G Model

PEC-4423; No. of Pages 7

Patient Education and Counseling xxx (2012) xxx–xxx

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Patient Education and Counseling

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pateducou

Medical Decision Making

Combining deliberation and intuition in patient decision support

Marieke de Vries a,b,1,*, Angela Fagerlin c,d,e, Holly O. Witteman e,f,g, Laura D. Scherer c,e,h,1

a

Tilburg Institute for Behavioral Economics Research (TIBER), Department of Social Psychology, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands

Department of Medical Decision Making, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands

c

VA Ann Arbor Center for Clinical Management Research, Ann Arbor, USA

d

Division of General Internal Medicine and Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA

e

Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA

f

Vice-décanat à la pédagogie et au développement professionnel continu, Faculté de médecine, Université Laval, Quebec City, Canada

g

Département de médecine familiale et de médecine d’urgence, Faculté de médecine, Université Laval, Quebec City, Canada

h

University of Missouri, Department of Psychological Sciences, USA

b

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Article history:

Received 11 July 2012

Received in revised form 31 October 2012

Accepted 24 November 2012

Objective: To review the strengths and weaknesses of deliberative and intuitive processes in the context

of patient decision support and to discuss implications for decision aid (DA) design.

Methods: Conceptual review of the strengths and weaknesses of intuitive and analytical decision making

and applying these findings to the practice of DA design.

Results: DAs combine several important goals: providing information, helping to clarify treatment

related values, supporting preference construction processes, and facilitating more active engagement in

decision making. Many DAs encourage patients to approach a decision analytically, without solid

theoretical or empirical grounding for this approach. Existing research in other domains suggests that

both intuition and deliberation may support decision making. We discuss implications for patient

decision support and challenge researchers to determine when combining these processes leads to

better outcomes.

Conclusions: Intuitive and analytical decision processes may have complementary effects in achieving

the desired outcomes of patient decision support.

Practice implications: DA developers should be aware that tools solely targeted at supporting

deliberation may limit DA effectiveness and harm preference construction processes. Patients may

be better served by combined strategies that draw on the strengths and minimize the weaknesses of both

deliberative and intuitive processes.

ß 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Patient decision aids (DAs)

Values clarification methods (VCMs)

Preference construction

Decision making

Intuition

Deliberation

1. Introduction

1.1. Supporting patient decisions: current practices

In health care, individual treatment and screening decisions are

often preference sensitive, involving important trade-offs. For

example, available options can be equivalent in terms of medical

efficacy, but involve trade-offs between length and quality of life or

between comfort and efficacy of procedures. By taking individual

patient values into account, treatment and screening decisions can

be made so that they best fit an individual, with his/her unique

* Corresponding author at: Decision Psychologist, Tilburg Institute for Behavioral

Economics Research (TIBER), Department of Social Psychology, Tilburg University,

P.O. Box 90153, 5000 LE Tilburg, The Netherlands. Tel.: +31 13 466 8394;

fax: +31 13 466 2067.

E-mail address: MariekedeVries@TilburgUniversity.edu (M. de Vries).

1

Equal contribution.

situation, needs and desires [1–6]. However, putting this ideal into

practice is challenging. First, clinicians have been found to be

inaccurate at estimating patients’ values for health states [7] and

treatment options [8,9]. Moreover, in the novel, unanticipated, and

emotionally charged situations that many patients face, their

values and preferences are often labile or non-existent and need to

be clarified [10–12]. This clarification process can be complicated,

because potential outcomes and risks can be hard to verbalize and

imagine, and available options often involve trade-offs that make

them incommensurable [1,2].

In order to help patients make informed medical decisions that

reflect their personal values and circumstances, patient decision

aids (DAs) have become an increasingly common tool [5,6,13–17].

DAs combine several important goals, such as informing patients

about options, helping clarify patient values, supporting patients’

preference construction process, and enabling patients to more

actively engage in shared decision making with their health care

providers. DAs can, among other positive effects, enhance patients’

0738-3991/$ – see front matter ß 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.016

Please cite this article in press as: de Vries M, et al. Combining deliberation and intuition in patient decision support. Patient Educ Couns

(2012), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.016

G Model

PEC-4423; No. of Pages 7

2

M. de Vries et al. / Patient Education and Counseling xxx (2012) xxx–xxx

involvement in medical decisions [3,5,6], and increase patients’

knowledge and contentment with the decision-making process

[4,5]. Yet the effects of DAs on decision quality and process

measures (e.g., decisional conflict, feeling clear about one’s values)

are not consistent [5].

DAs often incorporate values clarification methods (VCMs) to

help elicit patients’ treatment values and help patients make

decisions. Many VCMs encourage patients to follow deliberative,

analytical processes in comparing available choice options,

suggesting an assumption on the part of developers that

deliberation is the preferable strategy for making medical

decisions [18]. This assumption has strong historical precedent,

but lacks a solid theoretical or empirical grounding, and is in

conflict with what we know about natural human reasoning and

action, which are not purely analytical and depend strongly on

intuition [19–30].

In the present article we argue that the effectiveness of DAs, and

of VCMs in particular, may be enhanced by drawing on the

strengths and minimizing the weaknesses of both deliberative as

well as intuitive decision processes. For the purposes of the present

article, deliberative decision processes are defined as effortful,

conscious and analytical and include decision strategies such as

making lists of pros and cons, as well as explicitly rating and

weighting these pros and cons. By contrast, intuitive processes are

defined as less effortful and less conscious processes. For example,

implicit and apparently effortless integration of available information can give rise to affective responses and gut feelings on which

intuitive decisions can be based. Such affectively-based decisions

are an important subset of intuitive decisions, but there are other

types of intuitive decision processes, such as the reliance on fastand-frugal heuristics, as we will discuss in more detail later [4,31–

33]. Whereas deliberative and intuitive processes are not always

entirely distinct, they clearly have been shown to have different

effects on decision making [4,33,34].

