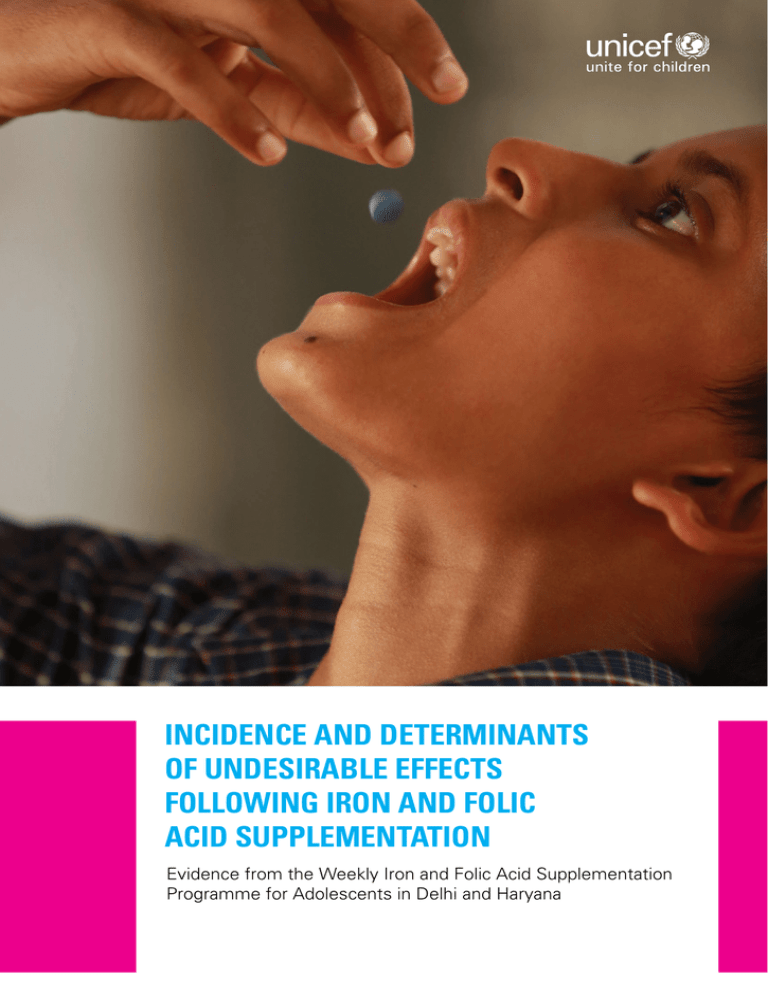

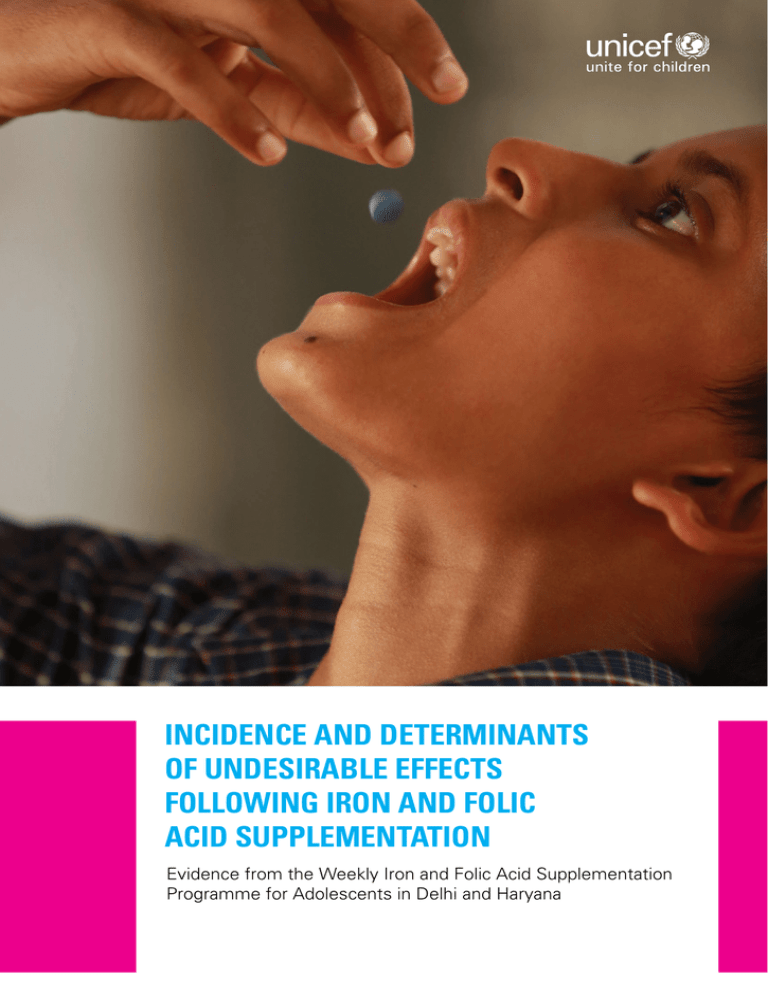

INCIDENCE AND DETERMINANTS

OF UNDESIRABLE EFFECTS

FOLLOWING IRON AND FOLIC

ACID SUPPLEMENTATION

Evidence from the Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

Programme for Adolescents in Delhi and Haryana

United Nations Children´s Fund

India Country Office

UNICEF House

73, Lodi Estate

New Delhi 110003

Telephone: +91 11 24690401

www.unicef.in

All rights reserved

©United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

2014

Cover photo: ©UNICEF India/Divakar Mani

Suggested citation: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Incidence and determinants

of undesirable effects following iron and folic acid supplementation. Evidence from the

Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation Programme for adolescents in Delhi and

Haryana. Nutrition Reports, Issue 3, 2014. New Delhi: UNICEF, 2014.

INCIDENCE AND DETERMINANTS

OF UNDESIRABLE EFFECTS

FOLLOWING IRON AND FOLIC

ACID SUPPLEMENTATION

Evidence from the Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

Programme for Adolescents in Delhi and Haryana

Nutrition Reports, Issue 3, 2014

Notice: This discussion paper is a part of the UNICEF India nutrition discussion paper series containing

preliminary material and research results. The nutrition discussion papers have been internally reviewed, but have not been subject to a formal external review. They are circulated in order to stimulate

discussion and critical comment. This discussion paper has been shared with the Adolescent Health

Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, on 7 February 2014.

CONTENTS

SUMMARY.................................................................. 5

Introduction.................................................................. 6

Methods....................................................................... 6

Results......................................................................... 7

Conclusion.................................................................... 8

REPORT...................................................................... 11

Introduction................................................................ 12

Methods..................................................................... 12

Results....................................................................... 16

Discussion.................................................................. 21

Conclusion.................................................................. 23

Literature cited........................................................... 25

STATISTICAL TABLES.............................................. 27

ANNEXES.................................................................. 45

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................50

©UNICEF India/Divakar Mani

SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

METHODS

In January 2013, the Ministry of Health and

Family Welfare (MHFW), Government of India,

launched the nationwide Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation (WIFS) programme.

The WIFS programme includes adolescent boys

and girls of Class VI–XII in government, government-aided and municipal schools. It also covers

out-of-school adolescent girls through the Integrated Child Development Services platform of

the Ministry of Women and Child Development.

