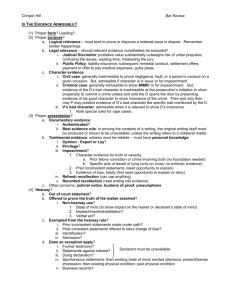

the williamson standard for the exception to the rule against hearsay

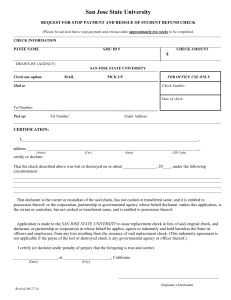

advertisement