1.2. Intuition and deliberation in patient decision making

Evidence from psychological literatures suggests that at least in

some contexts, deliberation may interfere with decision making,

and intuitive decision strategies sometimes result in better

outcomes [19,21,34]. As we will outline in more detail below,

encouraging patients to extensively deliberate about their

personal preferences may have some unintended, potentially

harmful implications. Yet encouraging patients to deliberate also

serves important goals, such as supporting patients in taking a

more active role in the decision-making process with their health

care providers.

In order to understand how to design DAs and VCMs so that

they result in the intended outcomes, we underscore the need to

better understand the nature of intuitive and deliberative decision

processes that are involved in patient decision making, and that are

likely to be affected by the design of DAs and VCMs [1,5,16,18,35].

In the present article we aim to (a) provide an in-depth treatment

of this issue, as well as (b) clarify how existing research findings

can serve as a framework for developing hypotheses about how

these decision tools may influence outcomes.

2. Strengths and pitfalls of intuition and deliberation in patient

decision support

Throughout western intellectual history, the dominant view

has been that decisions are best made via analytical reasoning, and

that feelings interfere with good, rational decision making [36].

Indeed, ample evidence has shown that reliance on heuristic

processing or initial emotional reactions (e.g., fear, panic, anger)

can cause bias and error [37–39]. However, an influential body of

research also suggests that intuitions may be surprisingly accurate,

because they can be based on an implicit integration of a large

amount of information [4,19–24,32–34,40]. In fact, when it comes

to making important personal decisions, rational reasoning seems

to strongly depend on intuitive processes [19–24]. In the following

sections, we will review literature that illuminates both these

strengths and weaknesses of intuitive and deliberative decision

making strategies.

2.1. Deliberative decision making: taxonomy of strengths and pitfalls

2.1.1. Strengths of deliberation

Deliberation serves several important goals in decision

making. First, deliberation is likely to help people articulate their

preferences. Deliberation may empower patients by enhancing

their ability to engage in the shared decision-making process, and

communicate what they want to physicians [6]. Moreover,

deliberation may help decision-makers articulate reasons for

their preferences, which may reduce uncertainty and decisional

conflict, and help patients communicate why they have certain

preferences [5].

A second advantage of deliberation is that after people

analyze reasons for the values they find important, they act more

value-congruently. For example, when people are asked to

analyze their reasons for why they find the value ‘‘helpfulness’’

important, they later behave in a more helpful manner [41]. In

the context of patient decision support, this could cause patients

to make decisions that are more consistent with earlier-stated

preferences and values. However, as we will discuss in more

detail later on, the preferences that people report after

deliberative reasoning may systematically underweight attributes that are difficult to articulate, but that may nonetheless be

important to the decision at hand.

A third benefit of deliberation is that it may fit patients’

expectations about how health decisions should be made. When a

person feels good about how a decision is made, this can affect how

the person feels about the quality of the decision itself [33,42,43].

For example, when people believe that mental effort is required to

get the best decision outcome, they may interpret their exertion of

mental effort as a signal that an optimal decision has been achieved

[43]. This suggests that if a patient believes that deliberation is the

optimal strategy for the decision at hand, then deliberative

decisions will be viewed more favorably than intuitive decisions,

irrespective of the actual benefit of either strategy.

Finally, DAs are explicitly designed to encourage patients to

follow the logic of utilitarian decision-making, based on the

assumption that this will help patients to make decisions that

maximize utility. Hence, a fourth potential strength of encouraging

patients to deliberate in a DA is that this encourages them to

explicitly consider the likelihood of different outcomes and the

values they attach to these outcomes, and to decide based on a

logical integration of these. However, as outlined below, explicitly

considering and integrating likelihoods and values associated with

different outcomes is a complex and error-prone process that may

not only help, but also harm decision making.

2.1.2. Pitfalls of deliberation

A growing body of evidence shows that deliberation also has

several important limitations, and may even be harmful to

preference construction. First, in the choices patients face, some

choice attributes evoke strong immediate emotions, such as

feelings of anxiety or depression. When experiencing negative

emotions, subsequent thinking will be likely to be emotioncongruent, sustaining and possibly even intensifying these initial

negative emotional reactions [44,45]. For example, prolonged

elaborative processing when experiencing feelings of depression

Please cite this article in press as: de Vries M, et al. Combining deliberation and intuition in patient decision support. Patient Educ Couns

(2012), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.016

G Model

PEC-4423; No. of Pages 7

M. de Vries et al. / Patient Education and Counseling xxx (2012) xxx–xxx

can exacerbate depression, as this ruminative response allows

depressed feelings to bias thinking in an emotion-congruent way

[44]. Hence, a VCM that encourages patients to deliberate about

emotion-evoking information immediately after being exposed to

it may result in emotion-congruent thoughts, which may then

sustain or intensify the initial emotional response. Immediate

deliberation may thus overshadow other potentially important

choice attributes, such as the likelihoods of risks and benefits.

Interestingly, follow-up research has shown that distraction after

exposure to emotion-evoking stimuli can attenuate negative

feelings [46]. Later, we will discuss these findings’ potential

usefulness for DA design.