The study was cross-sectional and conducted

across government schools in three districts

each in Delhi and Haryana that reported the

highest incidence of undesirable effects in May

2013 (Haryana) and July 2013 (Delhi). Thirty

schools from each state were selected utilizing

30-cluster Probability Proportional to Size (PPS)

methodology. In total, 4,183 adolescents (1,980

boys and 2,203 girls) from 60 schools were covered. Respondents were adolescent boys and

girls from Class VI-XII. However, as only Class

VI-VIII were covered in the WIFS programme in

Delhi, only these classes were covered in the

Delhi sample. Additionally, 49 nodal teachers

and 29 health providers were interviewed.

When WIFS roll-out began at state level, many

states reported that adolescents were complaining about undesirable effects after consuming iron folic acid tablets (IFA) and this

was hampering the programme significantly

through negative peer-to-peer pressure, mass

hysteria and media reports. The latter brought

the WIFS programme in Delhi and Haryana to

near standstill after the administration of the

first dose of WIFS in Haryana (in May 2013)

and in Delhi (in July 2013).

Upon the re-launch of WIFS in September 2013

in the two aforesaid states, upon request of

the MHFW, UNICEF India was commissioned

a study to answer the following four research

questions:

1. What is the incidence of undesirable effects

among school-going adolescent boys and

girls in Delhi and Haryana?

2. Do the adolescent boys and girls who experience an undesirable effect vs. those

who do not differ socio-demographically

and nutritionally?

3. Are schools and health providers prepared

to avert and manage undesirable effects?

4.What are the programme lapses that

can be avoided to improve WIFS programme performance?

6

Summary

The data collection period was 15-30 September 2013 in Haryana and 15-30 October 2013

in Delhi. Areas of enquiry included socio-demographic characteristics, consumption of iron folic

acid (IFA) tablets, protocol followed and undesirable effects on first consumption and in last

two consumptions. Nutritional status was ascertained through anthropometry – height, weight

and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC),

and height-for-age (HAZ) and body mass index

(BMI)-for-age z-scores were calculated using

World Health Organization Anthroplus software.

BMI-for-age z-score <-3SD was taken as severe

thinness and BMI-for-age z-score <-2SD as thinness. Similarly, HAZ score <-3SD was taken as

severe stunting and <-2SD as stunting. MUAC

cut-off of <16 cm and <18.5 cm were considered severely thin and thin respectively.

Dietary diversity was ascertained using a

seven-day qualitative food frequency questionnaire. Information on perceived gaps in IFA administration and suggestions to bridge the gaps

were collected from nodal teachers and medical

officers. Appropriate analysis was done using

STATA 12 (STATA Corporation, College Station,

TX, USA). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Tests of diagnostic accuracy were conducted to assess sensitivity and

specificity of MUAC compared to BMI-for-age

as the gold standard.

RESULTS

A total of 4,183 adolescents (1,980 boys and

2,203 girls) aged 10-19 years formed the analytical sample. The most important findings from

the study are summarized in this section.

RESEARCH QUESTION 1

What is the incidence of undesirable

effects among school-going adolescents

in Delhi and Haryana?

The incidence of undesirable effects following

IFA in the three weeks of WIFS administration

(week 1: first consumption; week 2 and 3: two

most recent consumptions) is discussed here.

In week 1, out of 4,183 adolescents who were

given IFA, 3,568 (85%) consumed IFA. Out of

the 3,568 adolescents who consumed an IFA

tablet, 907 (25%) reported that they faced an

undesirable effect. Importantly, 410 out of the

907 adolescents (45%) who faced an undesirable effect in week 1 did not consume IFA in the

subsequent week (week 2). Interestingly, 694

out of the 2,661 adolescents (26%) who did not

face any undesirable effect in week 1 did not

take IFA in week 2.

In week 2, again when IFA was administered to

all 4,183 adolescents, 2,630 (63%) reported that

they consumed IFA – a drop of 18 percentage

points in IFA consumption compared to 85% in

week 1. But out of those who consumed IFA

(n: 2,630), 7% reported an undesirable effect.

Again, 80 out of 194 (41%) adolescents who

faced an undesirable effect in week 2 did not

consume IFA in week 3. Also, 685 of the 2,435

adolescents (28%) who did not face an undesirable effect did not consume IFA in week 3.

In week 3 i.e., most recent consumption, again

IFA was administered to all 4,183 adolescents.

Out of these, 2,181 (52%) reported consuming

IFA – a drop of 24 percentage points from week

2, although an overall reported incidence of undesirable effects was 5%.

Thus, the incidence of undesirable effects

in week 1, 2 and 3 was 25%, 7% and 5%,

respectively. But the proportion of adoles-

cents consuming IFA gradually decreased

each subsequent week from 85% to 63% to

52% in week 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Importantly, 354 out of the 907 adolescents (39%)

who faced an undesirable effect on first consumption discontinued IFA. Taking all three

weeks, 1,050 adolescents faced an undesirable effect: 88% faced it only once, 8% twice

and only 4% faced an undesirable effect on

all three consumptions.

The types of undesirable effects were abdominal pain (80%), nausea (10%), dizziness (8%)

and fever (2%). Of the adolescents who reported undesirable effects two or more times –

90% had consumed the IFA tablet on an empty

stomach, 72% had chewed the tablet and 85%

had not had it with water. It is important to note

that 18% adolescents in the two states did not

eat anything before coming to school. Majority

of the adolescents (85% boys and 87% girls)

walked to school daily. The mean travel distance

to school was 1.7 km.

RESEARCH QUESTION 2

Do the adolescent boys and girls

who experience an undesirable effect

vs. those who do not differ sociodemographically and nutritionally?

The prevalence of thinness i.e., BMI-for-age

z-score <-2SD was 30% among boys and 23%

among girls. One quarter of adolescent boys

and girls were stunted (HAZ <-2SD). Multinomial regression analysis showed that the risk

of undesirable effects was higher in girls, in

lower classes (Class VI-VIII), and in urban residents, where parents, teachers and peers did

not encourage IFA consumption, and when IFA

was not consumed according to protocol. Having a BMI-for-age z-score <-2SD or HAZ <-2SD

or coming from a poorer family were not significantly associated with facing undesirable

effects. Adjusted binary logistic regression

showed that positive pressure from parents,

teachers and peers increased the odds of

full compliance (of IFA) by nearly twofold,

irrespective of the occurrence of an undesirable effect.

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

7

CONCLUSION

RESEARCH QUESTION 3

Are schools and health providers

prepared to avert and manage

undesirable effects?

In conclusion, undesirable effects significantly

hamper the WIFS programme but are not influenced by poverty or nutritional status. Particular

attention is to be paid to:

No. Half of the teachers interviewed in Haryana

and 5% teachers in Delhi did not receive training

before roll-out of the WIFS programme. On the

day of supplementation, only 43% teachers

discussed the protocol on how to consume

the tablet. In case of undesirable effects, 20%

schools did not have any designated official/

team to handle the undesirable effects. As a preparedness exercise to manage undesirable effects, 37% of schools had provision of common

medicines, in 29% schools the nodal teacher

had contact details of the Emergency Response

System team, and 20% teachers were aware

of the WIFS emergency toll free helpline

number, but none used it.

1. Constant positive reinforcement through

multiple channels and preparedness to

handle undesirable effects. Regular counselling by teachers and health providers to

parents and peers can improve IFA compliance. At school, information on benefits and

correct protocol should be disseminated

through loud speakers, posters and visually attractive educational sessions (possibly

through engagement of those who consume

IFA regularly and can advocate its benefits).

