VIEWPOINT

Deciphering Harm Measurement

Gareth Parry, PhD

Amelia Cline, BSPH

Don Goldmann, MD

I

MPROVEMENT IN HEALTH CARE QUALITY AND SAFETY CAN

be notable when measurement criteria are clear, evidence is strong, and policy and interventions are focused.

Despite this potential, progress in reducing patient harm

in hospitals has been slow.1 In an effort to catalyze progress, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

is funding a national program, Partnership for Patients (P4P),

with the ambitious goal of reducing “preventable hospitalacquired conditions” by 40% by 2013, focused initially on

9 complications.2 Although the program’s goal formally

includes only preventable harm, the HHS notes “the Partnership will target all forms of harm” and provide guidance

to hospitals for reducing “all-cause harm.” Simultaneously,

the list of “serious reportable events” for which the Centers

for Medicare & Medicaid Services will modify physician and

health care institution payment is increasing. However, delay

in defining a measurement strategy for harm has slowed progress and has created confusion. The need to reach consensus on robust, pragmatic measures for assessing and tracking harm rates has therefore become urgent.

Harm Measures

The terms harm, adverse events, and injuries are often used

interchangeably. The Canadian Disclosure Guidelines3 provide particularly useful definitions: harm is “an outcome that

negatively affects a patient’s health and/or quality of life”;

an adverse event is “an event which results in unintended

harm to the patient, and is related to the care and/or services provided to the patient, rather than to the patient’s underlying medical conditions.”

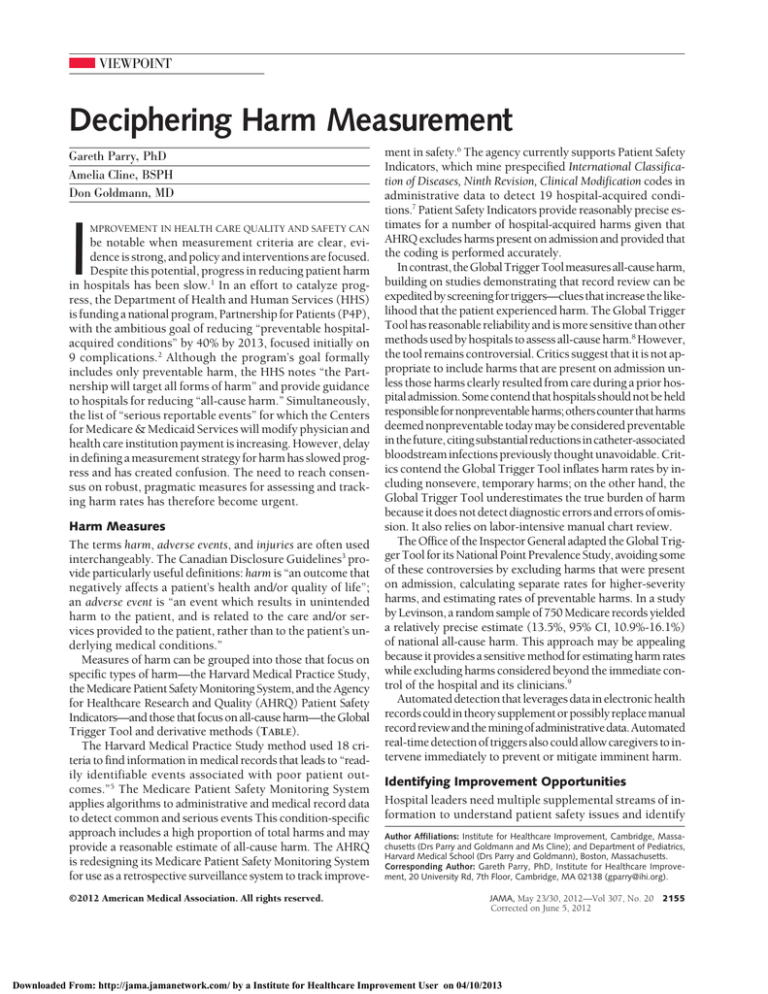

Measures of harm can be grouped into those that focus on

specific types of harm—the Harvard Medical Practice Study,

the Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System, and the Agency

for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Patient Safety

Indicators—and those that focus on all-cause harm—the Global

Trigger Tool and derivative methods (TABLE).