A second disadvantage of deliberation is that people are often

unaware of factors that influence their choices [19]. As a

consequence, when probed for reasons why they favor or disfavor

various options, patients may invent reasons that seem plausible,

but that are not correct. Moreover, people frequently fail to identify

the factors that actually do influence their choices. In one classic

psychological experiment [47] participants were asked to choose

from an array of identical stockings. Most people had a bias toward

choosing one of the right-most stockings. However, when asked

why they chose that particular stocking, none of the participants

realized that the position influenced their choice, and instead they

invented other reasons (e.g. ‘‘This one was the softest’’). This

phenomenon—given the apt title ‘‘Telling more than we can

know’’—is particularly relevant for patient decision making,

because it raises questions about patients’ ability to accurately

articulate the reasons for their preferences. If decision makers

cannot articulate the reasons for their preferences after a decision

is made, then asking patients to do so as part of the decision

making process could lead them to a decision they might not

otherwise make.

A third drawback of deliberation is that the act of verbalization

of reasons for one’s preferences can decrease decision satisfaction

and agreement between people’s judgments and expert opinions

[48–51]. Deliberation tends to cause people to focus on just a select

few reasons for choosing one option over another. Because of

failures of introspection, these reasons may not actually be the

most important, or even the real reasons for one’s preferences.

Instead, they are likely to be the reasons that are easiest to

articulate. As a result, deliberative reasoning can temporarily alter

one’s perception of which option is the best. This phenomenon has

been shown across a range of judgments, ranging from choices

between decorative posters to ratings of Olympic dives [48–51].

For example, in one experiment [48], students were brought into a

research laboratory and asked to view five posters and select one to

take home. Half of the students simply chose a poster, the rest were

instructed to list what they liked and disliked about each poster

prior to making their choice. Weeks later, the researchers

contacted the students and asked them whether the poster was

still on their wall. Students who chose the poster based on their

intuition were happier with their choice, and were more likely to

have it on their wall, than students who made lists. The

deliberative decision-makers chose posters on the basis of the

attributes that appeared on their lists, and these lists mostly

included attributes that were easy to articulate. Hence, participants’ lists biased them toward choosing the posters on the basis of

a particular attribute (e.g. humor) that was not related to longterm liking. This research suggests that deliberation can cause

people to disproportionally focus on attributes that are obvious,

accessible, and easy to articulate, but that are not necessarily most

important [4,19].

One corollary finding involving deliberation is that more

thought, and less reliance on emotive cues, leads to less stability

in preferences across time. That is, people tend to change their

mind more often when they deliberate [52,53]. Hence, when it

3

comes to preference-based decisions, deliberative strategies often

fail to arrive at judgments that consistently maximize utility.

2.1.3. Summary of the strengths and pitfalls of deliberative decision

making

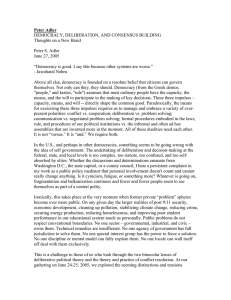

The second column of Table 1 represents an overview of the

above mentioned strengths and pitfalls of deliberation. In sum,

deliberation is likely to have several beneficial effects on decision

making: (1) it may help patients verbalize and articulate their

preferences and generate reasons for those preferences, (2) it may

help patients make decisions that are more congruent with their

stated preferences, (3) deliberation may help patients feel better

about how the decision was made, because it fits their expectations

about how such decisions ought to be made, and (4) it encourages

patients to explicitly consider the likelihood of different outcomes

and the values they attach to these outcomes, and to decide based

on a presumably logical integration of these. However, deliberative

strategies also possess a number of disadvantages, which together

suggest that deliberation does not always lead to a rational

integration of factual knowledge: (1) deliberative strategies may

cause emotion-congruent thoughts that intensify, rather than

abate, negative emotions, (2) they may cause patients to generate

reasons for their preferences that are inaccurate, and (3) they may

cause patients to focus on just a few salient treatment attributes,

and under-weight attributes that may be equally important but

more difficult to articulate.

2.2. Intuitive decision making: taxonomy of strengths and pitfalls

2.2.1. Strengths of intuition

Just like deliberation, intuitive processes also serve several

important goals in decision making, with some potentially

important implications for patient decision support. In particular,

over the past 20 years psychological evidence has shown that

compared to deliberative decision strategies, intuitive strategies

often result in better judgments and decisions, are more in line

with expert opinion, are more accurate, or result in higher

satisfaction [4,19,21,22].

The first advantage of intuitive decision making is that it is more

likely than deliberation to rely on automatic and/or unconscious

cognitive processes. Many of our mental processes take place

automatically, and in our everyday behavior we are largely

dependent on these automatic processes [20]. Importantly, these

processes are thought to be less limited in capacity than

deliberation, and therefore to be able to integrate larger amounts

of information [23,24,54–57]. Implicit integration of information

thereby results in a feeling toward various options that can reflect

the optimal choice with remarkable accuracy [23,24,41,55,57,58].

To illustrate this phenomenon, one study [40] asked participants to

view advertisements for an upcoming memory test. While viewing

the advertisements, information about stocks ran at the bottom of

a computer screen (stock information was irrelevant to the main

task). At the end of the experiment, participants were not able to

report which stock had the highest value, but when asked how

they felt toward each stock, their ratings accurately reflected the

actual stock value [40]. Such findings suggest that automatic

integration of information can result in feelings that do not

necessarily have a consciously accessible explanation but that are

nonetheless accurate [23,24,40,47,55].