RESEARCH QUESTION 4

What are the programme lapses that

can be avoided to improve WIFS

programme performance?

Programmatic lapses identified in performance

of the WIFS programme as perceived by teachers and medical officers were: (i) suboptimal

training of teachers, (ii) teachers themselves

not being convinced of benefits of IFA administration, (iii) schools lacking ownership of the

programme, feeling it is the job of the Department of Health, (iv) ineffective convergence between Departments of Health and Education,

(v) inadequate positive media publicity and engaging with media only when an undesirable effect takes place, (vi) adolescents not liking the

taste (and taking it mostly because teachers

have asked them to), (vii) too much focus on

IFA rather than addressing anaemia, (viii) long

meal gaps for most adolescents, who mostly

came from deprived families (did not eat anything before coming to school and had a diet

which was poor in diversity), (ix) negative publicity by parents and peers after occurrence of

the undesirable effect, and (x) panic in schools

to manage undesirable effects.

8

Summary

At community level, informative television or

radio spots and positive messages through

youth icons may be considered for reaching out to adolescents and their families.

Use of mobile communication may also be

considered. Information to raise awareness

of helpline numbers, medicines and ‘WHAT

TO DO’ when there are reported undesirable effects should be displayed in schools,

and one day prior to IFA administration, all

arrangements for emergency response

should be re-checked by the emergency response team.

2.

Following WIFS protocol matters.

Majority of the adolescents who faced

undesirable effects were those who did not

follow the protocol. Hence, reinforcing the

protocol is important. Although nutritional

and socio-economic status did not influence

the occurrence of undesirable effects, given

that a large proportion of adolescents came

from deprived families, walked to school

and had a poor diet, provision of a nutrientdense snack to all adolescents may be

considered so that no adolescent consumes

IFA on an empty stomach. A nutrient-dense

snack will also bridge the calorie-protein

gap. Importantly, no adolescent should be

missed from WIFS if they are not covered

under the mid-day meal programme.

3. Convergence between Departments of

Health and Education needs strengthening. Inter-sectoral collaboration and

accountability mechanisms need to be

strengthened. Presently, a large proportion

of teachers have not received training on the

WIFS programme. If they have, they are not

equipped to manage undesirable effects and

do not own the programme.

4.Test alternative iron supplementation

methods. Compliance of IFA supplementation decreased each subsequent week

from 85% in week 1 to 52% in week 3. This

means that despite all effects, 48% of adolescents were not consuming the tablet in

week 3. These findings suggest the need for

experimenting more likeable energy dense

iron-rich food supplements, which not only

provide iron, but also bridge the gap in dietary macronutrient intake.

5. Ideally all schools should have World

Health Organization BMI-for-age charts

to assess progress on nutritional status.

Until then, MUAC appears as a reasonable

field alternative, subject to more diagnostic

accuracy studies in other settings.

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

9

©UNICEF India/Divakar Mani

REPORT

INTRODUCTION

Adolescent anaemia is a public health problem

in India. Every second adolescent girl and every

third adolescent boy is anaemic in India1. Given

the adverse consequences of adolescent anaemia on growth, resistance to infections, cognitive

development and work productivity, preventing

adolescent anaemia is a high priority agenda for

the Indian government2.

After 13 years of evidence generation by UNICEF

on the use of weekly iron and folic acid supplementation to address anaemia in adolescent girls

in different Indian states, the Ministry of Health

and Family Welfare (MHFW), Government of

India, launched a nationwide Weekly Iron and

Folic Acid Supplementation (WIFS) programme

in January 2013. The WIFS programme includes

both adolescent boys and girls enrolled in Class

VI–XII in government, government-aided and

municipal schools. It also covers ‘out-of-school’

adolescent girls through the Integrated Child Development Services platform of the Ministry of

Women and Child Development3.

The WIFS programme has four components:

1. Supervised WIFS comprising 100 mg of elemental iron and 500 mcg of folic acid (IFA).

2. Screening for moderate/severe anaemia and

referral to nearest health facility.

3. Deworming prophylaxis (400 mg albendazole) six months apart for the prevention of

helminthic infestations.

4.Monthly nutrition and health education

(NHE) to encourage consumption of locally

available iron-rich foods and prevent helminthic infestations.

Global research shows that there are unintended but expected mild undesirable effects

following IFA consumption. These include

gastrointestinal discomfort (stomach ache

and nausea) and change in the colour of stool.

Studies show that the proportion of adolescent girls who experience undesirable effects

following IFA consumption varies from 5% to

20%4. When the universal WIFS programme

roll-out began in various Indian states, state

programme managers in charge of the roll-out

12

Report

in many states reported that adolescents were

complaining about undesirable effects after

consuming iron and folic acid tablets and this

was hampering the programme significantly

through negative peer-to-peer pressure, mass

hysteria and media reports. The latter brought

the WIFS programme in the states of Delhi and

Haryana to near standstill after the administration of the first dose of IFA in May 2013 in Haryana and July 2013 in Delhi.

Questions arose among state programme managers whether adolescents who are weak socio-economically and nutritionally are more likely

to experience undesirable effects and should

the IFA dose be reduced for them. Upon the relaunch of WIFS in September 2013 in the two

aforesaid states, and upon request of the MHFW,

UNICEF India was commissioned a study to answer the following four research questions:

1. What is the incidence of undesirable effects among school-going adolescent boys

and girls?

2. Do the adolescent boys and girls who experience an undesirable effect vs. those

who do not differ socio-demographically

and nutritionally?

3. Are schools and health providers prepared to

avert and manage undesirable effects?

4. What are the programme lapses that can

be avoided to improve WIFS programme

performance?

METHODS

The present study was school-based, crosssectional and followed 30-cluster Probability

Proportional to Size (PPS) methodology.

Setting

States: The geographical scope of the study

was the National Capital Territory of Delhi and

Haryana – home to 5.3 million and 3.3 million

adolescent boys and girls, respectively5. Delhi

and Haryana were selected as they reported

the highest number of undesirable effects following administration of the first dose of IFA

after the launch of the WIFS programme in

these states (May 2013 in Haryana and July

2013 in Delhi).

institutions. The team was trained on the tools

and techniques used for data collection by the

UNICEF lead focal point for the study. The tools

were pre-tested on 5% of the sample in a school

in West Delhi.

Districts: In consultation with state governments and the national and state programme

teams of the WIFS programme, the top three

districts where the WIFS programme was operational in September 2013 and from where

the maximum number of undesirable effects

following the first dose of IFA supplementation

were reported in May 2013 (Haryana) and July

2013 (Delhi) were selected. In Delhi, the three

districts were West A, West B and South West

B. In Haryana, Hissar, Jind and Jhajjar districts

were chosen.

Respondents and sample size: A sample size

of 2,049 was calculated for each state using

maximum reported incidence of undesirable

effects of 20%3, relative precision of 15%,

95% confidence interval and design effect of

3 (see Annex 4). The respondents were adolescent boys and girls from Class VI-XII covered under the WIFS programme. Only Class

VI-VIII were included in the Delhi survey as

only these classes were covered in the WIFS

programme here. From each school (which is

considered as a cluster in the present study),

at least 70 adolescents were included. An attempt was made to include at least five boys

and girls from each class. Adolescents were

selected randomly from each class to complete minimum sample size.

Schools: The study was restricted to government schools, which fall under the jurisdiction

of the state government’s Directorate of Education, as majority of the undesirable effects were

reported from government schools. The list of

schools was obtained by the state Department

of Health and Family Welfare from the Directorate of Education. All the schools were enlisted

with their respective populations.

