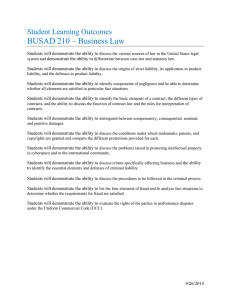

product law worldview

advertisement