Ecological sustainability, social inclusion and the quality of life

advertisement

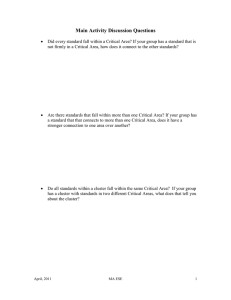

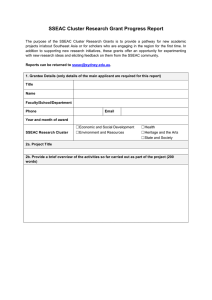

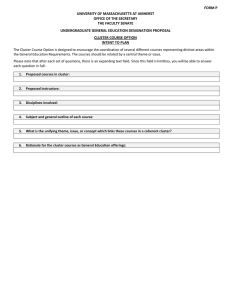

Ecological sustainability, social inclusion and the quality of life: Identifying potentials for prosperity without growth Martin Fritz (GESIS Cologne; Martin.Fritz@gesis.org) and Max Koch (Lund University; max.koch@soch.lu.se) First draft Abstract Recent contributions to ecological economics and related social sciences indicate that issues such as climate change, resource depletion and environmental degradation cannot be effectively addressed under conditions of continued economic growth. This paper aims to identify potentials for prosperity in the absence of economic growth. Its theoretical focus builds on the growing literature that interprets economic policy goals in terms other than quantitative GDP growth and instead highlights individual and social welfare, well-being, capabilities and the quality of life. The paper employs an empirical three-dimensional approach to operationalise ‘prosperity’ in terms of social inclusion, ecological sustainability and the quality of life. Subsequently, it provides and interprets cluster and correspondence analyses for 35 advanced capitalist countries on the basis of data from sources such as the World Bank, EUROSTAT, the Global Footprint Network and the OECD. The result is a typology of ‘prosperity regimes’ that are contrasted with established welfare and employment regime that do not consider ecological indicators. The paper concludes with identifying countries that combine decent levels of prosperity with comparatively low levels of GDP per capita and with raising issues for future research and policy making. 1 Introduction Recent contributions to ecological economics and related social sciences indicate that issues such as climate change, resource depletion and environmental degradation cannot be effectively addressed under conditions of continued economic growth (Victor 2008; Stiglitz et al. 2009; Gough 2011; Royal Society 2012). Indeed, in the absence of evidence for absolute decoupling of GDP growth and carbon emissions, it is remarkable that most economic policy approaches do not question the priority placed on GDP growth. This paper aims to identify potentials for prosperity, which we operationalize in terms of ecological sustainability, social inclusion and the quality of life, in the absence of economic growth. Its theoretical focus builds on the growing literature that interprets economic policy goals in terms other than GDP growth and instead highlights individual and social welfare (Kasser 2009; Koch 2013), wellbeing (Sustainable Development Commission 2007), the quality of life (Nussbaum and Sen 1993) or prosperity (Jackson 2009). However, any transition towards an economy, where GDP growth is de-prioritized and/or replaced by other parameters, will have to take into account and depart from the institutional structures of existing economies and societies. Such transition is facilitated if the different degrees of success to which present countries are promoting prosperity are empirically identified. For this purpose, the paper employs an empirical three-dimensional approach to measure prosperity in terms of social inclusion, ecological sustainability and the quality of life. Subsequently, we carry out cluster and correspondence analyses for 35 advanced capitalist countries using data from different organizations such as the World Bank, EUROSTAT, the Global Footprint Network, and the OECD. On this empirical basis, we create a typology of prosperity regimes that we contrast with established welfare regime typologies (Esping-Andersen 1990) that do not consider ecological indicators. Hence, we aim to identify countries that combine decent levels of prosperity with comparatively low levels of GDP per capita: If overdeveloped countries in terms of GDP have sustained high levels of social welfare but at the cost of severe ecological damage, we ask whether there are also countries with relatively high levels of social cohesion and life quality in combination with comparatively low levels of ecological stress. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implications of the empirical results for policy-making. 2 Theorising prosperity and economic development Prosperity is commonly conceptualised in socio-economic terms, that is, in terms of equity, highlighting distributive issues within growing economies in terms of GDP. While GDP, income growth and rising material standards of living are normally not questioned as priorities in both welfare theories and policy making, there is growing evidence that Western welfare standards are not generalizable to the rest of the planet if environmental concerns such as resource depletion or climate change are considered. Consequently, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2013) emphasizes socio-economic aspects of climate change, including issues of livelihoods and poverty, in its most recent report. Tim Jackson (2009: 488) demonstrates that in order to achieve conditions where the entire world population enjoys an equivalent income to EU citizens today, the global economy would need to improve in absolute decoupling of carbon emissions and economic activity by 11.2 percent per year to 2050 and global carbon intensity would need to be less than one percent of its current level. He concludes that there is as yet ‘no credible, socially just, ecologically sustainable scenario of continually growing incomes for a world of nine billion people.’ (Jackson 2009: 86) Increasing doubts in the capability of GDP as an appropriate measurement of societal development and the associated need to complement it with other types of management (Stiglitz et al. 2009) do normally not lead scholars to question economic growth as an essential requirement for human prosperity as such. This is remarkable, since economics has not always been interpreted as synonymous with a science of prices and the growth of monetary value (De Gleria 1999: 84). In the Physiocratic system, for example, the notion of natural resources was central. The wealth of nations was derived solely from the value of land and the entire economic process was understood by focusing upon a single physical factor: the productivity of agriculture, which was the only kind of work that created value and surplus. In the seventeenth century, William Petty characterised labour as the ‘father’ of material wealth and the ‘earth its mother’ (cited in Marx 1961: 43). This was also reflected in the classical tradition of Adam Smith and David Ricardo as well as by Karl Marx, who, far from abstracting from natural resources and matter in his analysis, began Capital with an examination of the commodity and its twofold character as use value and exchange value, which renders his analysis amenable to ecological laws. While the exchange value aspect of the commodity emphasises the logic of unlimited valorisation, quantitative and geographic expansion of the scale of production and the circular and reversible moments of the production process, the use value aspect 3 considers qualitative matter and energy transformations and hence irreversibility, the narrowed stock of natural resources, and their limited capability to serve as both sources and sinks for the increasing flow and throughput of matter and energy (Koch 2012: 25–35). John Stuart Mill is credited for arguing that economic growth was necessary only up to the point where everyone enjoyed a reasonable standard of living (Victor, 2008: 124; Daly and Farley 2009: 55). He envisioned a ‘stationary state’ of the economy that would move beyond individual status competition and in which both population and the capital stock ceased to grow. Indeed, writing in the 1840s, Mill precluded the essentials of the contemporary ‘degrowth’ debate by not conflating a stationary condition of capital and population with a stationary state of societal development (Mill 1848). John Maynard Keynes (1963: 96), for his part, predicted that by his grandchildren’s lifetime the economy would not need to grow further in order to meet basic human needs. Hence, despite significant disagreement in other matters, these economists have in common not to regard quantitative economic growth as an ahistorical and quasi eternal goal of economic action and policy but as a temporary and historically specific necessity in order to reach a socio-economic level of development, in which basic needs are satisfied and where social actors devote more time to other than economic purposes. Herman Daly’s steady-state economy (SSE) is probably the most prominent contemporary approach in ecological economics. Instead of GDP growth, which is a value index of the physical flows in an economy, the point of departure of a SSE, a primarily physical concept, is that of a relatively stable population and ‘artifacts’ (stock of physical wealth) and the lowest feasible rates of matter and energy throughput in production and consumption. The scale of the economy does not erode the environmental carrying capacity over time. Daly is not in favor of abandoning growth in all sectors of the economy but of viewing it as a ‘process to be consciously and politically monitored and regulated’ (Barry 2012: 133). Hence, while two basic physical magnitudes, population and artifacts, are to be held relatively constant in an SSE, mainly qualitative parameters such as ‘culture, genetic inheritance, knowledge, goodness, ethical codes … the embodied technology, the design, and the product mix of the aggregate total stock of artifacts’ (Daly 1977: 6–7) are free and welcome to evolve. This is also reflected in Daly’s distinction between ‘growth’ and ‘development’, whereby the former refers to a quantitative increase of GDP, and the latter to qualitative change. Continued technological advances in combination with shorter working hours facilitate the maintenance of high 4 living standards with relative low resource consumption and carbon emissions (Koch and Fritz 2013). The goal of an SSE is also supported by ‘degrowth’ economists such as Victor (2008), who has made the greatest effort to date in simulating how an advanced economy and society could cope without economic growth, Martínez-Alier (Martínez-Alier et al. 2010), Kallis (2011) and Sekulova (Sekulova et al. 2013). The case for a SSE and/or ‘degrowth’ is backed up by other disciplines as different as happiness research, sociology of consumption, psychology of well-being and more general concepts of the living standard. Happiness research indicates that once countries have sufficient wealth to meet the basic needs of their citizens and reach a certain per capita income reported levels of (un)happiness show little correlation with GDP growth (Layard 2011). As a corollary, extra happiness provided by extra income is greatest for the poorest and declines steadily as people get richer. Wilkinson and Pickett (2010: 6) make a similar argument in relation to life expectancy. Among the rich countries, life expectancy increases by between two and three years every decade, yet this occurs largely ‘regardless of economic growth, so that a country as rich as the United States no longer does better than Greece or New Zealand …”. Since Thorstein Veblen’s pioneer studies (Veblen 1970) sociologists of consumption argue that in rich countries buying things is not in the first place about the goods themselves but rather about the symbolic message that the act of purchase conveys (Soper et al. 2009). Both acquisition and possession of use values symbolise much of our social standing in society as well as our identity and sense of belonging. What Hirsch (1976) called the competition for ‘positional goods’ is mediated through a genuinely social logic that Bourdieu (1984) referred to as ‘distinction’. This sets in motion a never-ending cycle of defining taste by the avant-garde and keeping-up strategies by the mainstream that plays into the hands of the valorisation interests of various culture industries, but does not contribute to human welfare in the longer term and contradicts the principal reproductive needs of the earth as an ecological system.1 Psychologists of well-being assume that humans must have certain psychological needs satisfied in order to flourish and experience personal wellbeing (Kasser 2009: 175). Notwithstand1 Buying and consuming stuff tends to imbalance the carbon cycle, since such practices are normally bound to matter and energy transformations that necessitate the burning of fossil fuels. 