Thirty schools from each state were selected

utilizing the 30-cluster PPS method. The details of the 30-cluster PPS method are given

in Annex 1. The list of the 30 schools selected

from the two states is given in Annexes 2 and

3. Survey weeks were decided in consultation with district medical officers, the school

health programme division and school principal. However, the exact date was not told to

the school administration until the eve of data

collection to ensure accuracy in the collection.

Written consent from the school authorities

was taken prior to the survey.

Data collection

The nodal teacher of the WIFS programme from

each school and at least one primary health medical officer responsible for the Emergency Response System (ERS) for the block in which the

school was situated were also interviewed. In

total, 4,183 adolescents (1,980 boys and 2,203

girls) from 60 schools, 49 nodal teachers and 29

health providers formed the sample. The graphical presentation of research design is shown in

Figure 1. The data collection period was 15-30

September 2013 in Haryana and 15-30 October

2013 in Delhi.

Information

and

assessments:

Two

methods were used for collection of data

from the adolescents – interview method and

assessment of nutritional status using dietary

and anthropometric methods. Nodal teachers

and medical officers were interviewed using a

structured interview schedule and verbal consent

was taken from all the respondents.

The team: A team was formed comprising two

doctoral researchers trained in nutrition epidemiology and 15 postgraduate nutrition students

from the nutrition department of two academic

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

13

Information gathered from and

assessments conducted on adolescent

boys and girls

i. Adolescent characteristics: The information gathered included class, age (in completed years), residence (urban/rural), mode,

distance and time taken to reach the school,

and whether any form of employed work

(paid or unpaid) is carried out by the adolescent before/after coming to school. From adolescent girls, information on onset of menses, availability and use of sanitary pads,

availability of free sanitary pads in schools

(which were provided free of cost in Delhi)

and use of cotton/cloth during menses was

also collected.

ii. Family characteristics: The study included

information on the number of siblings, family size, education level and occupation of

mother and father. Household characteristics were also enquired and included source

of drinking water and toilet facility, material

of flooring and roof (as per definitions used

in India’s National Family Health Survey 31),

number of persons per sleeping room, availability of communication media like radio,

television, mobiles and computers, type

of cooking fuel used and availability of ration card.

iii.Anthropometry measurements6: Three

types of anthropometric measurements

– height, weight and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) were done on all the

adolescents.

Height was measured to nearest 0.1 cm

using a wall-mounted microtoise, nailed

on a wall with no or minimum skirting.

Adolescents stood barefoot on a flat floor

with heels together, calves, buttocks,

shoulder and head in one straight vertical

line touching the wall. They were asked to

keep legs straight and shoulders relaxed.

The head was comfortably positioned in

Frankfurt plane, that is, lower body of the

orbit of the eye in same horizontal plane

as the external canal of the ear and arms

hanging loosely on the sides. The head-

14

Report

piece of the microtoise was gently lowered and slight pressure was applied,

making contact with top of head to record

the height.

Weight was recorded to nearest 0.1 kg using an electronic weighing balance (TANITA

scale model no. H0358). Weight was taken

barefoot with minimal clothing while standing

straight on the weighing scale without any

support. Weighing scales were calibrated daily using standard weight of 1 and 5 kg before

taking the first observation.

Mid-upper arm circumference was

measured to nearest 0.1 cm using a nonstretchable standard MUAC tape (provided

by UNICEF). The left arm of the adolescent

was bent at the elbow at 90-degree angle,

with upper arm held parallel to the side

of the body. The distance between tip

of acromion and olecranon process was

measured and mid-point was marked. The

adolescent was then asked to let the arm

loose and the upper arm at the mid-point

was measured, making sure the tape was

not tight.

iv. Dietary assessment: A seven-day qualitative food frequency questionnaire was administered to assess consumption of foods

from different food groups, especially ironrich foods. The food frequency questionnaire

included nine food groups, namely, cereals

(including roots and tubers), dark green leafy

vegetables (DGLV), vitamin-C rich fruits, organ meats, meats, eggs, pulses and milk.

Each food group was assigned 1 score to

calculate the dietary diversity score (scores

were in the range of 0-9)7. Respondents

were enquired about the meal consumed

before coming to school on survey day.

v. IFA consumption, undesirable effects and

receipt of other services of the WIFS programme: Respondents were asked to recall

IFA administration of three weeks to determine the consumption pattern of IFA. Three

weeks included first consumption when the

programme was first initiated (May 2013 for

Haryana and July 2013 for Delhi) and last

Figure 1

Research design

States with highest prevalence of

undesirable effects

Delhi

Haryana

3 districts

West A

West B

South West B

3 districts

Hissar

Jind

Jhajjar

Maximum cases of

undesirable side effects

30 schools

Boys

(N=1,063)

Girls

(N=1,070)

30 schools

Boys

(N=917)

Teachers (N=22)

MO (N=13)

Girls

(N=1,133)

Teachers (N=27)

MO (N=16)

Interview with adolescents:

Socio-demographic profile, nutritional assessment, consumption pattern of IFA, incidence of

undesirable effects and benefits of IFA consumption.

Interview with MOs and teachers:

Emergency response system on occurrence of undesirable effects.

Data analysis

MS Excel (Office 10), WHO Anthroplus version 1.0.4,

SPSS version 16.0

Report writing

MO = medical officer

two consumptions from the day of enquiry

(September 2013 in Haryana and October

2013 in Delhi). Information on the WIFS protocol being followed, that is, IFA intake on

full stomach, swallowed with full glass of

water and supervised administration by the

nodal teacher was also collected.

The following information was collected on experience of undesirable effects after each of the

three IFA consumptions: type of undesirable effects and perceived reasons. Information was

also asked on reasons for consuming or not con-

suming the IFA tablet. Information was also collected about receipt of two other services under

the WIFS programme – receipt of biannual dose

of albendazole and monthly nutrition and health

education in school.

Interview with nodal teachers and

health providers

The nodal teacher responsible for IFA administration in each school (n: 49) and the medical

officer of the nearest Primary Health Centre/

Dispensary (n: 29) to the school responsible for

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

15

emergency response were interviewed. Data on

training received for IFA administration (teachers

only), protocol for IFA administration, reporting

of undesirable effects, preparedness for adverse effects and actions taken in case of undesirable effects were collected from teachers and

medical officers. Information on perceived gaps

in IFA administration and suggestions to bridge

those gaps were also collected.

(state, sex, residence and deprivation index), anthropometry (BMI-for-age z-score, HAZ, MUAC

less than 16 cm and 18.5 cm), dietary profile

(not eating anything before coming to school

and dietary diversity score), enabling factors for

IFA consumption (peer, parents’ and teachers’

influence), self-efficacy and protocols followed

for IFA consumption (supervised IFA consumption, full stomach, with water and swallowed).

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of the bivariate association was assessed using chi-square test. The

net association of undesirable effects with significant variables was examined in a step-wise

multinomial logistic regression. Associations

of compliance (intake of at least two IFA) with

socio-demographic characteristics, undesirable

effects and promoters of IFA consumption were

also studied using chi-square for bivariate and

multivariate logistic regression analysis. P values

<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The collected data were consolidated in Microsoft Excel (2007). The consolidated data were

rechecked for completeness and accuracy.

