Which of these two images most closely matches your own

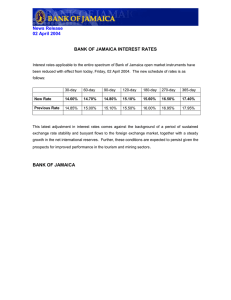

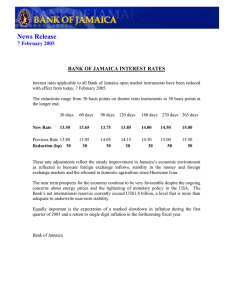

advertisement