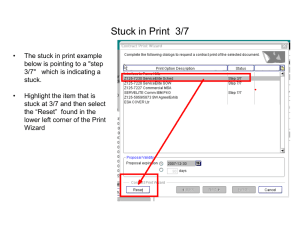

Starting out or getting stuck?

advertisement