disadvantages of training either

whole network or only one node at a time, the CNNDA

adopts a training approach that temporarily freezes the

input weights of a hidden node when its output does not

change much in the next few training cycles. However,

the frozen weights may `unfreeze' in the pruning process

of the CNNDA. That is why the term `temporarily freeze',

rather than `freeze' is used in this study. It is shown by

example that when construction algorithms with backpropagation (BP) are used for network design, some hidden nodes

maintain an almost constant output after some training

cycles, while others change continuously.

In this study, the CNNDA is used to design two-hiddenlayered feedforward ANNs with sigmoid transfer functions.

However, it could be used to design ANNs with any number

of hidden layers, provided the maximum number of hidden

layers is prespeci®ed. Also, the nodes in hidden and output

layers could use any type of transfer functions. The feedforward ANNs considered by the CNNDA are generalized

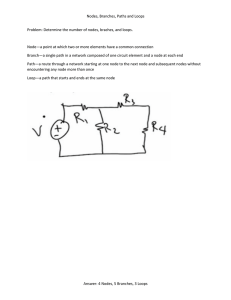

multilayer perceptrons (Fig. 1). In such architecture, the

®rst hidden (H1) layer receives only network inputs (I),

while the second hidden (H2) layer receives I plus the

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

1267

Fig. 1. A two-hidden-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP) network.

outputs (X) of the H1 layer. The output layer receives

signals from the H1 and H2 layers.

The major steps of the CNNDA can be described as

follows. Fig. 2 is a ¯ow chart of these steps.

Step 1 Create an initial ANN architecture. The initial

architecture has three layers, i.e. an input, an output,

and a hidden layer. The number of nodes in the input

and output layers is the same the number of inputs and

outputs of the problem. Initially, the hidden layer contains

only one node. Randomly initialize connection weights

between input layer to hidden layer and hidden layer to

output layer within a certain range.

Step 2 Train the network using the BP. Stop the training

process if the training error E does not signi®cantly

reduce in the next few iterations. The assumption is that

the network has inappropriate architecture. The training

error E is calculated according to the following equation

(Prechelt, 1994):

E 100

S X

N

omax 2 omin X

Yi

s 2 Zi

s2

NS

s1 i1

1

where omax and omin are the maximum and minimum

values of the target outputs in the problem representation,

N is the number of output nodes, S is the total number of

examples in the training set, Ys(s) and Zs(s) are, respectively, the actual and desired outputs of node i for training

data s. The advantage of the above error equation is that it

is less dependent on the size of the training set and the

number of output nodes.

Step 3 If the value of E is acceptable, go to step 12.

Otherwise, continue.

Step 4 Compute the number of hidden layers in the

network. If this number is two (i.e. the user-de®ned maximum-hidden-layer number), go to step 6. Otherwise,

continue.

Step 5 Create a new hidden layer, i.e. a second hidden (H2)

layer, with only one node. Initialize connection weights

of that node in the same way as described in step 1. Go to

step 2.

Step 6 Compute the contribution C and the number of fanin connections f of each node in the H2 layer. The Ci(n) of

the i-th node at any iteration n is Ei =E: Here Ei is the error of

the network excluding node i and computed according to

Eq. (1).

Step 7 Compare the values of Ci

n and fi

n with their

previous values Ci

n 2 t1 and fi

n 2 t1 ; respectively. If

Ci

n # Ci

n 2 t1 and fi

n 2 fi

n 2 t1 M, continue.

Otherwise, go to step 9. Here t 1 and M are user-de®ned

positive integer numbers.

Step 8 Freeze the fan-in capacity of the i-th node. That

means the i-th node will not receive any new input signals

in the future when new nodes are added in the H1 layer.

Notice that generally the i-th node and all other nodes in the

H2 layer receive signals from all nodes in the H1 layer.

Mark the i-th node with F.

Step 9 Compare the output X(n) of each node in the H1

layer and F marked nodes in the H2 layer with their previous

values X(n 2 t 2). Here t 2 is the user-de®ned positive integer number. If X

n . X

n 2 t2 , continue. Otherwise, go

to step 11.

Step 10 Temporarily freeze input connection weights,

keeping weight values ®xed for some time, for any nodes

in the H1 layer and F marked nodes in the H2 layer whose

X

n . X

n 2 t2 .

Step 11 Add one node in the H1 or H2 layer. If adding a

node in the H1 layer produces a larger size ANN (in terms of

connections) than does adding a node in the H2 layer, then

add one node in the H1 layer. Otherwise, add one node in the

H2 layer. In the CNNDA, the addition of a node in any layer

is done by splitting an existing node in that layer using the

method by Odri, Petrovacki and Krstonosic (1993). Go to

step 2.

Step 12 According to contribution C, delete the least

contributory node from the network and unfreeze the

1268

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

Fig. 2. Flow chart of the CNNDA.

input connections (if any connections are frozen) of

one hidden node. Train the pruned network by the

BP. If the network converges again, delete one

node and unfreeze the input connections of one

node. Continue this process until the network no

longer converges.