Height was used to calculate height-for-age

z-score (HAZ) and body mass index (BMI)-for-age

z-score was calculated using height and weight

measurements. World Health Organization Anthroplus (version 1.0.4)8 software was used for

calculating z-scores. BMI-for-age z-score cut-off

point of <-3SD was taken as severe thinness and

<-2SD as thinness (which included severe thinness). Similarly, HAZ cut-off point of <-3SD was

taken as severe stunting and <-2SD as stunting

(which included severe stunting). MUAC cut-off

of <16 cm and <18.5 cm were considered severely thin and thin, respectively9.

A multidimensional index of deprivation was

used to determine deprivation (proxy: for poverty). It included seven components – adolescent BMI-for-age z-score <-2SD, non-improved

drinking water facility, no toilet facility at home,

no access to health facility, illiteracy or less than

primary literacy among adolescents, ≥3 household members living in one room and no exposure to media, that is, non-availability of newspapers, radio, television, computers or mobiles

at home. Deprivation threshold score of 2-3 indicates moderate poverty and 4-7 indicates severe deprivation. Such a multidimensional index

of deprivation has been used elsewhere10.

Analysis was done using STATA 12 (STATA

Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). First,

standard univariate descriptive statistics were

calculated. Then, bivariate associations of undesirable effects (no undesirable effects, undesirable effects faced once and faced two or more

times) was done with adolescent characteristics

16

Report

To estimate the diagnostic accuracy between

BMI-for-age z-scores and MUAC, BMI-for-age

was considered as the gold standard and sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratios were calculated.

To compare agreement between the two methods, kappa statistic was calculated. Association

between the absolute values of BMI-for-age

z-scores and MUAC was determined by Pearson

correlation (r) method11.

RESULTS

All the 4,183 adolescents in Class VI to XII in the

study were included in the analysis. Of these,

1,980 were adolescent boys and 2,203 were

adolescent girls. In Delhi, the sampled adolescents were from Class VI-VIII, given that only

beneficiaries of the mid-day meal scheme were

given an IFA tablet. In Haryana, IFA was being

provided to adolescents in Class VI-XII.

1. What were the background

characteristics of the adolescents?

Table 1 describes the profile of the sampled

adolescents. Over 90% of the Haryana sam-

Figure 2

Mean BMI-for-age z-scores

10-12

13-15

16-19

Mean BMI-for-age z-score

-1.05

-1.1

-1.15

-1.2

n=2094

-1.25

-1.3

n=1632

-1.35

-1.4

n=457

Age range (in completed years)

ple resided in rural areas and nearly 90% of the

Delhi sample resided in urban areas. The majority of the adolescents (85% boys and 87%

girls) walked to school daily in both states.

The mean travel distance to school was 1.7 km.

Out of 4,183 adolescents, 88 (2%) also worked

in a job along with regular schooling. Of these

88 adolescents who worked, 56 (64%) worked

without pay.

Among adolescent girls, 41% had started menstruating (31% in Delhi and 50% in Haryana).

Out of the girls who started menstruating,

76% girls used sanitary napkins (96% in Delhi

and 64% in Haryana). In Delhi, 85% of the girls

were using sanitary napkins as they were available free of cost from school, under the School

Health Programme; no such programme was

operational in Haryana. In Haryana, 64% of

the girls used sanitary pads, while 36% used

cotton/cloth.

2. What were the socio-economic

characteristics of the adolescents?

About 50% of the mothers of the sampled

adolescents were illiterate and at least three

quarters of them were not engaged in working

outside the home. In contrast, most (≈60%) fa-

thers of the sample adolescents had received

education up to middle and higher level schooling and were engaged in skilled work. Homes

from where the adolescents came from were

mostly pucca or made of high quality (≈80%).

However, this proportion was lower in Haryana

(≈66%) compared to Delhi (≈90%). According

to the multidimensional index of deprivation, in

both states, three quarters adolescents were

from moderately deprived and 13% were from

severely deprived families (see Table 2).

3. What was the nutritional status of

the adolescents?

Thinness: The prevalence of thinness i.e.,

BMI-for-age z-score <-2SD was 30% among

boys and 23% among girls (see Table 3). The

sex-wise differences were starker in Delhi

(boys: 29% vs. girls: 19%) compared to Haryana (boys: 31% vs. girls: 26%). Over 9% boys

and 6% girls were severely thin i.e., BMI-forage z-score <-3SD. As age increased, mean

BMI-for-age z- score worsened (see Figure 2).

The prevalence of thinness and severe thinness also increased with increasing age (see

Table 4). As household deprivation increased,

mean BMI-for-age z-score also worsened

(see Figure 3).

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

17

Stunting: One quarter of adolescent boys

and girls were stunted (HAZ <-2SD) (see

Table 3). Proportion of severely stunted adolescents i.e., HAZ <-3SD was 6%. Stunting increased steeply from 9% in age of 10

years to 32% in age group of 18-19 years in

boys. Among girls, stunting was highest in the

age group of 11-12 years and 14 years (see

Table 4).

Identifying at-risk adolescents using MUAC:

Almost one third (29%) adolescent boys and

26% adolescent girls had a MUAC less than

18.5 cm. Proportion of adolescent boys and

girls with MUAC less than 16 cm was 7% and

6%, respectively.

Dietary pattern: Almost one fifth (18%)

adolescents in the two states did not eat

anything before coming to school (see Table

3). This proportion was higher in Haryana in

comparison to Delhi (21% vs. 16%) and higher

in girls compared to boys (23% vs. 13%). Not

even half of the sampled adolescents consumed

iron-rich foods twice a week. Diet diversity was

low, as 49% of the adolescents were consuming

fewer than three food groups in a day.

Consumption of eggs and meat twice a week

was also low (<15%). Meals chiefly comprised

a cereal and pulse/vegetable. Consumption of

DGLVs and vitamin C rich fruits at least twice a

week was 42% and 31%, respectively.

Diagnostic accuracy of MUAC compared to

BMI-for-age z-score (as gold standard): There

was agreement in 3,246 out of 4,183 (78%) observations of MUAC < 18.5 cm with BMI-forage z-score <-2SD. Kappa value of 0.34 (95% CI

0.31-0.38) showed a moderate agreement between the two tests. With BMI-for-age z-score

<-2SD as the gold standard, sensitivity and

specificity by MUAC <18.5 cm to correctly identify thinness (true-positive) and non-thinness

(true negative) was 73% and 79%, respectively

(see Table 5).

When MUAC <16 cm was compared with BMIfor-age z-score <-3SD (as gold standard), there

was agreement in 3,959 out of 4,183 (95%) observations, kappa value was 0.38 (95% CI 0.310.38) but sensitivity and specificity of MUAC

18

Report

<16 cm method to correctly identify severely

thinness (true-positive) and non-severely thinness (true negative) was 63% and 97% (see

Table 5). Taking absolute value of MUAC (in cm)

and BMI-for-age z-score, the power of association between MUAC and BMI-for-age z-score

was strong (r value of 0.68 (p<0.001)).

4. What was the IFA consumption and

compliance to protocol?

Table 6 describes the consumption pattern of IFA

during the first week of WIFS administration i.e.,

in May 2013 (Haryana) and July 2013 (Delhi) and

the last two weeks preceding the survey, a total

of three consumptions. The proportion of adolescents who consumed IFA only once, twice

and all three times were 23%, 26% and 42%,

respectively (see Table 6). The protocol for IFA

consumption is that it is to be supervised, after

a meal, with water and swallowed (not chewed).