Second, intuition may also provide an advantage in decision

making because compared to deliberation it is more sensitive to–

and better able to incorporate–feelings and affective cues in the

process of preference construction. That is, intuitive processing not

only results in feelings towards choice options in the form of

overall impressions of decision options, but it may also rely more

strongly on affective cues that can be of vital importance in

Please cite this article in press as: de Vries M, et al. Combining deliberation and intuition in patient decision support. Patient Educ Couns

(2012), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.016

G Model

PEC-4423; No. of Pages 7

M. de Vries et al. / Patient Education and Counseling xxx (2012) xxx–xxx

4

Table 1

Overview of decision maker goals, strengths and pitfalls of intuition and deliberation in preference construction and shared decision making and their implications for the

design of decision aids. Note: Goals, strengths, pitfalls and their implications are horizontally aligned.

Goals for decision making

Strengths and pitfalls of deliberation

Feeling good about decision

making process

Strength: fits expectations about

how medical decisions ought to be

made

Strength: may help to take all

relevant information into account

Acquiring all relevant information

Making decision congruent

with stated preferences, avoiding

heuristics and biases

Being able to explain preferences

and decision to others

Strength: facilitates decisions that

are congruent with stated

preferences (note that stated

preferences may not be accurate

due to faulty explicit reasoning)

Strength: facilitates verbalization

of preferences and reasons for

preferences

Incorporating all relevant attributes

into decision . . .

Pitfall: may focus attention on just

a few salient treatment attributes,

and under-weight attributes that

are difficult to articulate

. . . even if they are difficult to explain.

Pitfall: may cause patients to

generate inaccurate reasons for

their preferences

Avoiding making decisions in the

grip of strong emotions like fear

and panic.

Pitfall: intensification of negative

emotions

preference construction processes. Indeed, there is growing

acknowledgement that feelings and emotions are critical sources

of information for decision making [1,4,23,24]. As a classic

example, patients who have damage to the ventromedial

prefrontal cortex of the brain show impaired decision making,

in spite of having intact intellect and moral reasoning [58].

According to the ‘‘somatic marker hypothesis,’’ these patients have

deficits in emotional processing, and this emotion-specific deficit

makes it impossible to decide which option should be chosen, or

which course of action is best [24].

To illustrate this point empirically, researchers developed a

gambling task in which participants draw from four decks of

cards. On each draw, participants either lose or gain play money.

Two of the decks are stacked so that there are large gains, but also

large losses (the risky decks), resulting in a net loss of money. The

other two decks are stacked so that the gains are initially smaller

than those of the risky decks, but over time there is a net gain of

money, as losses are also smaller in these decks. Findings

consistently show that healthy participants learn to avoid the

risky decks, and show physiological signs of anxiety (e.g.

sweating) before drawing from that deck, even before they can

explicitly articulate why they prefer one deck over the other.

However, patients with damage to the prefrontal cortex do not

learn to avoid the risky decks, and show no physiological signs of

emotional distress when drawing from those decks. These

findings suggest that emotional cues, so called ‘‘somatic

markers’’ (e.g., sweating), can serve as an important signal for

making effective decisions [23,24]. Consistent with the idea that

affective cues can guide decision-making, it has recently been

proposed that affect may help patients make trade-offs between

options that are difficult to compare, such as choosing between

the quality versus quantity of life. In these situations, our

intuitive feelings help by serving as the ‘‘common currency’’

between logically incommensurable options [2].

Strengths and pitfalls of intuition

Potential implications for patient decision making support

Incorporate deliberative steps in

decision making support

Pitfall: may lead to uninformed

decisions when applied to early

stages of decision making, such as

information accrual

Pitfall: vulnerable to heuristics and

biases (but this may also be true of

deliberative strategies)

Encourage patients to become

informed and learn about each option

before making a decision

Pitfall: lacks logical-sounding

reasons and face validity that could

help to convince self and others

that decision is good

Strength: may rely on affective cues

that are based on larger amounts of

information and that weigh

information accurately, in spite of

lack of articulable reasons for those

feelings

Strength: may allow people to

compare options that are difficult

to compare using analytical

reasoning (i.e. provides a common

currency)

Encourage patients to articulate their

preferences for the purpose of

communicating to others

Present information so that heuristics

and biases are less likely to occur. Use

debiasing tools and strategies

Encourage patients to postpone

judgments, and instead form overall

impressions of all options first

Encourage patients to consider and

articulate their feelings, even if they

cannot provide reasons for those

feelings

Introduce distraction/delay to let

strong emotions abate prior to

deliberation

It is important to note that intuition serves as an umbrella

term, referring to the implicit and apparently effortless integration of information [4]. One example of automatic processing has

been widely influential—yet also highly controversial—in promoting intuition as an advantageous decision strategy. This

research suggests that after exposure to a decision problem, a brief

period of distraction can result in improved judgments and

decisions [59–62]. For example, in one experiment, participants

were asked to consider four hypothetical apartments, each of

which was described by twelve attributes [59]. One of the

apartments was an objectively better choice than the others, but

this best choice was not obvious, due to the large amount of

information presented. Participants who performed a distracting

task for a few minutes prior to their choice were more likely to

choose the objectively better apartment than participants who

deliberated and participants who decided immediately. This

effect has been labeled the Unconscious Thought Effect (UTE),

because it is assumed that the distracting task allows the

unconscious mind to integrate and weigh the relevant information. Yet a recent meta-analysis of 92 studies concluded that

distraction does not universally lead to better decisions. Instead,

distraction is most likely to lead to better decisions when the

decision is complex, when verbal and pictorial information

formats are combined, and when the information is ordered by

choice option rather than by attributes [62].