Step 13 Decide the number of connections to be

deleted by generating a random number between 1

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

1269

Fig. 3. A two-hidden-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP) network with frozen input connection weights of some hidden nodes. I and X represent the input to the

network and the output of a hidden node, respectively. w represents the connection weight.

and the user-de®ned maximum number. Calculate the

approximate importance of each connection in the

network by the nonconvergent method (Finnoff,

Hergent & Zimmermann, 1993). According to calculated importance, delete a certain number of connections and unfreeze the same number of connections (if

any connections are frozen) from the network. Train

the pruned network by the BP. Continue this process

until the network no longer converges. The last

network before converge ends is the ®nal network.

This design procedure seems rather complex compared

to the simple constructive algorithms (e.g. Ash, 1989;

Bartlett, 1994; Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990) that have

only one component, i.e. node addition. However, the

essence of the CNNDA is the use of ®ve components:

freezing fan-in capacity, temporary weight freezing, node

addition by node splitting, selective nodes and/or connections deletion.

3.1. Freezing the fan-in capacity of a hidden node

The use of freezing a hidden node's fan-in capacity in the

CNNDA re¯ects this algorithm's emphasis on the generalization ability of the network. It also re¯ects the CNNDA's

emphasis on computational ef®ciency and training time.

Freezing the fan-in capacity of a node in the H2 layer is

necessary, since it would otherwise be impossible to freeze

the input connection weights of that node due to the type of

ANN architecture (Fig. 1) and the training concept used in

the CNNDA. Restricted fan-in is known to improve the

generalization ability (Lee, Bartlett & Williamson, 1996),

and weight freezing is known to reduce the training time and

computational cost of ANNs (Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990;

Kwok & Yeung, 1997a,b).

In order to freeze the fan-in capacity of the i-th node in

the H2 layer, the CNNDA compares the i-th node's contri-

bution Ci

n and the number of fan-in connections fi

n at

iteration n with their previous values Ci

n 2 t1 and fi

n 2

t1 ; respectively. As mentioned previously, the contribution

of the i-th node is the ratio of network errors, i.e. Ei =E, where

Ei is the error of the network excluding node i and is

computed according to Eq. (1). Here, it is worth mentioning

that the computation of Ei does not require any extra computational cost because Ei is part of E. Thus, one could extract

the value of Ei from E during its computation and save it for

future use. In the CNNDA, if Ci

n # Ci

n 2 t1 and fi

n 2

fi

n 2 t1 M; the assumption is that increasing fan-in and

further training does not improve the i-th node's contribution. Therefore, the CNNDA freezes the fan-in capacity of

the i-th node and marks it with F.

3.2. Temporary weight freezing (TWF)

This section describes the temporary weight freezing

technique used in the CNNDA. As mentioned previously,

the training approach of the CNNDA temporarily freezes

the input weights of a hidden node when its output does not

change much over the next few training cycles. However,

the CNNDA may unfreeze the frozen weights in the pruning

process of a network. The pruning of nodes and/or connections from a trained network increases bias (i.e. error) and

reduces variance (i.e. number of adjustable weights) of the

pruned network. In contrast, the unfreeze of frozen weights

increases variance of the pruned network. Thus, unfreezing

balances between bias and variance of the pruned network.

It is known that balancing between bias and variance

improves the approximation capability of the network

(Geman & Bienenstock, 1992) and increasing variance

improves the convergence rate (Kwok & Yeung, 1997a).

The temporary weight freezing is applied to any nodes in

the H1 layer and only F marked nodes in the H2 layer. In the

case of F marked nodes, the temporary weight freezing is

not straightforward like nodes in the H1 layer. This is

1270

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

because the output of any F marked node depends not only

the original network input I but also on the output X of the

H1 layer (Fig. 1). However, the output of any node in the H1

layer depends only on I (Fig. 1). In fact, a problem arises

when the output Xj of the j-th node in the H1 layer is not

constant due to its unfrozen input weights. However, the

CNNDA intends to freeze the input connection weights of

any F marked node i (Fig. 3).

In order to ensure a constant amount of signal for node i

from node j, the CNNDA implements the following steps

for any node i. (a) Save Xj

n and wij(n) when input weights

of a node i are going to be frozen at iteration n. Here wij is

the connection weight between nodes i and j. (b) According

to the following equation, change the value of wij

n when

the value of Xj

n changes in future training cycles.

Xj

nwij

n

wij

n 1 1

Xj

n 1 1

2

The implementation of Eq. (2) ensures that the i-th node will

always receive a constant amount of signal from the j-th

node in spite of its variable output. However, the CNNDA

stops the implementation of Eq. (2) whenever the input

weights of the j-th node are frozen.

3.3. Node addition

In this section, the node addition process of the CNNDA

has been described. In the CNNDA, each new node to be

added into any hidden layer of an ANN is implemented by

splitting an existing node (possibly with unfrozen connections) of that layer. The process of a node splitting is known

as `cell division' (Odri et al., 1993). Two nodes created by

splitting an existing node have the same number of connections as the existing node. The weights of the new nodes are

calculated according to Odri et al. (1993) and are given

below.

w1ij

1 1 bwij

3

w2ij 2bwij

4

where w represent the weight vector of the existing node, w 1

and w 2 are the weight vectors of the new nodes. b is the

mutation parameter whose value may be either a ®xed or

random value. The advantage of this addition process is that

it does not require random initialization for the weight

vector of the new added node. Thus, the new ANN can

strongly maintain the behavioral link with its predecessor

(Yao & Liu, 1997).

