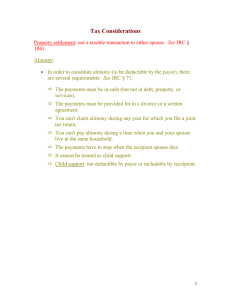

DIVORCE AND SEPARATION: TAX ISSUES By

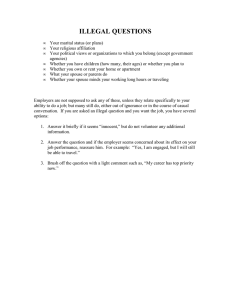

advertisement