2.2.2. Pitfalls of intuition

Despite the importance of intuitive processes in decision

making, there are also some critical pitfalls associated with

reliance on intuition. First, decades of research have shown that

reliance on heuristic strategies and on strong, immediate

emotional reactions can cause bias and error in decision making

[38,39,63]. At this point there are countless biases that have been

documented in human judgment (e.g. recognition, framing,

Please cite this article in press as: de Vries M, et al. Combining deliberation and intuition in patient decision support. Patient Educ Couns

(2012), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.016

G Model

PEC-4423; No. of Pages 7

M. de Vries et al. / Patient Education and Counseling xxx (2012) xxx–xxx

anchoring, availability, conjunction fallacy, contrast effects), and

many of these biases have been attributed to failures of human

intuition. Consistent with this idea, research has shown that

the activation of deliberative processing can indeed reduce the

prevalence of various biases and heuristics [64]. However, some

heuristics (e.g. recognition) are actually more likely when

judgments are made deliberatively rather than intuitively [65].

Furthermore, although individuals who habitually use rational/

analytic processing are less likely to succumb to some types of

biases, they are equally—if not more—susceptible to other biases

[66–68]. In fact, recent evidence suggests that individuals who are

high in both rational and intuitive thinking styles are less

susceptible to heuristic biases than individuals who are highly

rational but not intuitive [69]. Hence, heuristics and biases are

indeed a disadvantage of intuition, but it appears that some biases

are not specific to intuition and rather are errors of human

judgment more generally.

A second disadvantage of intuitive decision strategies is that

they may make it difficult for patients to articulate the reasons for

their preferences. When patients lack plausible-sounding reasons

for their decisions, it may invite skepticism from health care

professionals, family and friends, or cause patients to feel

uncertain themselves.

Third, intuitive strategies may be more or less appropriate at

different stages of the decision making process. Recently, Pieterse

and De Vries [4] provided an analysis of the suitability of fast-andfrugal heuristics in the patient decision support context,

concluding that heuristics can be detrimental when they

encourage patient decision-makers to focus only on a subset of

the information provided in the DA. In other words, when fast,

intuitive strategies cause people to fail to acquire relevant

information, this can result in uninformed, poor decisions.

2.2.3. Summary of the strengths and pitfalls of intuitive decision

making

In this section, we reviewed theorizing and research addressing the strengths and pitfalls of intuition in preference

construction and decision making (see Table 1, third column,

for an overview). In sum, intuitive strategies have at least two

powerful advantages: (1) intuitive decisions are often based on

implicit information integration, which can integrate large

amounts of information and result in feelings that are surprisingly

accurate, and (2) intuitive decision making may be relatively more

influenced by, and dependent on, the presence of lower-order,

subtle affective cues. Indeed, the human mind seems to be wired

so that higher-order processes cannot function properly without

being grounded in lower-order, intuitive processes. However,

intuitive strategies also have a number of drawbacks: (1) they can

be influenced by heuristics and biases (but this may also be true of

deliberative strategies), (2) they lack logical-sounding reasons

that could help to convince others (and possibly also oneself) that

the decision is good, and (3) when intuitive strategies are applied

to early stages of decision making, such as information accrual,

they may lead to uninformed decisions.

3. Discussion and conclusion

3.1. Discussion: targeting intuition and deliberation in patient

decision support

A long-held assumption in patient decision making research is

that careful thought and reflection about medical choices should

lead to more positive outcomes, greater choice satisfaction, less

uncertainty, and less anxiety. Yet, our review of the decision

literature reveals a more nuanced picture. The evidence reviewed

in this paper suggests that deliberation may have intended

5

beneficial effects on facilitation of patient engagement. It also

encourages patients to become well-informed and follow the logic

of utilitarian decision-making. Patients may believe that deliberation is more appropriate than intuition, and therefore deliberation

may be viewed more favorably regardless of its actual effect on

decisions. However, deliberation can also produce biases and error

of its own: In particular, it can cause people to generate erroneous

reasoning which may negatively affect their preferences and

decisions, as well as cause people to focus on a few accessible

attributes that are not actually the most important. Our review of

the strengths and pitfalls of intuitive decision processes complements this picture. It indicates that, while heuristic processing and

reliance on strong, immediate emotional reactions can cause bias

and error, more sophisticated intuitive processes play a crucial role

in preference construction. Intuitive processes may allow people to

integrate larger amounts of information and to better use accurate

affective cues, thereby helping patients make difficult trade-offs

between dimensions that are hard to compare (e.g. the quality vs.

quantity of life; 1, 2, 4).

Some of the findings reviewed in this manuscript stem from

other research areas such as basic psychology and consumer

research. One objection to applying these findings to medical

decision making is that the decisions studied in basic research are

mostly simple and inconsequential consumer choices. Decision

processes in a consumer context may in some respects be

inherently different from choosing between medical options. For

example, medical decisions are sometimes made under distressing

conditions and can evoke strong emotions. Due to these strong

emotions these decisions are often avoided or approached in a

defensive manner. Even less dramatic medical decisions often

involve qualitatively different options than decisions made in a

consumer context. That is, unlike consumer choices where

decisions are being made about gains (i.e., goods or services a

consumer wishes to acquire), medical decisions typically involve

zero-gain or loss-minimizing options.

