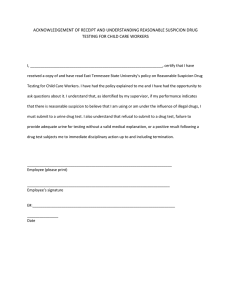

Yellow Rows of Test Tubes: Due Process Constraints on Discharges

advertisement