5 ing societal particulars and contexts, these needs include feeling safe and secure but also competent and efficient. People also require love and intimacy but struggle under conditions of loneliness, rejection, and exclusion. Finally, people have a need for autonomy, that is, the ability to choose in relative independence from coercion and internal or external pressures. However, where ‘economic growth is a key goal of a nation’ (Kasser 2011: 194–196), with its encouragement of self-enhancing, hierarchical, extrinsic and materialistic values, the fundamental needs required for human wellbeing are contradicted, since materialistic people are more likely to be dissatisfied with life, to lack vitality, and to suffer from anxiety, depression and addiction problems. Finally, critical economists and philosophers question the utilitarian perspective that individuals are best able to determine what contributes to their quality of life. The capability approach, especially, is not so much concerned with the actual choices that people make as with the options they are free to choose from. While, roughly speaking, ‘functionings’ come close to what psychologists of well-being describe as human needs, ‘capabilities’ include both states of being and opportunities for doing (Hick, 2012). According to Amartya Sen (1993: 37), they encompass ‘such elementary ones as escaping morbidity and mortality, being adequately nourished, having mobility, etc., to complex ones such as being happy, achieving self-respect, taking part in the life of the community, appearing in public without shame’. Martha Nussbaum (2006: 74–8), for her part, proposes a list of ten central human capabilities sought for each and every person, ranging from physical health and integrity to the control of one’s environment. Many of these needs or capabilities are interrelated and complementary and some of them are limited and finite. Most of Nussbaum’s list of central human capabilities requires few, if any, material resources, allowing for a surplus in welfare for one person or one generation while still leaving room for the development of others. Though these theoretical proposals essentially point in the same direction as degrowth economists, insofar they fundamentally question the priority of GDP growth in economic and social policy making, they are as yet mainly studied in ‘separate silos’ (Gough 2011). While much theoretical work remains to integrate these diverse approaches to a coherent theory, the present paper addresses some more practical issues in the transition towards a SSE or at least an economy, where GDP growth is de-prioritised. Our point of departure is that any such transition will have to take into account and depart from the institutional structures of existing economies and societies. Since knowledge on the degrees to which existing societies promote ‘prosperity without growth’ may facilitate institutional learning processes, we aim to empiri6 cally identify present ‘regimes of prosperity’. For this purpose, we operationalise ‘prosperity’ in terms of three dimensions: social inclusion, ecological sustainability and quality of life. We also measure the degree to which these dimensions correspond with the level of the economic development of a country. We measure the economic development of a country in terms of GDP and unemployment. GDP includes all goods and services that are annually produced in a country.2 We make two adjustments to improve the comparability of material living standards across countries: First, we use GDP per capita to account for different population sizes; second, to adjust for currency exchanges rates, we use GDP per capita as purchasing power parity calculations (PPP), calculated by the World Bank for 2010. We also use the average GDP per capita growth of the period 2005-2010, which is likewise provided by the World Bank. Another dimension of economic development – and an explicit goal of European economic governance – is the avoidance of (mass) unemployment. Gainful employment not only ensures the subsistence of people it is also an important source of recognition and social integration (Fritz 2013). By using World Bank data from 2010, we explore how unemployment is related to the three dimensions of prosperity. Following the theoretical discussion above, we operationalise ‘prosperity’ as ecological sustainability, social inclusion and quality of life. Similar approaches include efforts to measure social progress or happiness combining different indicators and dimensions in order to build an index which provides useful information about the levels of ‘prosperity’ for each indicator and as a total score for each country (Porter et al, 2013; Abdallah et al 2012). In contrast, we particularly stress the interdependencies between indicators from different dimensions, thus focussing more on relations rather than on absolute scores. Ecological sustainability is a complex issue including climate change, resource depletion, biodiversity, environmental degradation through air and water pollution, and deforestation (Lafferty and Hovden 2013). We focus on two main indicators that cover crucial aspects of ecology: First, we include CO2 emissions per capita in our analyses by using World Bank data for 2010. Since most production and consumption activities cause CO2 emissions, we expect that, all other things being equal, countries with an advanced degree of economic development and a correspondingly high ma2 As a corollary, various informal economic activities but also a range of unpaid care services provided by family members are excluded. 7 terial living standard emit more CO2 per capita than less developed economies. Conversely, we regard a country, which provides a comparatively high living standard with comparatively low CO2 emissions, as a relatively sustainable country.3 Second, we use the ‘Ecological Footprint’ of a country as an additional indicator for its ecological performance in 2008 (WWF, 2012; Borucke et al., 2013). Social inclusion, the second dimension of prosperity, is operationalised in terms of cohesion and civic participation. ‘Cohesion’ is measured by two components, the distribution of incomes and crime rates. We understand a society, where incomes are distributed relatively equally and crime rates are low, to be relatively cohesive. As indicator for income (in)equality we use the Gini Index.4 Crime rates are measured at the example of homicide rates.5 ‘Civic participation’ is also measured by two components. First, we consider the ‘actual’ participation at the example of voter turnout in the last national election by using OECD