3.4. Connection deletion

As mentioned previously, the CNNDA deletes few

connections (according to a user-de®ned number) selectively, rather than randomly. The choice of connections to

be deleted is determined by their importance in the network.

In this study, the importance of each connection is deter-

mined by the nonconvergent method (Finnoff et al., 1993).

In this method, the importance of a connection is de®ned by

a signi®cance test for its weight's deviation from zero in the

weight update process. Consider the weight update Dwij

2hdEs =dw

of linear error function

P ij ;Pby the local gradient

E E Ss1 Ni1 uYi

s 2 Zi

su with respect to sample s

and weight wij. The signi®cance of the deviation of wij from

zero is de®ned by the test variable as follows (Finnoff et al.,

1993):

S

X

zsij

s1

test

wij s

S

P s

z 2 z ij 2

s1

5

ij

where zsij wij 1 Dwsij ; z ij represent the average over the set

zsij ; s 1; ¼; S: A small value of test

wij indicates the less

importance of the connection with weight wij : The advantage of this method is that it does not require any extra

parameter for determining the importance of a connection.

4. Experimental studies

We have selected the most well known benchmarks to

test the CNNDA described in the previous section. These

benchmarks are the cancer, diabetes and character-recognition problems. The data sets representing all these problems

were real-world data and were obtained from the UCI

machine learning benchmark repository.

In order to assess the effects of weight freezing on

network performance, two sets of experiments were carried

out. In the ®rst set of experiments, the CNNDA with weight

freezing, described in Section 3, was applied. The CNNDA

without weight freezing was applied in the second set of

experiments.

In all experiments, one bias unit with a ®xed input 1 was

used for hidden and output layers. The learning rate was set

between [0.1, 1.0] and the weights were initialized to

random values between [21.0, 1.0]. To ensure fairness

across all the experiments, each experiment was carried

out 30 times. The results presented in the following sections

are the average of these 30 runs.

4.1. The breast cancer problem

This problem has been the subject of several studies on

network design (e.g. Setiono & Hui, 1995; Yao & Liu,

1997). The data set representing this problem contained

699 examples. Each example consisted of nine-element

real valued vectors. This was a two-class problem. The

purpose of this problem was to diagnose a breast tumor as

either benign or malignant.

4.2. The diabetes problem

Due to a relatively small data set and high noise level, the

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

1271

Table 1

Performance of the CNNDA in terms of network architectures and generalization ability

CNNDA

Cancer

Without weight freezing

With weight freezing

Diabetes

Without weight freezing

With weight freezing

Character

Without weight freezing

With weight freezing

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Mean

Mean

Min

Max

Number of hidden nodes

Number of connections

Classi®cation error

3.4

3

5

3.5

3

5

4.3

3

5

4.3

3

5

20.0

12

25

19.8

12

24

38.3

27

36

35.8

28

39

39.8

30

54

40.4

27

50

851.3

516

1068

844.5

523

1040

0.0116

0.0000

0.0171

0.0115

0.0000

0.0171

0.2087

0.1979

0.2135

0.1991

0.1875

0.2083

0.2471

0.1910

0.2937

0.2344

0.1830

0.2807

Table 2

Performance of the CNNDA in terms of the number of epochs, computational cost, and training time. Note that computational cost is represented by the number

of weight updates

Number of epochs

Cancer

Without weight freezing

With weight freezing

Diabetes

Without weight freezing

With weight freezing

Character

Without weight freezing

With weight freezing

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

Mean

Min

Max

diabetes problem is one of the most challenging problems in

machine learning (Yao & Liu, 1997). This was a two-class

problem in which individuals were diagnosed as either positive or negative for diabetes based on patients' personal

data. There were 768 examples in the data set, each of

which consisted of eight-element real valued vectors.

4.3. The character-recognition problem

Since all the above-mentioned problems were small classi®cation problems, we chose character recognition as a

large problem for assessing the performance of the

CNNDA for a large problem. The data set representing

499.1

456

649

451.6

390

589

335.4

265

410

261.7

215

329

6911.4

6410

7339

5913.5

5214

6391

Computational cost

5

115.67 £ 10

111.85 £ 10 5

125.50 £ 10 5

89.67 £ 10 5

82.97 £ 10 5

98.86 £ 10 5

61.5 £ 10 5

43.2 £ 10 5

93.5 £ 10 5

48.11 £ 10 5

33.44 £ 10 5

78.5 £ 10 5

25.31 £ 10 8

18.31 £ 10 8

36.31 £ 10 8

22.11 £ 10 8

16.62 £ 10 8

28.31 £ 10 8

Training time (s)

28.3

22

34

22.5

18

28

18

12

25

14

9

19

4537

4210

4815

3902

3414

4218

this problem contained 20,000 examples. This was a 26class problem. The purpose of this problem was to classify

digitized patterns. The inputs were 16-element real valued

vectors. Elements of the input vector were numerical attributes computed from a pixel array containing the characters.

4.4. Experiment setup

In this study, all data sets representing the problems are

divided into two sets. One is the training set and the other is

the test set. Note that no validation set is used in this study.

