Bonus Question 1

Divorce and Dissolution of Civil

Partnerships – bonus question

H and W married six months ago after a brief courtship. From the outset, the relationship

was fraught with problems. W had led a very sheltered life and found some of the sexual

practices H forced her to undergo extremely repugnant. H responded by claiming that W

was very cool towards him, unaffectionate and sexually inhibited. W began to shop frequently, often spending enormous amounts of money on luxury items, despite the fact

that she and H were not well off. Whilst out shopping last week, W saw H emerging from

a restaurant with his arm around X, his secretary. H had been working late recently, and

W accused him of an adulterous affair with his secretary. H was furious at this, denied

any impropriety and slapped W across the face.

Advise W, who wishes to obtain a divorce.

How to Read this Question

Answers should consider whether W would be able to petition for divorce and if so which

fact she would be most likely to use. The question is fairly open – it just asks you to advise

W and therefore it would be appropriate to make a brief mention of the consequences of

divorce. This must, however, necessarily be brief as there is little information about the

resources and needs of the couple.

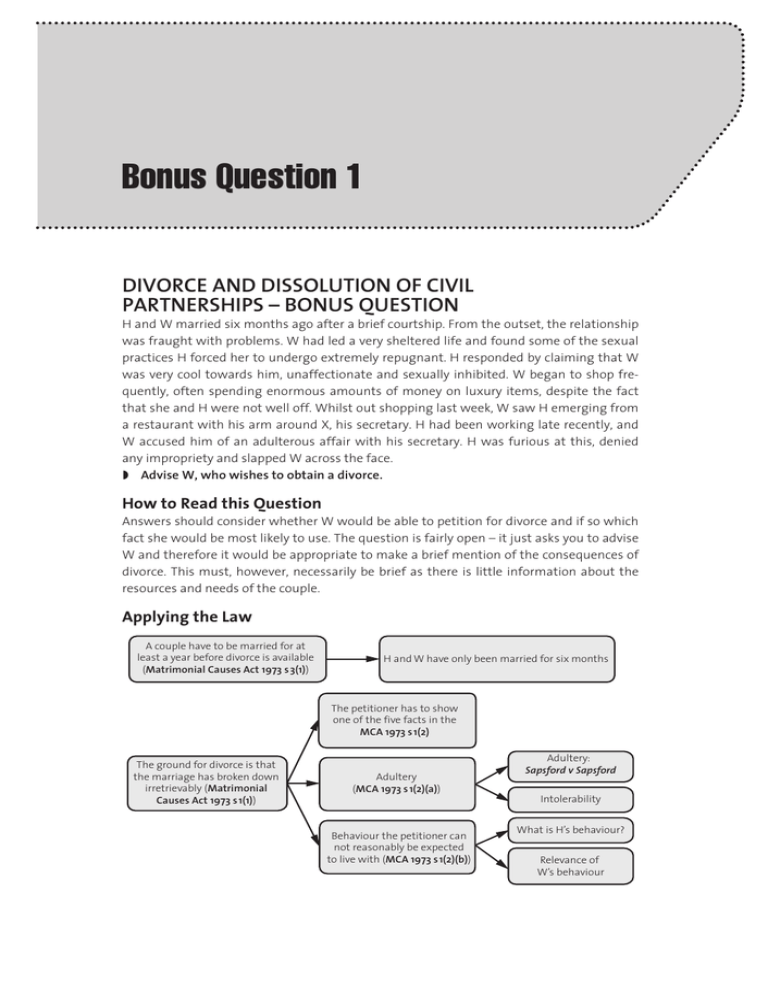

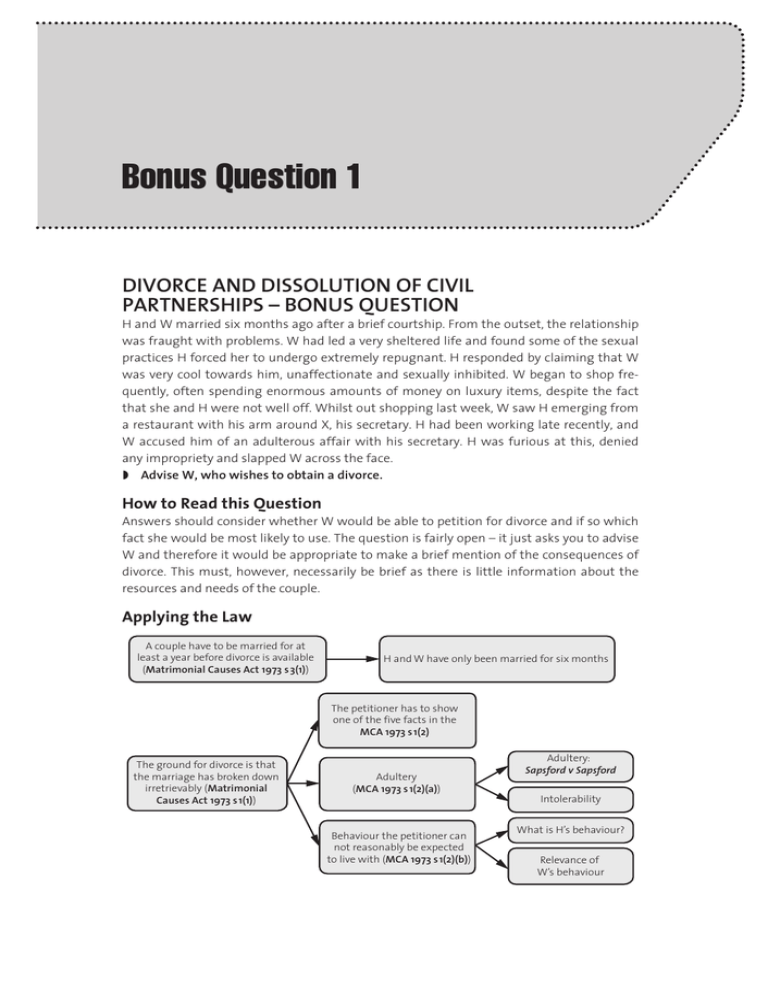

Applying the Law

A couple have to be married for at

least a year before divorce is available

(Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 s 3(1))

H and W have only been married for six months

The petitioner has to show

one of the five facts in the

MCA 1973 s 1(2)

The ground for divorce is that

the marriage has broken down

irretrievably (Matrimonial

Causes Act 1973 s 1(1))

Adultery

(MCA 1973 s 1(2)(a))

Behaviour the petitioner can

not reasonably be expected

to live with (MCA 1973 s 1(2)(b))

Adultery:

Sapsford v Sapsford

Intolerability

What is H’s behaviour?

Relevance of

W’s behaviour

2

Q&A Family Law

ANSWER

In order for W to petition for divorce under the present law, the marriage between her

and H must have lasted for at least one year. The Matrimonial Causes Act (MCA) 1973 s 3(1)

imposes an absolute bar on the presenting of petitions for divorce within one year of marriage, regardless of the hardship or injustice to the petitioner, therefore W cannot petition