Overall 43% adolescents reported supervised

IFA consumption (67% in Haryana and 47% in

Delhi). Percentage of adolescents consuming

IFA on an empty stomach was low, but higher

in Haryana compared to Delhi, and few but yet

more adolescents in Haryana chewed IFA than

in Delhi (see Table 6). Since the universal rollout of the WIFS programme, albendazole had

been given once in both states, and it was consumed by two thirds of the adolescents. One

third of adolescent girls mentioned receiving at

least one nutrition and health education session.

Attendance in NHE was higher in Haryana compared to Delhi (37% vs. 27%) and higher in girls

compared to boys (34% vs. 29%).

5. What was the incidence of

undesirable effects following

IFA consumption?

The incidence of undesirable effects in each of

the three weeks of WIFS administration (week

1: first consumption, week 2 and week 3 i.e.,

two most recent consumptions) is presented in

Table 7.

In week 1, out of 4,183 adolescents who were

given IFA, 3,568 (85%) consumed IFA. Out of

the 3,568 adolescents who consumed an IFA

Figure 3

Association of BMI-for-age z-score with multidimensional index of poverty

Non-poor

Moderately poor

Severely poor

Mean BMI-for-age z-score

0

-0.5

-0.6

-1

-1.2

-1.5

-2

-2.1

-2.5

Multidimensional index of poverty

tablet, 907 (25%) reported that they faced an

undesirable effect. Interestingly, 410 out of

the 907 adolescents (45%) who faced an undesirable effect in week 1 did not consume

IFA in the subsequent week (week 2). Also,

694 out of 2,661 adolescents (26%) who did

not even face any undesirable effect in week

1 did not take IFA in week 2, on influence of

their peers.

In week 2, again when IFA was administered to

all 4,183 adolescents, 2,630 (63%) reported that

they consumed IFA – a drop of 18 percentage

points in IFA consumption compared to 85% in

week 1. But out of those who consumed IFA

(n: 2,630), 7% reported to have faced an undesirable effect. Again, 80 out of 194 (41%) of

adolescents who faced an undesirable effect in

week 2 did not consume IFA in week 3. Also,

685 of the 2,435 adolescents (28%) who did not

face an undesirable effect did not consume IFA

in week 3.

In week 3 i.e., most recent consumption, again

IFA was administered to all 4,183 adolescents.

Out of these, 2,181 (52%) reported consuming

IFA – a drop of 24 percentage points from week

2, although the overall reported prevalence of

undesirable effects was only 5%.

Thus, incidence of undesirable effects in

week 1, 2 and 3 was 25%, 7% and 5%, respectively. But the proportion of adolescents

consuming IFA gradually decreased each subsequent week from 85% to 63% to 52% in

week 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Importantly, 410

out of the 907 adolescents (45%) who faced an

undesirable effect in week 1 did not consume

IFA in the subsequent week (week 2) and 354

of the 410 did not have IFA in week 3.

This means that 354 out of the 907 adolescents (39%) who faced an undesirable

effect on first consumption discontinued

taking IFA tablets. Taking all three weeks,

1,050 adolescents faced an undesirable effect: 88% faced it only once, 8% twice and

only 4% faced an undesirable effect on all

three consumptions.

The types of undesirable effects were abdominal pain (80%), nausea (10%), dizziness (8%)

and fever (2%). When the 1,050 adolescents

who faced an undesirable effect were asked

the perceived reasons for it (see Table 7), 37%

said because the body had not adjusted to the

tablet, 16% mentioned because they did not

follow the protocol and 2% mentioned that it

was due to menses.

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

19

6. What factors affected full compliance

of IFA?

Table 8 describes the characteristics of the

adolescents who demonstrated full IFA compliance (i.e., consumed IFA in all three weeks)

compared to those who consumed IFA either in

week 1 or 2. Full compliance was significantly

higher in Haryana compared to Delhi (53% vs.

47%, p<0.001), in girls compared to boys (54%

vs. 46%, p=0.04) and in rural compared to urban

adolescents (60% vs. 43%, p=0.001).

Adjusted binary logistic regression showed that

a high self-efficacy and positive pressure from

parents, teachers and peers increased the odds

of full compliance by 1.4-2.0-fold (see Table 8), irrespective of the occurrence of the undesirable

effect. High self-efficacy meant that the adolescents themselves felt that the tablet is beneficial

to them. Most commonly perceived benefits

were that they felt healthier (28%), felt energetic

(16%), and did not fall sick (17%) (see Table 9).

7. Did the adolescents who experienced

an undesirable effect vs. those who

did not differ socio-demographically

and nutritionally?

Table 10 shows the proportion of adolescents

who faced undesirable effects at least twice

significantly differed by state (2% in Delhi vs.

4% in Haryana, p=0.001), gender (32% in males

vs. 69% in females, p=0.001) and class (58% in

Class VI-VIII vs. 42% in Class IX-XII, p=0.001).

Having a BMI-for-age z-score <-2SD or HAZ

<-2SD or coming from a poorer family were

not significantly associated with facing undesirable effects two or more times. Regression analysis (see Table 12) confirmed that risk

of facing undesirable effects was twofold higher

in girls, in lower classes (Class VI-VIII), urban residents, where peers and parents did not encourage IFA consumption, and when IFA was not

consumed according to protocol.

8. Were teachers prepared to avert and

manage undesirable effects?

More than half of the teachers interviewed in

Haryana and 5% teachers in Delhi did not re-

20

Report

ceive training before roll-out of the WIFS programme (see Table 13). Twelve per cent of the

schools did not have a teacher designated as a

nodal teacher in-charge of the WIFS programme.

On the day of supplementation, only 43%

teachers discussed the protocol on how to

consume the tablet. In case of undesirable effects, 20% schools did not have any designated

official/team to handle the undesirable effects.

As a preparedness exercise to manage undesirable effects, 37% of schools had provision of

common medicines, in 29% schools the nodal

teacher had contact details of the ERS team,

and 20% teachers were aware of the WIFS

emergency toll free helpline number, but

none used it. In Haryana, there was no helpline

number.

9. Were health providers prepared

and equipped to manage

undesirable effects?

Approximately two thirds (66%) health providers interviewed reported that contact details of

hospitals and an ERS team were made available

to schools and common medicines were also

at the schools’ disposal (see Table 14). At least

80% of medical officers interviewed reported

that an ambulance was available on the day of

IFA administration in the health facility. The main

causes of undesirable effects amongst adolescents reported by medical officers were not following protocol (62%) and domino effect (48%).

Surprisingly, 59% of them felt that adolescents

who are undernourished or anaemic are more

likely to face an undesirable effect.

10.Which programme lapses could

have been avoided to improve

WIFS programme performance?

Programmatic lapses identified in the performance of the WIFS programme as perceived by

teachers and medical officers were:

i. suboptimal training of teachers;

ii. teachers themselves not being convinced of

benefits of IFA administration;

iii.schools lacking ownership of the programme, feeling it is the job of the Department of Health;

iv. ineffective convergence between Departments of Health and Education;

v. inadequate positive media publicity and engaging with media only when an undesirable effect takes place;

vi.adolescents not liking the taste (and taking it mostly because teachers have asked

them to rather than willingness to have

the tablet);

vii. too much focus on the IFA tablet instead of

raising awareness on the harms of anaemia and the role IFA consumption plays in

preventing anaemia.

viii. long meal gaps for most adolescents, who

mostly came from deprived families (did not

eat anything before coming to school and

had diet which was poor in diet diversity);

ix. negative publicity by parents and peers after occurrence of undesirable effects; and

x. lack of preparedness and panic in schools to

manage undesirable effects.