However, findings from other research areas nevertheless

illustrate important features of the architecture of the human

mind, such as how faulty reasoning can influence preference

construction, and how deliberation can focus attention on just a

few salient attributes. The existence of these psychological

processes calls into question the assumption that deliberative

thought necessarily renders optimal preferences and utilitymaximizing judgments. Moreover, these literatures suggest that

there are a number of counterintuitive ways in which intuitive

and deliberative thought modes influence decision making,

which are not yet fully realized in theoretical approaches to

decision aids. Even though medical decisions may indeed often

be more emotional than decisions that have been studied in other

contexts and involve zero-gain or loss-minimizing instead of

gain-maximizing options, we would still expect many of these

psychological phenomena to apply. For example, so long as the

less important decision attributes are easier to articulate than

the more important attributes, then we might expect that

deliberation can bias decision making. In fact, if anything, these

effects might be stronger when the situation is more emotionally

evocative, as deliberation may cause emotion-congruent

thoughts that intensify these emotions. Yet clearly future

research should investigate whether the same basic psychological mechanisms, for example, cause patients to disproportionally

focus on attributes that are emotionally evocative, salient, or

easy to articulate, overshadowing other important attributes to

the detriment of their eventual decision. The challenge,

therefore, is to gain a more fundamental understanding of

how we can support patients to be more engaged and informed

decision-makers, without causing unintended side-effects that

may harm their preference construction processes.

Please cite this article in press as: de Vries M, et al. Combining deliberation and intuition in patient decision support. Patient Educ Couns

(2012), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.016

G Model

PEC-4423; No. of Pages 7

M. de Vries et al. / Patient Education and Counseling xxx (2012) xxx–xxx

6

Together, the literatures that we reviewed suggest that both

intuition and deliberation are critical components in patient

decision making, but serve different goals in the patient decision

support context. Indeed, these processes might work best when

working together. Recently there has been evidence for precisely

this idea, insofar as experimental tests of the effects of intuitive

and deliberative decision strategies have shown that a combination of both resulted in the best decision outcomes [70]. It

could very well be the case that decision support is most

effective when it targets deliberative as well as intuitive

processes.

How can we combine the best of both intuition and

deliberation in patient decision making? In the right column

of Table 1, we provide an overview of potential implications for

patient decision support based on the identified strengths and

pitfalls of deliberation and intuition. The first two recommendations that follow from our analysis are already being implemented by DA developers: First, as many DA developers already

know, it is important to explicitly encourage patients to become

informed and learn about each option before making a decision.

This is because decision heuristics that are applied before

patients are informed are quite error-prone. Second, care should

be taken so that information is presented in such a way that

heuristics and biases are minimized. For example, people

generally have more favorable impressions of a treatment if

they learn it has a 90% survival rate rather than a 10% death rate

[71]. Hence, numerical information should be presented in both

formats (survival and death rates) in order to prevent this bias

from occurring.

Yet there are a number of additional and unique insights that

follow from the preceding review. First, although it may indeed be

helpful to encourage patients to articulate their preferences and

the reasons they have for their preferences, this exercise may be

better placed late in the decision process. This is because reasoning

about preferences early in the decision process (e.g. right after

exposure to new information) may be harmful to preference

construction, as it can focus attention away from decision

attributes that are relatively difficult to verbalize.

Second, when introduced too early, reasoning may cause bias

through the intensification of strong emotions evoked by the

content of the DA. Hence, patients could be encouraged (through

instructions in the DA) to delay making a decision and instead to

allow themselves to form more nuanced feelings and general

impressions of each of the options. Patients could benefit from

being encouraged to consider these overall impressions and

feelings about choice options, even if they cannot provide reasons

for them.

A third and related implication of this review is that a

distraction or delay could be useful after information has been

provided, because it could allow strong emotions to abate prior to

deliberation. This way, strong emotions that are linked to only a

part of the picture (e.g., fear for a potential outcome) would be less

likely to overshadow the rest of the decision.

3.2. Conclusion

The available findings reviewed here suggest that intuitive

and analytical decision processes have complementary effects in

achieving the desired outcomes of patient decision support. It is

our hope that this analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of

intuitive and deliberative decision processes, and their potential

implications for DA design, will contribute to the understanding

of how DAs—and VCMs in particular—can be designed and

evaluated. The ultimate goal is that DAs fit more closely with

how the human mind is naturally wired, resulting in increased

effectiveness.

3.3. Practice implications

DA developers should be aware that the current common

practice to encourage patients to extensively analyze available

choice options, typically immediately after information exposure,

lacks solid theoretical and empirical grounding. This practice may

limit potential DA effectiveness in supporting patient decision

making, and may even have some harmful side effects to

preference construction processes. Therefore, developers should

be encouraged to target, and evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of, both deliberative and intuitive decision processes, so

that future DAs and VCMs make the best use of all of patients’

decision making capabilities.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgements and funding

This work has been supported by an EASP Seedcorn Grant to

Marieke de Vries and Informed Medical Decisions Foundation

George Bennett Postdoctoral Grants to Laura Scherer and Holly

Witteman.

References

[1] Epstein RM, Peters E. Beyond information: exploring patients’ preferences. J

Am Med Assoc 2009;302:195–7.

[2] Kerstholt JH, van der Zwaard F, Bart H, Cremers A. Construction of health

preferences: a comparison of direct value assessment and personal narratives.

Med Decis Making 2009;29:513–20.

[3] Power TE, Swartzman LC, Robinson JW. Cognitive-emotional decision making

(CEDM): a framework of patient medical decision making. Patient Educ Couns

2010;83:163–9.

[4] Pieterse AH, De Vries M. On the suitability of fast and frugal heuristics for

designing values clarification methods in patient decision aids: a critical

analysis.

Health

Expect

2011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.13697625.2011.00720.x.