The numbers of examples in the training set and test set are

based on numbers in other works, in order to make

1272

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

Table 3

Connection weights and biases (represented by B) of the best network (shown in Fig. 4) produced by the CNNDA for the diabetes problem

H11

H11

H21

H22

O11

O12

24.06

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

4.43

21.57

29.34

22.64

22.78

26.05

23.06

212.58

24.76

2.89

3.13

1.38

20.78

21.63

H11

22.40

2.40

H12

21.50

2.45

H22

22.94

2.94

B

1.84

21.75

0.85

8

29.99

2.21

B

11.68

2.53

20.73

² Diabetes data set: the ®rst 384 examples are used for the

training set and the last 192 for the test set.

² Character data set: 1000 randomly selected examples

are used for the training set, and 4000 randomly selected

examples are used for the test set.

4.5. Experimental results

Fig. 4. The network design process of the CNNDA for the diabetes

problem: (a) network at step 1; (b) network at step 12; (c) ®nal network.

comparison with those works possible. The sizes of the

training and test data sets used in this study are given as

follows.

² Breast cancer data set: the ®rst 349 examples are used

for the training set and the last 175 for the test set.

Tables 1±3 show the experimental results of the CNNDA

for the cancer, diabetes and character-recognition problems.

The classi®cation error in Table 1 refers to the percentage of

wrong classi®cations in the test set. The computational cost

refers to the total number of weight updates by BP for the

whole training period. The training time is the amount of

CPU time required for training. It was measured in seconds,

on an IBM PC 300GL (Pentium II, 200 MHz) running Red

Hat Linux Version 6.0.

It is seen that the CNNDA requires a small number of

training cycles to produce compact ANNs with small classi®cation errors. For example, the CNNDA with weight

freezing produces an ANN with three hidden nodes that

achieves a classi®cation error of 18.75% for the diabetes

problem. Fig. 4 shows the design process of this network

and Table 3 its weights. It is interesting to see that the

deletion process not only helps the CNNDA produce a

compact network, but also changes the position of a hidden

node from second hidden layer to ®rst hidden layer. That is,

because the second layer is also connected to the input layer

in this network structure, if the connection from the ®rst

layer is deleted, then the second layer is equal to the

®rst layer, but nodes of the ®rst layer do not move to

the second layer. This demonstrates that, if necessary, the

deletion process could change a two-hidden-layer network

into one with a single-hidden-layer.

In order to show how a hidden node's output changes in

the whole training period, Figs. 5 and 6 show the hidden

node's output for the cancer and diabetes problems. It is

seen that some hidden nodes maintain almost constant

output after some training epochs, while others change

continuously. This phenomenon illustrates that one could

freeze the input weights of a hidden node when its output

does not change much over the next few training epochs,

thereby reducing the computational cost. Figs. 7 and 8 show

the effects of such weight freezing on the network error for

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

1273

Fig. 5. The hidden nodes output of a network (9±2±2±2) for the cancer problem: (a) without weight freezing; (b) with weight freezing.

Fig. 6. The hidden nodes output of a network (8±1±2±2) for the diabetes problem: (a) without weight freezing; (b) with weight freezing.

Fig. 7. The error of a network (9±2±2±2) for the cancer problem: (a) without weight freezing; (b) with weight freezing.

the cancer and diabetes problems, respectively. It is

observed that weight freezing makes for faster convergence (Figs. 7 and 8) and lower computational cost than

without it (Table 2). Thus, weight freezing reduces the

training time in designing ANNs (Table 2). Table 4

shows the effect of unfreezing on convergence rate in

CNNDA. It is seen that unfreezing has a more

pronounced effect on a large classi®cation problem

than on those of a small classi®cation problem. Because

a large classi®cation problem (e.g. character recognition) requires many hidden nodes (Table 1) it may

require many deletion processes.

1274

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

Fig. 8. The error of a network (8±1±2±2) for the diabetes problem: (a) without weight freezing; (b) with weight freezing.

Table 4

Effect of weight unfreezing in CNNDA

Number of epochs by CNNDA

Without weight unfreezing With weight unfreezing

Cancer

Mean 467.8

Min

409

Max

610

Diabetes Mean 277

Min

229

Max

346

Character Mean 6538.1

Min

5926

Max 6912

451.6

390

589

261.7

215

329

5913.5

5214

6391

4.6. Comparison

In this section, we compare the results of the CNNDA

(with weight freezing) with the results of other works. Yao

and Liu (1997) have reported a new evolutionary system

called EPNet in designing ANNs for the cancer problem.

The training algorithm used in EPNet is BP with an adaptive

learning rate. In order to improve generalization ability,

EPNet uses a validation set (consisting of 175 samples)

for calculating a network error, although a training set

(consisting of 349 samples) is used for training. Employing

the constructive approach with a quasi-Newton method for

training, Setiono and Hui (1995) proposed a new algorithm

(FNNCA) in designing ANNs for the cancer problem. The

number of training samples used in the FNNCA is 524.

Prechelt (1994) also reported results of manually designed

ANNs (denoted as MDANN) for the cancer problem. Like

EPNet, MDANN uses a validation set (consisting of 175

samples) along with a training set (consisting of 349

samples) for improving generalization ability.