DISCUSSION

The 10 most important findings that emerged

from this study are discussed in this section.

1. In Delhi, adolescents in Class IX-XII

were not receiving WIFS.

After the re-launch of the WIFS programme in

September 2013, Delhi schools administrated

IFA to only Class VI-VIII (younger adolescents)

after the mid-day meal. IFA was not being distributed to adolescents in Class IX-XII, as it was

felt that older adolescents reported more undesirable effects and were more likely to take the

tablet on an empty stomach.

Programme implication:

According to NFHS-3, 56% girls and 30% boys

aged 15-19 years are anaemic in India1. Nonadministration of IFA in Class IX-XII misses a

large number of anaemic girls aged 15-19 years,

who should be provided WIFS.

2. Nearly one fifth of adolescents (23%

girls and 13% boys) did not eat

anything before coming to school

and 85% adolescents walked at least

1.5 km to school.

Nearly one fifth of adolescents came to school

on an empty stomach. In any case, the diets

consumed by the adolescents were sub-optimal

in diet diversity and low in iron-rich foods. Adolescents who reported not consuming anything

before coming to school were 1.2 times more

likely to report facing undesirable effects (OR

1.3, 95% CI 1.0-1.5). Also, 90% of adolescents

who reported experiencing undesirable effects

two or more times consumed the tablet on an

empty stomach.

Programme implication:

There is a need to sensitize adolescents on the

importance of eating before going to school.

Provision of a nutrient-dense snack to all adolescents may be considered so that no adolescent consumes IFA on an empty stomach. The

school assembly platform should be tapped to

spread awareness on the harms of anaemia and

benefits of IFA.

3. Incidence of undesirable effects

reduced gradually but adversely

affected compliance.

In the first consumption, 25% adolescents

faced an undesirable effect, which reduced to

7% and 5% in subsequent consumptions. The

most common undesirable effect was stomach

ache. However, the overall consumption of IFA

reduced from 85% in week 1 to 52% in week 3

due to negative media publicity, negative parental and peer pressure (which was more in urban

areas and among girls) and ill preparedness of

schools to manage undesirable effects. Importantly, 40% of adolescents who faced an undesirable effect in week 1 did not have IFA in week

2 and week 3.

Programme implication:

Regular IFA consumption reduces incidence

of undesirable effects as among those adolescents who consumed IFA and faced undesirable

effects, 88% faced them only once. However,

mass hysteria adversely affected WIFS in both

states and reduced the motivation among teachers and health providers who administer the tab-

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

21

lets. Focus on positive media publicity, and positive engagement of parents and peers needs to

be accelerated in the WIFS programme.

4. Reported undesirable effects were

higher among girls and urbanites.

The reported odds of undesirable effects were

twofold higher in girls compared to boys (adjusted OR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.5 to 3.3). Adolescents in rural areas were less likely to report

undesirable effects (adjusted OR 0.5, 95% CI

0.3-0.9).

Programme implication:

Adolescent girls who have benefited from IFA

should be encouraged to become peer monitors to motivate others. Positive video and audio communication materials may be played

through the school central speaker system and

through mass and mid media so that there is

a positive discussion and dialogue around addressing anaemia and the positive role of IFA

among peers, parents and providers.

5. Nutritional status was not a

predictor of undesirable effects.

One quarter of adolescents were stunted and

27% were thin (BMI-for-age z-score <-2SD).

Thinness, severe thinness and stunting were

not significantly associated with occurrence of

undesirable effects.

Programme implication:

Nutritional status of the adolescents does not affect the occurrence of undesirable effects. Thus,

there is no need to reduce the IFA dosage for

adolescents who are thin or stunted. However,

given that a large proportion of adolescents are

thin and stunted, there is a need to accelerate

measures for improving their nutritional status.

6. Socio-economic status was not a

predictor of undesirable effects.

According to the multidimensional deprivation

index, 87% school-going adolescents were

moderately/severely deprived. However, socioeconomic status did not emerge as a significant

predictor of undesirable effects.

22

Report

Programme implication:

Socio-economic status is not associated with

undesirable effects among adolescents. However, focus needs to be made on ensuring these

children receive a mid-morning snack as their dietary practices at home are poor.

7. Not following protocols was

a significant predictor of

undesirable effects.

Consumption of IFA without water (adjusted OR

16.4, CI 4.1-66.5), on an empty stomach (adjusted OR 50.3, CI 5.9-116.9) and chewing the

tablet (adjusted OR 4.03, CI 2.3-5.95) increased

the odds of facing undesirable effects.

Programme implication:

Not following WIFS protocols was a significant

predictor of undesirable effects. Worryingly,

in only 50% schools these protocols were reinforced on the day of administration of IFA.

Teachers should be instructed to repeat the protocols a day prior and on the day of administration of IFA. Provisions can be made to provide a

mid-day meal in case some adolescents forget

to bring lunch to school.

8. Schools were not prepared to avert

and manage undesirable effects.

One third of the teachers did not receive training before the roll-out of the WIFS programme.

Schools and teachers felt that the programme

was an added responsibility. More than half of

the schools did not reinforce the protocol while

administering IFA. Awareness of the helpline

number and its use, and disseminating important information about what do in the event of an

undesirable effect was very low.

Programme implications:

Collaboration with the Department of Education is essential to improve IFA administration, ensure nodal teachers are trained and

monitored to ensure undesirable effects are

averted and managed as well as ensure students are provided information on the types of

undesirable effects, counselled on what to do

and who to go to when such effects happen

to avoid panic.

CONCLUSION

9. Parental and peer pressure influenced

compliance and undesirable effects.

Negative parental and peer pressure increased

the odds of undesirable effects by at least threefold (OR 3.4, CI 2.3-5.1). Positive peer influence

increased compliance by 1.4 times (OR 1.4, CI

1.2-1.7) and also reduced the odds of reporting

undesirable effects (OR 0.6, CI 0.5-10). Both

these factors increased the self-efficacy of the

adolescent.

Programme implication:

Positive environment was identified as an important determinant for IFA consumption and

reducing undesirable effects. Parents and peers

should be made the focus of communication

strategies on IFA and informed about the benefits of IFA as well as possible undesirable effects

and their management.

10.MUAC appeared as a promising

field-based method for identifying

at-risk adolescents. More evidence is

needed on its use.

Kappa value of 0.34 (95% CI, 0.31-0.38) for

BMI-for-age z-score <-2SD and MUAC <18.5

cm and 0.38 (95% CI, 0.31-0.38) for BMI-forage z-score <-3SD and MUAC <16 cm showed

a moderate agreement between the two methods of assessing nutritional status, that is, BMI

(gold standard) and MUAC. Other studies comparing diagnostic accuracy of MUAC against

BMI also found that MUAC has a moderate to

good agreement with BMI12,13.

Programme implication:

In settings where weighing scales, height meters and BMI-for-age charts are not available,

simple methods such as MUAC may be used

to identify adolescents at risk and institute corrective measures for them. These may include

providing them an additional snack/supplement, enrolling them for extra diet and counselling sessions, which would include improving

dietary habits, confidence building and supplementary feeding.

In conclusion, undesirable effects significantly

hamper the WIFS programme but are not influenced by socio-economic or nutritional status.

Particular attention is to be paid to:

1. Positive reinforcement and preparedness

to handle undesirable effects matter.