data for the period 2008-2012. Second, we include an indicator that estimates the impact of the general public on state regulations and government action (‘consultation’) by using OECD data from 2008. The third dimension of prosperity is the quality of life. Many scholars distinguish between objective and subjective factors in the assessment of the quality of life. Both factors are doubtless relevant: objective living conditions are constantly seen as in need of improvement, since individual satisfaction with these conditions is relative and often the result of psychological adaption processes. Subjective satisfaction is likewise important, since increases in material living standards can be accompanied by growing subjective dissatisfaction, especially in unequal societies characterised by advanced status competition (Kasser, 2011). In the following analysis, we measure both objective and subjective factors. As an indicator for the objective quality of life we use ‘life expectancy’ as provided by the OECD for the period 2009- 3 This does not mean that countries with relative low carbon emissions and Ecological Footprint are necessarily ‘sustainable’ in the absolute sense as defined by the WWF (2006: 19). According to this definition, only a ‘footprint lower than 1.8 global hectares per person, the average biocapacity available per person on the planet’, denotes sustainability at global level. 4 Different organisations provide data on the GINI, including the OECD, EUROSTAT and the World Bank. 5 For this indicator, we use OECD data for the period 2008-2011. 8 2012, and for the subjectively perceived quality of life we consider ‘subjective health’ and ‘general life satisfaction’, both measured using OECD data from the period 2006-2012. Data analyses We collected data for 35 countries, most of which are member states of the EU and the OECD: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, and the USA. Clustering countries to regimes As a first step, we carried out cluster analyses to test whether countries can be grouped into ‘prosperity regimes’ in terms of three dimensions: social inclusion, sustainability and quality of life plus economic development.6 A hierarchical cluster analysis, using the Ward criterion and squared Euclidean distances, led to a solution of three clusters. We then tested the stability of this solution by running several other cluster analyses with different criteria (single linkage, average linkage etc.). Finally, we ran a k-means cluster analysis as optimisation method using the cluster means of the first Ward cluster analysis as starting points. Since cross validation of these two cluster analyses shows little divergence (Table 1), we use the results of this last k-means cluster analysis as the basis for our interpretation. Table 1: Cross-validation of clustering countries K-means Method Ward Method Total 6 Total Cluster 1 Cluster 2 Cluster 3 Cluster 1 13 0 1 14 Cluster 2 0 6 0 6 Cluster 3 1 3 10 14 14 9 11 34 Luxembourg was omitted from the cluster analyses; due to its extreme values on many indicators it statistically doesn’t fit into any cluster. 9 The five countries that changed their cluster according to Table 1 were Germany and New Zealand, which interchanged their positions, and three countries from Eastern Europe, which shifted from cluster 3 to cluster 2: Hungary, Poland and the Slovak Republic. Overall, the 34 countries were distributed across the three following clusters: Cluster 1: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and the USA. Cluster 2: Brazil, Chile, Estonia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Slovak Republic, and Turkey. Cluster 3: Czech Republic, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain. 10 Table 2: Mean values of the three clusters Indicator Cluster 1 2 3 CO2 10,44 6,69 7,82 GDP 41627,58 18342,77 29489,78 GINI 29,34 39,28 31,35 UNEMPLOYMENT 7,24 10,23 8,85 CONSULTATION 8,24 5,73 6,95 74,57 67,44 69,36 SATISFACTION 7,28 5,92 6,14 HOMICIDE 1,39 7,89 1,26 FOOTPRINT 6,04 3,70 4,61 HEALTH 77,00 58,11 62,55 LIFEEXPECTANCY 80,98 74,97 81,25 0,69 2,92 1,05 VOTERS GROWTH Figure 1: Differences between prosperity clusters (z-scores) 1,5 1 0,5 0 -0,5 -1 -1,5 11 Cluster 1 Cluster 2 Cluster 3 Table 2 (in numbers) and Figure 1 (graphically) contain information about the characteristics of the three clusters in terms of their mean values for the indicators analysed. The first cluster assembles the richest countries in terms of GDP per capita. At the same time, these are characterised by the highest values of general life satisfaction and the lowest degrees of income inequality and unemployment. While economic development is to some extent complemented by social equity, this group of countries features the highest CO2 emissions and Ecological Footprints among the three clusters. In other words, countries such as USA, Germany, Sweden or Belgium are united by the coincidence of a high level of economic development, social standards and perceived life satisfaction. Yet this comes at the price of an extremely unsustainable ecological performance. The second cluster marks the opposite end of the spectrum. The countries assembled here perform relatively well in terms of sustainability but much worse in all other respects. Economic development continues to be at the comparatively lowest level despite the highest growth rates in the ‘emerging markets’ of Brazil, Russia or Mexico. However, this growth is not accompanied by full employment, since this group of countries suffers from the comparatively highest unemployment rates. Social inclusion and quality of life indicators are far below the first group of countries with examples including a six years shorter life expectancy and six times higher homicide rates. While these countries fail to achieve socio-economic minimum standards that can be regarded as absolutely necessary for prosperity, CO2 emissions and Ecological Footprints are the lowest among the clusters and countries analysed. While the first two clusters indicate the difficulties of combining a decent socio-economic and material living standard with ecological sustainability, the third cluster provides some evidence that production and consumption practices that spare the environment to a certain extent can be reconciled with comparatively high material living standards and principles of social equity. This cluster brings together Mediterranean countries such as France7, Italy, Greece and Spain, East European countries such as the Czech Republic and Slovenia, East Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea as well as New Zealand. This rather diverse mix of countries is united by medium-level degrees of economic development. Yet, the ecological stress caused by this development is significantly lower than in the economically lead7 The environmental performance of France is co-determined by its massive use of nuclear energy. 