Post-Sale Obligations of Product Manufacturers

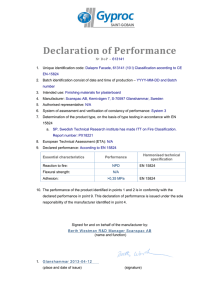

advertisement