To make comparison possible with CC like algorithm, we

applied the modi®ed cascade correlation algorithm

(MCCA), proposed by Phatak and Koren (1994), to the

cancer and character-recognition problems. We chose the

MCCA because the network architecture produced by

MCCA was very similar to that of CNNDA. Like

CNNDA, MCCA allows each hidden layer to contain

several nodes. However, the number of nodes in each

hidden layer of the MCCA was user-de®ned. The MCCA

produced strictly layered network architectures, i.e. each

layer received signals only from its previous layer. For

making fair comparison, the training algorithm used in

this study was a BP, although Phatak and Koren (1994)

used a quick-prop training algorithm. The number of training and test samples used in MCCA was similar to that of

CNNDA.

Table 5 compares the results among the CNNDA,

MCCA, FNNCA, MDANN and EPNet for the cancer

problem. The best classi®cation accuracy of produced

ANNs by MCCA and FNNCA were 0.0115 and 0.0145,

respectively. Prechelt (1994) tried different ANNs manually

for the problem and found a best classi®cation error of

0.0115 by a six-hidden-node ANN. In terms of average

results, EPNet found two-hidden-node ANNs with a classi®cation error 0.01376, while the CNNDA achieved a classi®cation error of 0.0115 for a network having 3.5 hidden

nodes on average. Here it is important to note that the

CNNDA achieves a lower classi®cation error without

using a validation set and also using a small number of

training samples. The smaller number of hidden nodes

required by EPNet could be attributed to the type of ANN

architecture used by EPNet; however, the number of

connections of the network produced by CNNDA is very

competitive with that of EPNet. Speci®cally, given the same

number of hidden nodes, the network architecture used in

EPNet had more connections than that of CNNDA. In terms

of training epochs, the best performance of MCAA was 403

epochs, while CNNDA required 451.6 epochs on average.

EPNet required 109,000 epochs for a single run.

Table 6 compares the average classi®cation error of

CNNDA with EPNet (Yao & Liu, 1997) and other works

(Michie, Spiegelhalter & Taylor, 1994) on the diabetes

problem. It was found that the CNNDA outperformed

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

1275

Table 5

Comparison among CNNDA (with weight freezing), MCCA (Phatak & Koren, 1994), FNNCA (Setiono & Hui, 1995), MDANN (Prechelt, 1994), and EPNet

(Yao & Liu, 1997) in terms of network size, classi®cation accuracy, and number of epochs for the cancer problem

Number of hidden nodes

Number of connections

Classi®cation error

Number of epochs

a

Best results

by MCCA in

®ve runs

Best results

by FNNCA

in 50 runs

Best results

by MDANN

Average results

over 30 runs

by EPNet

Average results

over 30 runs

by CNNDA

4

50

0.0115

403

3

±a

0.0145

±

6

±

0.0115

75

2.0

41.0

0.01376

109,000

3.5

35.8

0.0115

451.6

`± ' means not available.

Table 6

Comparison among CNNDA (with weight freezing), EPNet (Yao & Liu, 1997), and others (Michie et al., 1994) in terms of average classi®cation error for the

diabetes problem

Algorithm

CNNDA

Classi®cation error 0.199

a

EPNet

Logdisc a DIPOL92 a

Discrim a SMART a

RBF a

ITrule a

BP a

Cal5 a

CART a

CASTLE a

Quadisc a

0.224

0.223

0.225

0.243

0.245

0.248

0.250

0.255

0.258

0.262

0.224

0.232

Reported in Yao and Liu (1997).

Table 7

Comparison among CNNDA, modular network (Anand et al., 1995) and nonmodular network (Anand et al., 1995) in terms of network size, classi®cation

accuracy, and number of epochs for the character-recognition problem

Number of hidden nodes

Classi®cation error

Number of epochs

Best

results by

MCCA in

®ve runs

Average results

over ®ve runs by

modular network

Average results over

®ve runs by

nonmodular network

Average

results

over 30

runs by

CNNDA

36

0.2687

7013

15

0.25

5520

15

0.256

7674

19.8

0.23

5913.5

EPNet and all the other works. To achieve this rate of classi®cation error, CNNDA and EPNet use the same number of

training samples. However, EPNet uses a validation set

consisting of 192 samples for improving classi®cation accuracy. Because data from medical domains are often very

costly to obtain, it would be very dif®cult to use a validation

set for improving classi®cation accuracy. We believe that

the classi®cation performance of the CNNDA would be

much better if we were to use a validation set. On the

other hand, the results represented in Michie et al. (1994)

were the average results of the best 11 experiments out of

23. In terms of network size, the average number of connections and hidden nodes of produced ANNs by the CNNDA

were 4.2 and 33.0, respectively, while they were 3.4 and

52.3 for EPNet. The convergence rate of the CNNDA for

producing ANNs is much faster, requiring only 235 epochs,

compared to that of EPNet, which requires 109,000 epochs

for a single run.