12 ing countries and only slightly higher than in the second group of ‘emerging markets’. Of special interest is the consideration of the social inclusion and quality of life indicators. Whereas income inequality is only marginally higher than in the first cluster, homicide rates are somewhat lower. Also life expectancy is slightly higher in the third cluster than in the first. Whereas these ‘objectively’ measurable indicators confirm earlier studies (Wilkinson and Pickett 2010)8, we arrive at a somewhat different picture when also considering ‘subjectively’ perceived indicators for political participation and the quality of life. Here, the first cluster scores significantly higher, featuring higher voter turnout and more possibilities for the general public to influence governmental decisions (‘consultation’). Especially striking are the differences with respect to subjective health and life satisfaction, where the third cluster is close to the second and the economically most developed countries have a solid lead. Hence, not objective distances but individually perceived differences in political participation and life quality characterise the division between the economically leading but ecologically most harmful countries and the economically fairly well developed countries that display greater social inclusion and objective quality of life scores as well as greater sustainability. It is a theoretical and empirical challenge to explain the difference between objectively measured and subjectively perceived indicators of prosperity in the third cluster of countries. Theoretically, we would have expected a greater degree of accordance, since previous studies suggested that more egalitarian countries tend to also display higher ‘happiness’ scores (Layard 2011; Wilkinson and Pickett 2010), for example. One could hypothesise that the ‘economic success’ and the general way of life in the countries of the first cluster functions as the benchmark for citizens of countries in the second and third cluster who then are less satisfied with their lower standard of living and thus somewhat underestimate the socio-ecological performances in their own countries9. There might also be a link between the degree of activity and perceived political influence of citizens and their general life satisfaction. 8 This study indicates that countries such as Cuba, Costa Rica or Greece achieve the same life expectancy as the USA, Germany or the UK – with considerably less GDP growth and resource depletion. 9 Similar to what Bourdieu (1984) has described for social classes, the cycle of keeping up with the avant-garde may also occur at country level: Here, the advanced Western countries of cluster 1 serve as the upper-class, cluster 2 as the underclass and cluster 3 would be the middle-class. 13 One way to empirically shed light on these issues is to investigate how strong the effect of the various single indicators are for the generation of the three clusters, and how all indicators relate to each other. Table 3 displays the impact of the indicators for the separation of clusters. GDP has the highest F-value and thus separates the cluster the most. Other indicators with strong effects are life expectancy, the Ecological Footprint and life satisfaction. Yet the fact that the effect of GDP is by far the strongest indicates the amount of the challenge any political approach will face when attempting to deprioritise GDP growth and complement/replace it with social and ecological parameters. Table 3: F-values of indicators from ANOVA statistics of the k-means cluster analysis Indicator F-value CO2 3,758 GDP 69,998 GINI 7,179 UNEMPLOYMENT 1,913 CONSULTATION 2,599 VOTERS 1,217 SATISFACTION 17,327 HOMICIDE 7,082 FOOTPRINT 22,202 HEALTH 7,316 LIFEEXPECTANCY 48,834 GROWTH 10,905 Relationships between indicators In a second step, we apply correspondence analysis to empirically explore the relations between the three prosperity dimensions and the economic performance of the 35 countries. This method allows for visually depicting the latent structures and correlations of all interdependent variables within maps (Bourdieu, 1984; Blasius and Greenacre, 2006; Greenacre, 2007). To give every indicator and every country the same weight the macro data is standardized through the use of the two-step procedure of ranking and doubling (Greenacre, 2007; Blasius and Graeff, 2009). In total, we compiled and analyzed data for twelve indicators in or near 2010, which we collected from EUROSTAT, the World Bank, the OECD and the Global Footprint Network. We interpret the resulting maps as follows (Blasius and Graeff, 2009): 14 • The greater the distance of a variable or country from the centroid, which depicts the overall average of all 35 countries, the stronger is its contribution to the respective axis within the two-dimensional map. If, for example, the indicator GDP is on the first dimension furthest from the centroid, this dimension is mostly determined by differences in the level of economic development between the countries; • The correlation between two indicators is expressed by the angle of their trajectories in the map, whereby a 90° angle reflects complete independence, that is, the absence of a correlation between variables (0° represents a perfect positive correlation and 180° a perfect negative); • The doubling and ranking procedure results in two endpoints for each variable/indicator, a positive and a negative one (indicated as _hi and _lo), which are both depicted in the maps and which are perfectly mirrored by the centroid, or in other words: they are negatively correlated; the angle of their trajectory is 180°, a straight line passing the centroid. We inserted these lines for all indicators, so that bundles of indicators emerge. Together, the two dimensions of the map explain 51.5 per cent of variation in the data (Figure 2). The indicators with the highest loads on their respective