The Harvard Medical Practice Study method used 18 criteria to find information in medical records that leads to “readily identifiable events associated with poor patient outcomes.”5 The Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System

applies algorithms to administrative and medical record data

to detect common and serious events This condition-specific

approach includes a high proportion of total harms and may

provide a reasonable estimate of all-cause harm. The AHRQ

is redesigning its Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System

for use as a retrospective surveillance system to track improve©2012 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

ment in safety.6 The agency currently supports Patient Safety

Indicators, which mine prespecified International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes in

administrative data to detect 19 hospital-acquired conditions.7 Patient Safety Indicators provide reasonably precise estimates for a number of hospital-acquired harms given that

AHRQ excludes harms present on admission and provided that

the coding is performed accurately.

In contrast, the Global Trigger Tool measures all-cause harm,

building on studies demonstrating that record review can be

expedited by screening for triggers—clues that increase the likelihood that the patient experienced harm. The Global Trigger

Tool has reasonable reliability and is more sensitive than other

methods used by hospitals to assess all-cause harm.8 However,

the tool remains controversial. Critics suggest that it is not appropriate to include harms that are present on admission unless those harms clearly resulted from care during a prior hospital admission. Some contend that hospitals should not be held

responsiblefornonpreventableharms;otherscounterthatharms

deemed nonpreventable today may be considered preventable

in the future, citing substantial reductions in catheter-associated

bloodstream infections previously thought unavoidable. Critics contend the Global Trigger Tool inflates harm rates by including nonsevere, temporary harms; on the other hand, the

Global Trigger Tool underestimates the true burden of harm

because it does not detect diagnostic errors and errors of omission. It also relies on labor-intensive manual chart review.

The Office of the Inspector General adapted the Global Trigger Tool for its National Point Prevalence Study, avoiding some

of these controversies by excluding harms that were present

on admission, calculating separate rates for higher-severity

harms, and estimating rates of preventable harms. In a study

by Levinson, a random sample of 750 Medicare records yielded

a relatively precise estimate (13.5%, 95% CI, 10.9%-16.1%)

of national all-cause harm. This approach may be appealing

because it provides a sensitive method for estimating harm rates

while excluding harms considered beyond the immediate control of the hospital and its clinicians.9

Automated detection that leverages data in electronic health

records could in theory supplement or possibly replace manual

record review and the mining of administrative data. Automated

real-time detection of triggers also could allow caregivers to intervene immediately to prevent or mitigate imminent harm.

Identifying Improvement Opportunities

Hospital leaders need multiple supplemental streams of information to understand patient safety issues and identify

Author Affiliations: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Cambridge, Massachusetts (Drs Parry and Goldmann and Ms Cline); and Department of Pediatrics,

Harvard Medical School (Drs Parry and Goldmann), Boston, Massachusetts.

Corresponding Author: Gareth Parry, PhD, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 20 University Rd, 7th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02138 (gparry@ihi.org).

JAMA, May 23/30, 2012—Vol 307, No. 20

Corrected on June 5, 2012

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Institute for Healthcare Improvement User on 04/10/2013

2155

VIEWPOINT

Table. Summary of Approaches Used to Measure Patient Harm in the United States

Outcome Measure

Method Summary

Features

Medicare

Department of

patient

Health and

safety

Human

monitoring

Services

system

Patient

Safety Task

Force, CMS

Method

Creator

Specified unintended harms,

injuries, or loss that is

more likely associated

with a patient’s

interaction with the health

care delivery system than

from an attendant

disease process

Full medical records are sent to 2 clinical data

abstraction centers and are screened by

trained abstractors for specific types of adverse

events using an electronic data collection

software program (MedQuest)