Anand, Mehrotra, Mohan and Ranka (1995) reported results

for the character-recognition problem using ®xed network

architecture. They used two types of ®xed architecture with

15 hidden nodes. One is modular architecture and the other is

nonmodular architecture. The standard BP is used for training

of nonmodular architecture, while modi®ed BP, which is faster

than standard BP by one order of magnitude (Anand et al.,

1995), is used for modular architecture. The classi®cation

error and number of epochs by the modular network were

0.25 and 5520, respectively, while nonmodular network

required 7674 epochs to achieve a classi®cation error of

0.26. In terms of best result, MCCA achieved a classi®cation

error of 0.2687 for a network having 36 hidden nodes by using

7013 training epochs. The CNNDA achieves an average classi®cation error of 0.23 using a network with 19.8 hidden nodes.

It requires 5913.5 epochs on average for a single run. Here, it is

worth mentioning that the performance of Anand et al. was an

average of ®ve runs, while it was an average of 30 runs for the

CNNDA. We think that the results of CNNDA would be much

better if we took an average of ®ve runs and we would use

modi®ed BP. Table 7 summarizes the above results.

5. Discussion

Although there have been many attempts to create the automatic determination of single-hidden-layer network architecture, few have been attempted for multiple-hidden-layer

1276

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

networks (see, for example, a review paper by Kwok and

Yeung, 1997a, for nonevolutionary algorithms and Whitley

et al., 1990, for a study on evolutionary algorithms). It is

known that multiple-hidden-layer ANNs are suitable for

complex problems (Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990; Setiono &

Hui, 1995) and are superior to single-hidden-layer networks

(Tamura & Tateishi, 1997). In this study, we have proposed

an ef®cient algorithm (CNNDA) for designing compact

two-hidden-layer networks. The salient features of the

CNNDA are use of a constructive pruning strategy, node

addition by node splitting, freezing a hidden node's fan-in,

and temporary weight freezing. In this section, we discuss

each of these features with respect to classi®cation accuracy, training time or both.

It is known that constructive algorithms in some cases might

produce larger sized networks than necessary (Hirose et al.,

1991), and that pruning algorithms are computationally expensive (Lehtokangas, 1999). Network size and computational

expense affect classi®cation accuracy and training time,

respectively. Thus, the synergy between constructive and

pruning algorithms is suitable for producing compact

networks at a reasonable computational expense. The use of

pruning algorithms in conjunction with constructive algorithms not only reduces the network size (in terms of hidden

nodes and/or connections), but also changes the position of a

node from one hidden layer to another (Fig. 4). In this case, the

reduction of size improves the classi®cation accuracy by about

7.69%. Most importantly, the connection pruning might

change two-hidden-layer networks into single-hidden-layer

networks. In other words, the connection pruning could

convert complex networks into simple networks. The node

pruning in the CNNDA allows users to add multiple nodes

rather than one node in the node addition process. In such a

case, the convergence will be fast.

The constructive pruning strategy used in the CNNDA is

similar to the one proposed by Hirose et al. (1991) for

designing single-hidden-layer networks. However, the

approaches used in the CNNDA for network construction

and pruning are different from those used in Hirose et al.

(1991) and other works (e.g. Ash, 1989; Fahlman & Lebiere,

1990). Unlike other studies on network design (e.g. Ash,

1989; Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990; Hirose et al., 1991), the

CNNDA adds a node through splitting an existing hidden

node. The addition of a node by splitting an existing node

has many advantages over random addition (Odri et al.,

1993; Yao & Liu, 1997). In addition, adding a node by

splitting an existing node could be seen as the deletion of

one node and the addition of two nodes. It has been shown

that in terms of network performance, adding multiple

hidden nodes is better than adding the same number of

nodes one by one (Lehtokangas, 1999).

In the pruning process, the CNNDA deletes nodes and/or

connections selectively rather than randomly. The advantage of selective deletion is that it can preserve those

nodes and/or connections that are important for network

performance. This view is supported by Giles and Omlin

(1994). They propose a simple pruning method, in which a

state neuron with small incoming weights is considered less

important, for improving classi®cation accuracy of recurrent neural networks. They found that selective pruning is

better than random pruning and weight decay.

Freezing of a hidden node's fan-in and allowing many

nodes in each hidden layer make the CNNDA suitable for

producing ANNs with bounded fan-in of the hidden nodes.

It is known that a network with bounded fan-in is ef®ciently

learnable and is suitable for hardware implementation of

ANNs (Lee et al., 1996; Phatak & Koren, 1994). In order

to reduce the fan-in of the hidden node, Phatak and Koren

(1994) modi®ed the CC algorithm by allowing more than

one node in each hidden layer. The fan-in of the hidden node

is, thus, controlled by the number of nodes allowed in each

hidden layer. The maximum number of nodes allowed in

each hidden layer is determined by the user-de®ned parameter (Phatak & Koren, 1994). As pointed out by Kwok and

Yeung (1997a), this number is very crucial for network

performance. Restricting this number to a small value limits

the ability of the hidden nodes to form complicated feature

detectors (Kwok & Yeung, 1997a). In contrast, the training

process of the CNNDA automatically determines the

number of nodes in the hidden layer. As mentioned in

Section 3.1, the freezing fan-in helps the CNNDA freeze

input weights of nodes in the second hidden layer. It is

known that weight freezing reduces the computational

expense and training time (Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990;

Kwok & Yeung, 1997a,b; Lehtokangas, 1999; Phatak &

Koren, 1994). In this sense, freezing fan-in reduces computational expense and training time.