dimensions are GDP, Ecological Footprint, satisfaction and life expectancy on the x-axis, and homicide rates and CO2 emissions on the y-axis. Overall, the indicators take the form of two broad bundles. The first one stretches from the upper left to lower right and the other from the upper right to lower left. The dotted lines through these bundles represent the substantial latent dimensions whose meaning is determined by the interdependency of the indicators in the bundles. The first of these latent dimensions stands for the material living standard and general life satisfaction in a broad sense. It captures GDP and unemployment as economic indicators, the GINI coefficient for income inequality, subjective health and life satisfaction as well as the two ecological indicators CO2 emissions and Ecological Footprint. The associations between these indicators largely confirm the results from the cluster analyses. The upper left quadrant of the map is characterised by a concentration of indicators measuring the dimensions ‘material living standard’ and ‘satisfaction’. A relative high level of GDP per capita is associated with relative high values for subjective health, life satisfaction and a relative low value of the GINI coefficient. Further from GDP yet still correlated we find comparatively high Ecological Footprints, low unemployment rates and high voter turnouts. 15 Interestingly, the fact that relatively high CO2 emissions per capita mark the most distant indicator within this bundle suggests that the link between economic development and CO2 emissions is weaker than expected in most ‘degrowth’ approaches. This link could be further loosened through adequate policies, for example public subsidies and support of renewable energy use. Yet an adequate reduction of the Ecological Footprints appears to be a far greater challenge as the lower right quadrant of the eco-social field indicates. Relatively low footprints, especially, and, to a lesser degree, comparatively low CO2 emissions – our indicators for ecological sustainability – are associated with relatively low material living standards and relatively low values of perceived life satisfaction. The second bundle and its latent dimension are constituted by four indicators: homicide rates, economic growth, life expectancy and ‘consultation’ (our indicator to measure the impact of civil society on government decisions). On the basis of previous studies and the above cluster analyses we expected the latter indicator to be closer to ‘voter turnout’, since ‘consultation’ likewise measures the degree of citizens’ socio-political participation. At the same time, the statistical connection of two of our four social inclusion indicators – homicide and consultation – and also life expectancy to the level of economic development is very weak. In contrast, these indicators correlate positively with low growth rates. This suggests that at least some aspects of social inclusion and the quality of life in particular may be reached with slower GDP growth rates and less environmental stress than is the case in countries of the first cluster. 16 Figure 2: Correspondence analysis; map of variables 2010 λ2=0.046 (13.0%) Low inclusion and low quality of life CO2_hi HOMICIDES_hi Environmental stress High material living standard and high satisfaction GROWTH_hi LIFEEXPECTANCY_lo 0.5 FOOTPRINT_hi UNEMPLOYMENT_lo VOTERS_hi CONSULTATION_lo SATISFACTION_hi GINI_lo λ1=0.136 (38.5%) HEALTH_lo GDP_hi 0.5 HEALTH_hi GINI_hi GDP_lo SATISFACTION_lo CONSULTATION_hi UNEMPLOYMENT_hi VOTERS_lo FOOTPRINT_lo LIFEEXPECTANCY_hi GROWTH_lo HOMICIDES_lo CO2_lo High inclusion and high quality of life 17 Low material living standard and low satisfaction In a last step, we plotted the positions of the 35 countries onto the map (Figure 3). In this way, the overall ‘prosperity performance’ of each country becomes identifiable. For example, countries can be located in positions that combine relative high values for ‘inclusion’ and ‘quality of life’ with lower values for ‘material living standard’ and overall ‘satisfaction’. This applies to the cases in the lower left quadrant, particularly to Switzerland, New Zealand, the UK, Italy and Spain. Most economically advanced are the Nordic states, but also countries with a liberal welfare tradition such as the USA, Australia and Canada. These all figure in the upper left quadrant. The higher their position within this quadrant the less socially inclusive these countries, since they move on the second dimension towards the negative spectrum, characterised by relatively weak inclusion and low quality of life. This is exemplified by the respective positions of the USA and Norway. The most prosperous country in respect to all dimensions including sustainability is located at the extreme lower left of the map: Switzerland.10 Figure 3 also displays the positions of the three clusters as the mean scores of their respective countries. As might be expected from the results of the cluster analysis, cluster 1 emerges on the left side of the spectrum, the most economically advanced but unsustainable part of the eco-social field. Cluster 2 is on the opposite side and surrounded by less economically developed and more ecologically sustainable countries. It is also much less associated with social inclusion and quality of life than cluster 1. Cluster 3 takes a middle position regarding the material standard of living and life satisfaction, while it is equally advanced in terms of social inclusion and the quality of life as cluster 1. Hence, in the correspondence analysis, cluster 3 has caught up with cluster 1 on this dimension without simultaneously moving towards the area of environmental stress. 10 According to our cluster analysis, Switzerland is part of the largely unsustainable first cluster. This is mainly due to its huge GDP per capita, which is the most important indicator for separating the clusters (Table 3). 