Administrative data are then used to identify specific

postdischarge events; eg, readmissions and

30-d postoperative mortality

Focuses on events that are likely to be

documented and discoverable in the

medical record, likely associated

with a specific process of care,

commonly responsible for serious

morbidity or mortality, preventable or

repairable; no assessment of

preventability or severity

PSIs

AHRQ

Adverse events: resulting

from exposure to the

health care system, likely

amenable to prevention

by changes to the system

Review by mining administrative data

Each of the 19 PSIs include a set of ICD-9-CM

codes specified by AHRQ, and these codes are

mined from a hospital’s administrative data

Rates of each PSI are calculated using

AHRQ-defined denominators

PSIs are harm-specific and do not

comprise an aggregate measure of

all-cause harm preventability not

formally assessed

June 2009 adoption of

present-on-admission codes

improved specificity

Global

Trigger

Tool

Institute for

Healthcare

Improvement

Adverse events: unintended

physical injury resulting

from or contributed to by

medical care that requires

additional monitoring,

treatment, or

hospitalization or that

results in death

2-Stage manual medical record review

Primary stage: 2 trained clinical providers (eg,

nurse, clinical pharmacist) independently review

records for 53 specific triggers and any

resultant adverse events

Disagreements are resolved by consensus

Secondary stage: harms detected on primary

review are reviewed by a trained physician,

who is the final arbiter

Severity of harm is rated using the modified

NCC MERP scale4

Aggregate measure of all-cause harm

Harms related to health care present on

admission, temporary harms, and

nonpreventable harms are included

Office of

Inspector

General

Harm

Detection

Method

Office of

Inspector

General,

adaptation

of the

Global

Trigger Tool

Adverse events: harm as a

result of medical care or

occurring in a health care

setting

2-Stage medical record review

Primary stage: records are screened for potential

adverse events using 5 methods, including a

modified version of the Global Trigger Tool’s

53 triggers

Secondary stage: full record review by a physician

team to confirm harm in flagged records and

assessment of the preventability and severity

of harms

Aggregate measure of all-cause harm

Temporary harms, nonpreventable

harms, and harms present on

admission excluded from

overall rate.

Abbreviations: AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision,

Clinical Modification; NCC MERP, National Coordinating Council for Medical Errors Reporting and Prevention; PSI, Patient Safety Indicator.

improvement opportunities. For example, voluntary reporting supplements formal assessment of harm rates by providing valuable information regarding near misses and failureprone systems, while promoting a culture of safety. Morbidity

and mortality reviews, executive walk-rounds, root-cause

analyses, and failure modes and effects analyses can yield

important clues to improving hazardous systems.

Conclusions

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the AHRQ

are well positioned to speedily clarify which measures and

methods can most effectively evaluate progress toward the

P4P goals. Until then, despite its imperfections, the Office

of the Inspector General approach may be the best available method for determining national harm trends.

While awaiting consensus, individual hospitals can apply a portfolio of measurement methods, including those

outlined in this Viewpoint, according to their own safety

priorities. Condition-specific measures (including Patient

Safety Indicators and real-time surveillance of specific harms)

are valuable for within-organization improvement. However, hospitals will need to address multiple types of harm

before substantial improvement in all-cause harm rates will

be observed. Delay in measuring the effect of best practices

on harm rates will postpone the day when the nation can

celebrate significant improvement in patient safety.

2156

JAMA, May 23/30, 2012—Vol 307, No. 20

Corrected on June 5, 2012

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the

ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Disclaimer: The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the Global

Trigger Tool and provides training materials at no charge.

Additional Contributions: We thank Carol Haraden, PhD, and Frank Federico, RPH,

both of the IHI, for their valuable comments and suggestions on this article. Neither were compensated for their contribution.

REFERENCES

1. Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ.

Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med.

2010;363(22):2124-2134.

2. Partnership for patients: better care, lower costs. healthcare.gov. http://www

.healthcare.gov/compare/partnership-for-patients. Updated December 14, 2011.

Accessed March 15, 2012.

3. Disclosure Working Group. Canadian Disclosure Guidelines. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Patient Safety Institute; 2008.

4. Medication errors council revises and expands index for categorizing errors: definitions of medication errors brroadened [news release]. National Cooridinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention; June 12, 2001. http://www

.nccmerp.org/press/press2001-06-12.html. Accessed May 2, 2012.

5. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370-376.

6. Metersky ML, Hunt DR, Kliman R, et al. Racial disparities in the frequency of

patient safety events. Med Care. 2011;49(5):504-510.

7. AHRQ Quality Indicators Toolkit for Hospitals. Agency for Healthcare and Research Quality; January 2012. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/qitoolkit/index.html. Accessed May 2, 2012.

8. Classen DC, Resar R, Griffin F, et al. “Global trigger tool” shows that adverse

events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health

Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):581-589.

9. Levinson DR. Adverse Events in Hospitals: National Incidence Among Medicare Beneficiaries. Washington, DC: Office of Inspector General; November 2010.

http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-09-00090.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

©2012 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Institute for Healthcare Improvement User on 04/10/2013