Training time, which is composed of the convergence rate

(epoch) and the computational expense, is a limiting factor

in the practical application of ANNs to many problems

(Battiti, 1992). Our experimental results show that when

BP is used as a training algorithm in designing ANNs,

some nodes of ANNs maintain almost a constant output

after a training period (Figs. 5 and 6). In other words, the

input connection weights of those nodes are automatically

®xed. This implies that one could freeze those nodes for

reducing the computational expense, which is directly

proportional to the number of weights updated by BP

(Battiti, 1992). In order to reduce the computational

expense, the CNNDA, thus, freezes the input weights of a

hidden node when its output does not change much in the

next few training cycles. However, the frozen weights may

unfreeze in the pruning process of the CNNDA.

The weight freezing in the CNNDA not only reduces the

computational cost (Table 2) but also improves the convergence rate (Figs. 7 and 8). One reason of convergence

improvement due to weight freezing is that it can overcome

the `moving target problem' where nodes in the hidden

layers of the network `see' a constantly shifting picture as

both the upper and lower hidden layers' nodes evolve (Fahlman & Lebiere, 1990; Schmitz & Aldrich, 1999). That is,

consider two computational sub-tasks, X and Y, that must be

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

performed by the hidden nodes in a network. If task X

generates a larger or more coherent error signal than task

Y, there is a tendency for all the nodes to concentrate on X

and ignore Y. Once problem X is solved, the nodes then see

task Y as the remaining source of error. However, if they all

begin to move toward Y at once, problem X reappears. It is

known that this problem arises in the earlier part of the

training process and makes it impossible for such nodes to

move decisively toward a good solution (Fahlman &

Lebiere, 1990). The combined effect of computational

cost and convergence rate reduces the training time

(Table 2).

It is also seen that temporary weight freezing in CNNDA

improves the classi®cation accuracy of the test set (Table 1).

There may be two reasons for such improvement: one is the

reduction of training time; and the other is the balancing

between bias (i.e. error) and variance (i.e. number of adjustable weights) in the training process. It is known that long

training time makes a network specialization on the training

set which in turn reduces the classi®cation accuracy of the

test set. Thus, the reduction of training time may improve

the classi®cation accuracy of the test set. The temporary

weight freezing in the CNNDA not only reduces the training

time but also balances between bias and variance in the

training process of the network. For example, when the

training is progressed, the bias of the network is decreased,

however, the variance is the same or increased as nodes are

added. Thus, the weight freezing in the training process

balances between bias and variance. It is known that balancing between bias and variance improves the approximation

capability of the network (Geman & Bienenstock, 1992).

A closely related idea of using weight freezing in network

training was ®rst studied by Fahlman and Lebiere (1990).

They found that while weight freezing improves the convergence rate, its effect on classi®cation accuracy is not known.

In their freezing technique, two cost functions are required,

one for network training and another for weight freezing.

Thus, stochastic gradient methods could not be applied in

their training method, although they are suitable for large

problems (Bourlard & Morgan, 1994; Lehtokangas, 1999).

Their freezing technique also requires that a pool of eight

nodes be trained, from which the best node is added to the

network and its weights are frozen (Fahlman & Lebiere,

1990). However, the training of eight nodes for the freezing

of one node's weights is computationally expensive, especially for large ANNs. In the CNNDA, the temporary weight

freezing does not require any cost function or the training of

a pool of nodes.

Our simulation results have demonstrated the effectiveness of the CNNDA for producing compact ANNs with high

classi®cation accuracy and a short training cycle. In its

current implementation, the CNNDA has been applied to

design two-hidden-layer ANNs. It would be interesting to

apply the CNNDA to the design of more complex networks

in which the number of hidden layers is more than two and

unknown. In such cases, an important improvement to the

1277

CNNDA would be to make the determination of the number

of hidden layers adaptive like the CC algorithm. It would be

interesting to see whether or not the temporary weight freezing technique used in the CNNDA is applicable to other

training algorithms such as the quasi-Newton method

(Setiono & Hui, 1995).

6. Conclusions

We have proposed an ef®cient algorithm (CNNDA)

for designing compact two-hidden-layer feedforward

ANNs. The novelty of the CNNDA is that it can determine the number of nodes in each hidden layer automatically and, if necessary, it can reduce a two-hiddenlayer network to a single-layer network. By analyzing a

hidden node's output, a new temporary weight freezing

technique has been introduced in the CNNDA. The

experimental results for the cancer, diabetes and character-recognition problems show that temporary weight

freezing not only reduces the training time, but also the

classi®cation error. However, further investigation is

necessary to draw any conclusion about the effect of

weight freezing on classi®cation error. It is found that

ANNs produced by the CNNDA are smaller in size and

have a lower rate of classi®cation error than other

evolutionary and nonevolutionary algorithms. The

CNNDA requires much smaller number of training

epochs than do evolutionary algorithms in designing

ANNs.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers

for their constructive comments which helped to

improve the clarity of this paper greatly. They also

wish to thank Drs X. Yao, N. Kubota and T. Asai for

their helpful discussions. This work was supported by

the Arti®cial Intelligence Research Promotion Foundation, Nagoya, Japan.

