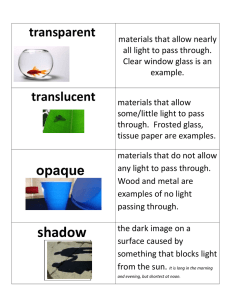

The combination of Glass and Ceramics as a

advertisement