[5] Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Col NF, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, et al.

Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions (Review). Cochrane Collaboration 2011.

[6] Stiggelbout AM, Van der Weijden T, De Wit MP, Frosch D, Légaré F, Montori

VM, et al. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of

healthcare. Brit Med J 2012;344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e256 [published 27 January 2012].

[7] Cotler SJ, Patil R, McNutt RA, Speroff T, Banaad-Omiotek G, Ganger DR, et al.

Patients’ values for health states associated with hepatitis C and physicians’

estimates of those values. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:2730–6.

[8] Brothers TE, Cox MH, Robison JG, Elliott BM, Nietert P. Prospective decision

analysis modelling indicates that clinical decisions in vascular surgery often

fail to maximize patient expected utility. J Surg Res 2004;120:278–87.

[9] Fraenkel L, Bogardus ST, Concato J, Wittink DR. Treatment options in knee

osteoarthritis: the patient perspective. Arch Int Med 2004;164:1299–304.

[10] Fischhoff B. Value elicitation: is there anything in there? Am Psychol

1991;46:835–47.

[11] Simon D, Krawczyk DC, Bleicher A, Holyoak KJ. The transience of constructed

preferences. J Behav Decis Making 2008;21:1–14.

[12] Slovic P. The Construction of Preference. Am Psychol 1995;50:364–71.

[13] Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, Volk R, Edwards A, Coulter A, et al. Developing a

quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international

Delphi consensus process. Brit Med J 2006;333:417–21.

[14] Molenaar S, Sprangers MAG, Postma-Schuit FCE, Rutgers EJTh, Noorlander J,

Hendriks J, et al. Feasibility and effects of decision aids. Med Decis Making

2000;20:112–27.

[15] Bekker HL. The loss of reason in patient decision aid research: do checklists

damage the quality of informed choice interventions? Patient Educ Couns

2010;78:357–64.

[16] Duggan PS, Geller G, Cooper LA, Beach MC. The moral nature of patientcenteredness: is it ‘‘just the right thing to do’’? Patient Educ Couns

2006;62:271–6.

[17] Waljee JF, Rogers MAM, Alderman AK. Decision aids and breast cancer: do they

influence choice for surgery and knowledge of treatment options? J Clin Oncol

2007;25:1067–73.

[18] Nelson WL, Han PK, Fagerlin A, Stefanek M, Ubel PA. Rethinking the objectives

of decision aids: a call for conceptual clarity. Med Decis Making 2007;27:609–

18.

Please cite this article in press as: de Vries M, et al. Combining deliberation and intuition in patient decision support. Patient Educ Couns

(2012), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.016

G Model

PEC-4423; No. of Pages 7

M. de Vries et al. / Patient Education and Counseling xxx (2012) xxx–xxx

[19] Wilson TD. Strangers to ourselves: discovering the adaptive unconscious.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2002.

[20] Bargh JA. The automaticity of everyday life. In: Wyer SR, editor. Advances in

social cognition, vol. 10. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1997.

p. 1–61.

[21] Klein G. Intuition at work: why developing your gut instincts will make you

better at what you do. New York: Doubleday; 2003.

[22] Sadler-Smith E. Inside intuition. London: Routledge; 2008.

[23] Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR. Deciding advantageously before

knowing the advantageous strategy. Science 1997;275:1293–5.

[24] Damasio AR. Descartes’ error: emotion, reason, and the human brain. London:

Macmillan; 1994.

[25] Kahneman D. A perspective on judgment and choice: mapping bounded

rationality. Am Psychol 2003;58:697–720.

[26] Lee L, Amir O, Ariely D. In search of homo economicus: cognitive noise and the

role of emotion in preference consistency. J Consum Res 2009;36:173–87.

[27] Schwarz N, Clore GL. Feelings and phenomenal experiences. In: Higgins ET,

Kruglanski A, editors. Social psychology: handbook of basic principles. 2nd ed.,

New York: Guilford Press; 2007. p. 385–407.

[28] Zajonc RB. Feeling and thinking: preferences need no inferences. Am Psychol

1980;35:151–75.

[29] Damasio AR. Self comes to mind: constructing the conscious brain. New York:

Pantheon; 2010.

[30] Aarts H, Custers R, Marien H. Preparing and motivating behaviour outside of

awareness. Science 2008;319:1639.

[31] Betsch T. The nature of intuition and its neglect in research on judgment and

decision making. In: Plessner H, Betsch C, Betsch T, editors. Intuition in

judgment and decision making. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2008. p. 3–22.

[32] Glöckner A, Betsch T. Multiple-reason decision making based on automatic

processing. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 2008;34(5):1055–75.

[33] De Vries M, Holland RW, Witteman CLM. Fitting decisions: mood and intuitive

versus deliberative decision strategies. Cogn Emotion 2008;22(5):931–43.

[34] Hogarth RM. Deciding analytically or trusting your intuition? The advantages

and disadvantages of analytic and intuitive thought. In: Haberstroh S, Betsch

T, editors. The routines of decision making. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates, Inc; 2005.

[35] Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T, O’Brien MA. Treatment decision aids: conceptual

issues and future directions. Health Expect 2005;8:114–25.

[36] Von Neuman J, Morgenstern O. Theories of games and economic behavior.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1947.

[37] Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty – heuristics and biases.

Science 1974;185:1124–31.

[38] Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory – analysis of decision under risk.

Econometrica 1979;47:263–91.

[39] Loewenstein G. Out of control: visceral influences on behaviour. Organ Behav

Hum Decis Process 1996;65:272–92.