for divorce until the expiry of one year from the date of the marriage, although incidents

within that period may be relied on to support the petition: MCA 1973 s 3(2).1

After the expiry of one year from the date of the marriage, W can then petition for divorce

on the grounds that the marriage has broken down irretrievably: MCA 1973 s 1(1). This

concept of irretrievable breakdown must be established by proving one of the five facts in

the MCA s 1(2): Richards v Richards (1972). In this case, proof of one of the five facts would

give rise to the presumption that the marriage had broken down irretrievably and it

seems unlikely that the couple could be reconciled.

The first possible fact that W could rely on is that of adultery and intolerability in the MCA

s 1(2)(a). As the petitioner, W would need to establish that H has committed adultery and

that she finds it intolerable to live with him. Adultery may be defined as voluntary sexual

intercourse between persons of the opposite sex, at least one of whom is married to

another. W will need to establish that H had sexual intercourse with his secretary; sexual

behaviour that does not amount to intercourse is insufficient to establish adultery (Sapsford v Sapsford (1954)). H clearly denies that there has been intercourse and therefore W is

faced with the difficulties of proving that intercourse took place. Circumstantial evidence

of inclination and opportunity may be used: Farnham v Farnham (1925). It seems unlikely

that H had the opportunity to indulge in intercourse in the restaurant, even if he did have

the inclination. Likewise, the recent excuse of working late is very flimsy evidence, since W

does not even know whether the secretary was present or not. Adultery is a serious accusation to make, and the courts have always insisted on strong evidence to support such a

weighty accusation: Serio v Serio (1983). W may therefore experience difficulty in establishing that H had voluntary intercourse with his secretary. If intercourse can be established, W must then show that she finds it intolerable to live with H. The test is subjective

and the intolerability does not have to be caused by the adultery: Cleary v Cleary (1974).