References

Anand, R., Mehrotra, K., Mohan, C., & Ranka, A. (1995). An ef®cient

neural algorithm for the multiclass problem. IEEE Transactions on

Neural Networks, 6, 117±124.

Ash, T. (1989). Dynamic node creation in backpropagation networks.

Connnection Science, 1, 365±375.

Baluja, S., & Fahlman, S. E. (1994). Reducing network depth in the

cascade-correlation learning architecture. Technical Report CMUCS-94-209, Carnegie Mellon University.

Bartlett, E. B. (1994). Dynamic node architecture learning: an information

theoretic approach. Neural Networks, 7, 129±140.

Battiti, R. (1992). First- and second-order methods for learning: between

steepest descent and Newton's method. Neural Computation, 4, 141±

161.

Bourlard, H., & Morgan, N. (1994). Connectionist speech recognitionÐa

hybrid approach, Boston: Kluwer Academic.

1278

Md.M. Islam, K. Murase / Neural Networks 14 (2001) 1265±1278

Fahlman, S. E., & Lebiere, C. (1990). The cascade-correlation learning

architecture. In D. S. Touretzky, Advances in neural information

processing systems 2 (pp. 524±532). San Mateo, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Finnoff, W., Hergent, F., & Zimmermann, H. G. (1993). Improving model

selection by nonconvergent methods. Neural Networks, 6, 771±783.

Geman, S., & Bienenstock, E. (1992). Neural networks and the bias/

variance dilemma. Neural Computation, 4, 1±58.

Giles, C. L., & Omlin, C. W. (1994). Pruning recurrent neural networks for

improved generalization performance. IEEE Transactions on Neural

Networks, 5, 848±851.

Haykin, S. (1994). Neural networks: a comprehensive foundation, New

York: Macmillan College Publishing Company.

Hertz, J. K., Krogh, A., & Palmer, R. G. (1991). Introduction to the theory

of neural computation, Redwood City, CA: Addison-Wesley.

Hirose, Y., Yamashita, K., & Hijiya, S. (1991). Backpropagation algorithm

which varies the number of hidden units. Neural Networks, 4, 61±66.

Jim, K., Giles, C. L., & Horne, B. G. (1996). An analysis of noise in

recurrent neural networks: convergence and generalization. IEEE

Transactions on Neural Networks, 7, 1424±1438.

Kwok, T. Y., & Yeung, D. Y. (1993). Experimental analysis of input weight

freezing in constructive neural networks. In Proc. IEEE International

Conference on Neural Networks (pp. 511±516). San Francisco, CA.

Kwok, T. Y., & Yeung, D. Y. (1997a). Constructive algorithms for structure

learning in feedforward neural networks for regression problems. IEEE

Transactions on Neural Networks, 8, 630±645.

Kwok, T. Y., & Yeung, D. Y. (1997b). Objective functions for training new

hidden units in constructive neural networks. IEEE Transactions on

Neural Networks, 8, 1131±1148.

Lee, W. S., Bartlett, P., & Williamson, R. C. (1996). Ef®cient agnostic

learning of neural networks with bounded fan-in. IEEE Transactions

on Information Theory, 42, 2118±2132.

Lehtokangas, M. (1999). Modeling with constructive backpropagation.

Neural Networks, 12, 707±716.

Michie, D., Spiegelhalter, D. J., & Taylor, C. C. (1994). Machine learning,

neural and statistical classi®cation, London: Ellis Horwood Limited.

Odri, S. V., Petrovacki, D. P., & Krstonosic, G. A. (1993). Evolutional

development of a multilevel neural network. Neural Networks, 6,

583±595.

Phatak, D. S., & Koren, I. (1994). Connectivity and performance tradeoffs

in the cascade correlation learning architecture. IEEE Transaction on

Neural Networks, 5, 930±935.

Prechelt, L. (1994). PROBEN1Ða set of benchmarks and benchmarking

rules for neural network training algorithms. Technical Report 21/94,

Faculty of Informatics, University of Karlsruhe, Germany.

Schaffer, J. D., Whitely, D., & Eshelman, L. J. (1992). Combinations of

genetic algorithms and neural networks: a survey of the state of the art.

In D. Whitely & J. D. Schaffer, International Workshop of Genetic

Algorithms and Neural Networks (pp. 1±37). Los Alamitos, CA:

IEEE Computer Society Press.

Schmitz, G. P. J., & Aldrich, C. (1999). Combinatorial evolution of regression nodes in feedforward neural networks. Neural Networks, 12, 175±

189.

Setiono, R., & Hui, L. C. K. (1995). Use of quasi-Newton method in a

feedforward neural network construction algorithm. IEEE Transactions

on Neural Networks, 6, 273±277.

Tamura, S., & Tateishi, M. (1997). Capabilities of a four-layered feedforward neural network: four layers versus three. IEEE Transactions on

Neural Networks, 8, 251±255.

Whitley, D., Starkweather, T., & Bogart, C. (1990). Genetic algorithms and

neural networks: optimizing connections and connectivity. Parallel

Computing, 14, 347±361.

Yang, J., & Honavar, V. (1998). Experiments with the cascade-correlation

algorithm. Microcomputer Applications, 17, 40±46.

Yao, X., & Liu, Y. (1997). A new evolutionary system for evolving arti®cial neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 8, 694±

701.