[40] Betsch T, Plessner H, Schwieren C, Gutig R. I like it but I don’t know why: a

value-account approach to implicit attitude formation. Pers Soc Psychol B

2001;27:242–53.

[41] Maio GR, Olson JM, Allen L, Bernard MM. Addressing discrepancies between

values and behaviour: the motivating effects of reasons. J Exp Soc Psychol

2001;37:104–17.

[42] Higgins ET, Idson LC, Freitas AL, Spiegel S, Molden DC. Transfer of value from

fit. J Person Soc Psychol 2003;75:617–38.

[43] Labroo AA, Kim S. The ‘‘Instrumentality’’ heuristic: why metacognitive difficulty is desirable during goal pursuit. Psychol Sci 2009;20:127–34.

[44] Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson BL. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. J Abnorm Psychol 1993;102:20–8.

[45] Siegle GJ, Steinhauer SR, Thase ME, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Can’t shake that

feeling: assessment of sustained event-related fMRI amygdala activity in

[46]

[47]

[48]

[49]

[50]

[51]

[52]

[53]

[54]

[55]

[56]

[57]

[58]

[59]

[60]

[61]

[62]

[63]

[64]

[65]

[66]

[67]

[68]

[69]

[70]

[71]

7

response to emotional information in depressed individuals. Biol Psychiat

2002;51:693–707.

Van Dillen L, Koole SL. Clearing the mind: a working memory model of

distraction from negative mood. Emotion 2007;7:715–23.

Nisbett RE, Wilson TD. Telling more than we can know: verbal reports on

mental processes. Psychol Rev 1977;84:231–59.

Wilson TD, Schooler JW. Thinking too much: introspection can reduce the

quality of preferences and decisions. J Pers Soc Psychol 1991;60:181–92.

Halberstadt J, Green J. Carryover effects of analytic thought on preference

quality. J Exp Soc Psychol 2008;44:1199–203.

Wilson TD, Dunn DS. Effects of introspection on attitude – behavior consistency: analyzing reasons versus focusing on feelings. J Exp Soc Psychol

1986;22:249–63.

Wilson TD, Hodges SD, LaFleur SJ. Effects of introspecting about reasons:

inferring attitudes from accessible thoughts. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995;69:16–

28.

Lee L, Amir O, Ariely D. In search of homo economicus: cognitive noise and the

role or emotion in preference consistency. J Cons Res 2009;36:173–87.

Nordgren LF. The devil is in the deliberation: thinking too much reduces

preference consistency. J Cons Res 2009;36:39–46.

Nørretranders T. The user illusion: cutting consciousness down to size. New

York: Viking; 1998.

Dijksterhuis A, Nordgren LF. A theory of unconscious thought. Psychol Sci

2006;1:95–109.

Lewicki P, Hill T, Bizot E. Acquisition of procedural knowledge about a pattern

of stimuli that cannot be articulated. Cogn Psychol 1988;20:24–37.

Betsch T, Glöckner A. Intuition in judgment and decision making: extensive

thinking without effort. Psychol Inq 2010;21:279–94.

Damasio AR. Emotion and reason in the future of human life. In: Cartledge B,

editor. Mind, brain, and the environment: the Linacre Lectures 1995-6. New

York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 57–71.

Dijksterhuis A. Think different: the merits of unconscious thought in preference development and decision making. J Person Soc Psychol 2004;87:586–98.

Dijksterhuis A, Bos MW, Nordgren LF, Van Baaren RB. On making the right

choice: the deliberation-without-attention effect. Science 2006;311:1005–7.

De Vries M, Witteman CLM, Holland RW, Dijksterhuis A. The unconscious

thought effect in clinical decision making: an example in diagnosis. Med Decis

Making 2010;30:578–81.

Strick M, Dijksterhuis A, Bos MW, Sjoerdsma A, van Baaren RB, Nordgren LF. A

meta-analysis on unconscious thought effects. Soc Cogn 2011;29:738–62.

Kahneman D. Thinking fast and slow. New York, NY: US, Farrar, Straus &

Giroux; 2011.

Alter AL, Oppenheimer DM, Epley N, Eyre RN. Overcoming intuition: metacognitive difficulty activates analytic reasoning. J Exp Psychol Gen

2007;136:569–76.

Hilberg BE, Scholl SG, Pohl RF. Think or blink – is the recognition heuristic an

‘‘intuitive’’ strategy? Judg Decis Making 2010;5:300–9.

Shiloh S, Salton E, Sharabi D. Individual differences in rational and intuitive

thinking styles as predictors of heuristic responses and framing effects. Pers

Indiv Differ 2002;32:415–27.

Stanovich KE, West RF. Individual differences in rational thought. J Exp Psychol

Gen 2008;127:161–88.

West RF, Meserve RJ, Stanovich KE. Cognitive sophistication does not attenuate the bias blind spot. J Pers Soc Psychol 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/

a0028857 [advance online publication].

Ayal S, Hochman G, Zakay D. Two sides of the same coin: Information

processing style and reverse biases. Judg Decis Making 2011;6:295–306.

Nordgren LF, Bos MW, Dijsterhuis A. The best of both worlds: integrating

conscious and unconscious thought best solves complex decisions. J Exp Soc

Psychol 2011;47:509–11.

McNeil BJ, Pauker SG, Sox HC, Tversky A. On the elicitation of preferences for

alternative therapies. N Engl J Med 1982;306:1259–62.

Please cite this article in press as: de Vries M, et al. Combining deliberation and intuition in patient decision support. Patient Educ Couns

(2012), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.016