Thus W could rely on H’s sexual practices and his response to her accusation as supporting her claim of intolerability.

The facts do not disclose whether W has ceased to live with H, or whether they are still

living together. Periods of cohabitation that total six months or less may be ignored when

a petition is presented on the basis of adultery: MCA 1973 s 2(1). However, if W continues

to live with H for a period in excess of six months from the last act of adultery complained

of, the petition will fail.

1 In a divorce question remember to check whether the couple can actually divorce. Here, they have only

been married six months so would have to wait. Even though divorce is not immediately available, the

facts that could be relied on after the year should still be discussed.

Bonus Question 1

3

Another option open to W is to petition relying on the fact in s 1(2)(b) that the respondent

has behaved in such a way that the petitioner cannot reasonably be expected to live with

him. In this case, H has insisted on sexual practices that W finds embarrassing and

degrading. There is no detailed evidence as to what these practices are, and there seems

to be a conflict in evidence between W who objects to the practices and H who feels that

W is sexually inhibited, given her sheltered upbringing. Behaviour must be some action or

conduct by one spouse that affects the other and is referable to the marriage (Katz v Katz

(1972)), and it may be that if H’s actions are really perverted, then this will constitute

behaviour such that W cannot reasonably be expected to live with him. However, W could

also argue that H’s lack of understanding, his taunts and his forcing her to do something

she finds repugnant constitute behaviour.2

It would also be possible for W to include in her petition the violent response of H, but H

would probably argue that this was a one-off incident after extreme provocation, and so

should be excluded. H’s relationship with his secretary, if not adulterous, could also be

used by W to support her petition if it was more than merely platonic, or if H were flaunting this friendship to try to force W to be more sexually accommodating, since such relationships can be very destructive: Wachtel v Wachtel (1973). Cumulative incidents can be

included in a petition even if each individual incident would be insufficient, since their

total effect can be examined: Livingstone-Stallard v Livingstone-Stallard (1974). It would

then be necessary to look at the character of the petitioner and respondent (Ash v Ash

(1972)), and ask if it would be reasonable to expect these individuals to live together. This

approach combines a subjective and objective approach: Livingstone-Stallard v Livingstone-Stallard (1974). Whether it is reasonable to expect W to live with H, given their

totally different characters and attitudes to sex, is arguable. Cohabitation is not a bar to

petitions based on behaviour (MCA s 2(3)), but it is important for W to remember that the

longer she lives with H, the weaker her argument that it is unreasonable for her to have

to do so becomes. It is highly likely that H would defend a petition based on behaviour,

and W should be advised of the possibility that H will cross-petition based on her

behaviour. H may well cite her unaffectionate nature, but since this is a state of affairs

rather than deliberate behaviour (Pheasant v Pheasant (1972)), he will need more to

support his petition. A complete and deliberate refusal to have any kind of sexual intercourse might well be behaviour, but her unsatisfactory sexual performance would not be

(Dowden v Dowden (1977)). In addition, H might want to cite W’s financial irresponsibility

in spending large sums of money on luxury items which the family finances could not

afford. Such behaviour might well, if very extreme, result in it being unreasonable to

expect H to live with W (Carter-Fea v Carter-Fea (1987)), especially if H was financially

prudent, yet faced debt and financial ruin because of W’s habit.3

2 The question under s 1(2)(b) is whether this particular petitioner can reasonably be expected to live with

the behaviour of the respondent, It is therefore important to examine the petitioner’s own behaviour as a

less than innocent petitioner might be expected to put up with a less than innocent spouse.

3 Note how the answer considers the effect of continued cohabitation on a petition using the adultery fact

and a petition using the behaviour fact.