18 Figure 3: Map of countries and prosperity regimes λ2=0.046 (13.0%) Low inclusion and low quality of life LU RU Enivronmental Stress EE US High material living standard and high satisfaction BE CZ 0.5 NL KR FI AU IL social-democratic welfare regime CL CA DE DK AT SK cluster1 NO MX SI IE cluster3 PL conservative welfare regime FR EL UK CH TR 0.5 liberal welfare regime SE BR cluster2 JP HU NZ IT PT ES High inclusion and high quality of life 19 Low material living standard and low satisfaction λ1=0.136 (38.5%) Following Esping-Anderson (1990), we finally included the positions of his three welfare regimes in the map. In contradiction to hopes that ‘social-democratic’ welfare regimes are best placed to build the green dimension of the state (Dryzek in Gough et al., 2008; see Koch and Fritz forthcoming), these countries are positioned in the lower section of the upper left quadrant. Hence, social-democratic countries combine high levels of economic prosperity with social equity but also with high Ecological Footprints and environmental stress. In terms of prosperity regimes these countries are in fact closer to the ‘liberal’ welfare world than one would expect on the basis of Gough et al. (2008). Far from displaying sufficiently low environmental footprints and CO2 emissions the conservative welfare regime family scores best in terms of environmental performance. It is also closest located to high life expectancy and ‘consultation’ as a measurement of the impact the general public is able to make on state regulation and government action. Switzerland might indeed serve as a good example in this regard. Conclusions and challenges for policy-makers Building on the growing academic literature in favour of a de-prioritisation of GDP growth as socio-economic policy goal and of conceptualising prosperity without growth, this paper set out to comparatively identify the potentials of 35 advanced capitalist countries of achieving such prosperity. It operationalised prosperity in terms of three dimensions (ecological sustainability, social inclusion and the quality of life) and empirically analysed these in relation to economic development. First of all, we would like to clarify that no country of our sample meets the absolute sustainability standards identified in the WWF’s Living Planet Report (WWF 2006). Our empirical results largely confirm previous studies that question the feasibility of absolutely decoupling GDP growth from resource intensity and economic stress. However, this applies more to the Ecological Footprint than to carbon emissions, since the latter are less associated with GDP. Policy strategies that support the investment in and the use of renewable energies could assist this trend towards dissociation between economic development and carbon emissions further.11 11 Current ‘market-oriented’ climate policies including the EU Emissions Trading System have opened up additional investment area for financial capital but have contributed next to nothing to climate change abatement. Much evidence points to the conclusion that direct state action and/or climate taxes would be a more effective policy means (Lohman, 2010; Koch, 2012: 155-66). 20 The cluster analyses led to three groups of countries with corresponding prosperity regimes. The first cluster assembled countries with such different welfare traditions and institutional structures as the US, Sweden and Germany. These countries are united by their relative success in economic development and social equity. Yet the fact that this cluster is also the least ecologically sustainable again supports authors who doubt the possibility of absolutely decoupling GDP growth and resource intensity. Indeed, any transformation to global sustainability is significantly undermined by the Western ‘way of life’, and by the fact that it continues to be the role model for the rest of the world. Not accidentally, the second cluster of the ‘emerging markets’ of Brazil, Russia or Mexico reflects the growth model of the industrialised countries of the first clusters in many ways. Similar to earlier development phases of the latter countries, these countries are characterised by quickly developing markets and rapid GDP growth, social disintegration and anomie as well as relatively low carbon emissions and Ecological Footprints. However, to the extent that these countries continue to copy the previous development path of the Atlantic space, their ecological performance is likely to deteriorate (Koch 2012: 122-136). The third cluster brings together countries as diverse as Italy, Slovenia, South Korea and New Zealand and comes closest to provide evidence for the feasibility of policy strategies to simultaneously foster economic development, social cohesion and ecological sustainability. This applies much more for objectively measurable than to subjectively perceived prosperity indicators. A final result of our correspondence analyses is that there are significant prosperity potentials for most countries that do not lie in the further expansion of material standards and needs but in the provision of increased possibilities of political codetermination, especially at local levels, and which might in turn also enhance subjective life satisfaction of the citizens. Future research should empirically and theoretically focus on the difference between objectively measured and subjectively perceived indicators of prosperity, particularly in the countries of our third cluster. From the perspective of institutional learning, a comparative in-depth analysis of these countries’ institutional structures – for example in relation to degrees and kinds of corporatism and environmental regulation (Liefferink et al. 2009) – highlighting commonalities and differences appears likewise promising A significant issue for both research and policy-making that arises from the present paper, which should be explored further, is how subjectively perceived quality of life (well-being) and democratic participation can be achieved and increased under conditions of economically stable and increasingly eco21 logically sustainable economies. Empirically, future studies should include more countries, particularly from non-OECD countries, as well as alternative indicators that more precisely focus on the contrast between objective and subjective indicators of welfare, well-being and the quality of life. References Abdallah S, Michaelson J, Shah S, Stoll L, Marks N (2012) The Happy Planet Index: 2012 Report. A global index of sustainable well-being (nef: London) Barry, J. (2012) ‘Towards a political economy of sustainability’, in M. Pelling, D. Manuel-Navarrete and M. Redclifft (eds) Climate Change and the Crisis of Capitalism, London: Routledge. Blasius, J. and Graeff, P. (2009), ‘Economic freedom, wealth and corruption. Analyzing their empirical connection by means of correspondence analysis’, in P. Graeff and G. Mehlkop (eds.), Capitalism, democracy and the prevention of war and poverty, London: Routledge. Blasius, J. and Greenacre, M. (2006), ‘Multiple correspondence analysis and related methods in practice’, in M. Greenacre and J. Blasius (eds.), Multiple correspondence analysis and related methods. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall. Borucke, M., Moore, D., Cranston, G., Gracey, K., Iha, K., Larson, J., Lazarus, E., Morales, J.C., Wackernagel, M. and Galli, A. (2013), ‘Accounting for demand and supply of the biosphere’s regenerative capacity: The National Footprint Accounts’ underlying methodology and framework’, Ecological Indicators, 24, 518-533. Bourdieu, P. (1984), ‘Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste’, Harvard: Harvard University Press. Daly, H. (1977) Steady State Economics, San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman. Daly, H. and J. Farley (2009) Ecological Economics. Principles and Applications. Washington, DC: Island Press. De Gleria, S. (1999) ‘Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen’s Approach to Economic Value: A Theory Based on Nature with Man as its Core’ in K. Mayumi and J.M. Gowdy (eds) Bioeconomics and Sustainability. Essays in Honor of Georgescu-Roegen, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Cambridge: Polity. Fritz, M. (2013) ‘Non-Standard Employment and Anomie in the EU, in Koch, M. and Fritz, M. (eds) NonStandard Employment in Europe: Paradigms, Prevalence and Policy Responses, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Gough, I. (2011) Climate Change and Public Policy Futures, London: British Academy. Gough, I., Dryzek, J., Gerhards, J., Lengfield, H., Markandya, A. and Ortiz, R. (2008) ‘JESP Symposium: Climate Change and Social Policy’, Journal of European Social Policy 18 (4): 325-344. Greenacre, M. (2007) Correspondence analysis in practice, 2nd edition, Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall. Hick, R. (2012) ‘The Capability Approach: Insights for a New Poverty Focus’, Journal of Social Policy 41 (2): 291–308. Hirsch, F. 1976. The Social Limits to Growth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 22 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2013) Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Summary for Policymakers, available online at http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/uploads/WGI_AR5_SPM_brochure.pdf. Jackson, T. (2009) Prosperity without Growth? Economics for a Future Planet, London: Earthscan. Kallis, G. (2011) ‘In Defence of Degrowth’, Ecological Economics No. 70, 873-80. Kasser, T. (2009) ‘Psychological Need Satisfaction, Personal Wellbeing, and Ecological Sustainability’, Ecopsychology 1 (4): 175–180. Kasser, T. (2011) ‘Capitalism and Autonomy’ in V.I. Chirkov et al. (eds) Human Autonomy in Cross-Cultural Context, New York: Springer. Keynes, J. M. (1963) ‘Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren’ in J .M. Keynes (ed) Essays in Persuasion, New York: W.W. Norton. Koch, M. (2012) Capitalism and Climate Change. Theoretical Analysis, Historical Development and Policy Responses, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Koch, M. (2013) ‘Welfare after Growth: Theoretical Discussion and Policy Implications’, International Journal of Social Quality 3 (1): 4-20. Koch, M. and Fritz, M. (2013) ‘Conclusion: Non-Standard Employment: Concept, Empirical Results and Policy Implications’, in Koch, M. and Fritz, M. (eds) Non-Standard Employment in Europe: Paradigms, Prevalence and Policy Responses, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Koch, M. Fritz, M. (forthcoming) ‘Building the Eco-social State: Do Welfare Regimes Matter? Forthcoming in Journal of Social Policy. Lafferty, W. and Hovden, E. (2003) ‘Environmental policy integration: Towards an analytical framework’, Environmental Politics 12 (3) 1-22. Layard, R. 2011. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science. London: Penguin Books. Liefferink, D., Arts, B., Kamstra, J. and Ooijevaar, J. (2009) ‘Leaders and laggards in environmental policy: A quantitative analysis of domestic policy inputs’, Journal of European Public Policies 16 (5), 677-700. Lohmann, L. (2012) ‘Uncertainty markets and carbon markets: Variations on Polanyian Themes’, New Political Economy 15 (2): 225-54. Martinez-Alier, J., U. Pascual, F.D. Vivien, and E. Zaccai (2010) ‘Sustainable De-growth: Mapping the Context, Criticism and Future Prospects of an Emergent Paradigm’, Ecological Economics 69: 1741–1747. Marx, K. (1961) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 1. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. Mill, J. S. (1848) Principles of Political Economy. Book IV. London: Longmans, Green and Co. Nussbaum, M. C. (2006) Frontiers of Justice. Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. Cambridge: The Belknap Press. Nussbaum. M. and Sen, A. (1993) The Quality of Life, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Porter, M.E, Stern, S, Artavia Loria, R (2013) Social Progress Index 2013, The Social Progress Imperative. Sekulova, F, Kallis, G., Rodriguez-Labajos, B. and Schneider, F. (2013) ‘Degrowth: From Theory to Practice’, Journal of Cleaner Production 38: 1-6. 23 Sen, A. (1993) ‘Capability and Wellbeing’ in M.C. Nussbaum and A. Sen (eds) The Quality of Life, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Soper, K., Ryle, M.H. and Thomas, L. (2009) The Politics and Pleasures of Consuming Differently, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Stiglitz, J., Sen, A. and Fitoussi, J. (2009) ‘Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress’, available online at http://www.stiglitz-senfitoussi.fr/documents/rapport_anglais.pdf. Sustainable Development Commission (2007) ‘Living Well – Within Limits’, SDS Discussion Document on Wellbeing Indicators for Sustainable Development. The Royal Society (2012) ‘People and the Planet’, The Royal Society Science Policy Centre, Report 01/12, London. Veblen, T. (1970) The Theory of the Leisure Class. London: Unwin Books. Victor, P. A. (2008) Managing without Growth: Slower by Design, not Disaster, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Wilkinson, R. and Pickett, K. (2010) The Spirit Level. Why Equality is Better for Everyone. London: Penguin. WWF (2006) Living Planet Report 2006, London and Oakland: Gland. WWF (2012) Living Planet Report 2012, WWF International, Gland, Switzerland. 24