Regular counselling by teachers and health

providers to parents and adolescents can

improve IFA compliance. At school, information should be disseminated through loud

speakers, posters and visually attractive

educational sessions (possibly through engagement of those who consume IFA regularly and can advocate its benefits).

At community level, informative television

or radio spots, through youth icons, may

be considered for reaching out to adolescents and their families. Information to raise

awareness on helpline numbers, medicines

and ‘WHAT TO DO’ when there are reported

undesirable effects should be displayed in

schools, and one day prior to IFA administration, all arrangements for emergency response should be re-checked by the emergency response team.

2. Following WIFS protocol matters. On the

day of IFA distribution, it is essential to ensure

that the adolescents have a meal before

consuming the IFA tablet. The availability

of safe water for swallowing IFA should be

ensured on school premises. Adolescents

should be informed about anaemia, the

positive benefits of IFA along with possible

undesirable effects, which may reduce with

subsequent IFA consumption.

Although nutritional status and socioeconomic status did not influence

undesirable effects, given that a large

proportion of adolescents came from

deprived families, walked to school and had

a poor diet, provision of a nutrient-dense

snack to all adolescents may be considered

so that no adolescent consumes IFA on an

empty stomach. There is a need to sensitize

adolescents on the importance of consuming

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

23

meals before going to school. All platforms

for promoting WIFS should also promote

improved dietary practices.

3.

Convergence between Departments

of Health and Education needs strengthening. Inter-sectoral collaboration and

accountability mechanisms need to be

strengthened at all levels. Presently a large

proportion of teachers have not received

training on WIFS. If they have, they are not

equipped to manage undesirable effects and

do not own the programme.

4.Test alternative iron supplementation

methods. Compliance of IFA supplementation decreased each subsequent week

from 85% in week 1 to 52% in week 3.

24

Report

This means that despite all effects, 48% of

adolescents were not consuming the tablet.

These findings suggest the need for experimenting to find more likeable energy dense

iron-rich food supplements, which not only

provide iron, but also supplement recommended macronutrients. Large-scale studies on efficacy, feasibility and effectiveness

of use of alternative food supplementation

products on haemoglobin levels are still to

be carried out.

5.Ideally all schools should have BMIfor-age charts to assess progress on

nutritional status. Until then, MUAC appears as a reasonable field alternative, subject to more diagnostic accuracy studies in

other settings.

LITERATURE CITED

1

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. National Family Health

Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences, 2007. http://www.

measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FRIND3/FRIND3-VOL2.pdf. Accessed 1 September 2013.

2

World Health Organization. Nutrition in adolescence – issues and challenges for the health sector.

Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241593660_

eng.pdf. Accessed 14 January 2014.

3

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Operational framework: weekly iron folic acid supplementation

programme for adolescents. New Delhi: Government of India, 2012. http://tripuranrhm.gov.in/Guidlines/

WIFS.pdf. Accessed 1 September 2013.

4

World Health Organization. Weekly iron and folic acid supplementation programmes for women of

reproductive age. An analysis of best programme practices. Geneva: World Health Organization,

2011. http://www.wpro.who.int/publications/docs/FORwebPDFFullVersionWIFS.pdf. Accessed 12

September 2013.

5

Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner India 2011. Census of India 2011: Provisional

Population Totals, India series. New Delhi: Government of India, 2011.

6

World Health Organization. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report WHO

Expert Committee. WHO Tech Rep Series 1995; 854: 1-452.

7

Food and Agriculture Organization. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity.

Rome: FAO, 2011. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/wa_workshop/docs/FAO-guidelines-dietarydiversity2011.pdf. Accessed 2 September 2013.

8

World Health Organization. WHO anthroplus: software for assessing growth of the world’s children and

adolescents. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009.

9

United Nations Standing Committee on Nutrition. Adults: assessment of nutritional status in emergencyaffected populations. Geneva: SCN, 2000.

10

United Nations. Expert group meeting on youth development indicators. Indicators of poverty and

hunger. New York: United Nations, 2005.

11

Landis RJ, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;

33: 159-174.

12

Dasgupta A, Butt A, Saha TK, Basu G, Chattopadhyay A, and Mukherjee A. Assessment of Malnutrition

Among Adolescents: Can BMI be Replaced by MUAC. Indian J Community Med. 2010 April; 35(2):

276–279.

13

Chakraborty R, Bose K, Koziel S. Use of mid-upper arm circumference in determining undernutrition

and illness in rural adult Oraon men of Gumla District, Jharkhand, India. Rural and Remote Health

2011: 1754.

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

25

©UNICEF India/Divakar Mani

STATISTICAL TABLES

Table 1

Sample population (column %)

Characteristics

Delhi

Haryana

Pooled

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

TOTAL

(N=1,063)

(N=1,070)

(N=917)

(N=1,133)

(N=1,980)

(N=2,203)

(N=4,183)

Class

6-8

9-12

100 100 58.7 54.5 80.3 76.7 78.6

# # 41.3 45.5 19.7 23.3 21.4

Residence

Rural

11.7 18.1 93.5 91.3 45.4 39.0 42.2

Urban

88.3 81.9 6.5 8.7 54.6 61.0 57.8

Adolescent characteristics

Distance

between school

and home

Mean (SD)

1.9 (1.4) 1.8 (1.5) 1.5 (1.7) 1.5 (1.5) 1.7 (1.6) 1.6 (1.5) 1.6 (1.5)

<1 km

10.8 9.8 30.4 27.7 19.9 19.0 19.5

1-2 km

80.0 81.5 62.3 65.2 71.8 73.1 72.4

3 km or more

9.2 8.7 7.3 7.1 8.3 7.9 8.1

Children

walking to

school

81.7 80.9 89.4 93.5 85.3 87.4 86.4

Children

working (n=88)

0.8 1.1 3.7 2.9 2.1 2.0 2.0

Paid work

33.3 33.3 38.2 36.4 34.9 37.8 36.5

Unpaid work

77.7 77.7 61.8 63.6 65.1 62.2 63.5

- 31.1 - 49.9 - 40.8 40.8

Sanitary

napkins

- 95.5 - 63.6 - 76.2 76.2

Free from

school

- 85.0 - - - 32.7 32.7

Purchased

- 10.5 - 63.6 - 43.5 43.5

Cloth

- 36.4 - 23.8 23.8

Illiterate

45.7 43.0 55.2 51.4 50.4 47.4 48.9

Primary

13.7 15.5 22.0 18.2 17.5 16.9 17.2

Middle or higher

40.6 41.5 22.8 30.4 32.1 35.7 33.9

Unemployed

79.2 77.0 78.0 77.8 78.8 75.7 77.3

Unskilled work

10.4 12.2 11.1 11.3 10.8 13.4 12.1

10.4

10.8

10.9

10.9

10.4

10.9

10.6

Menses

among girls

Started

Material used

during menses

(n=932)

4.5

Parental characteristics

Mother’s

education

Mother’s

occupation1

Skilled work

28

Statistical tables

Table 1

(cont.)

Characteristics

Delhi

Haryana

Pooled

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

TOTAL

(N=1,063)

(N=1,070)

(N=917)

(N=1,133)

(N=1,980)

(N=2,203)

(N=4,183)

Parental characteristics

Father’s

education

Illiterate

26.3 28.9 30.7 28.2 28.4 28.6 28.5

Primary

13.0 11.7 16.9 14.3 14.8 13.0 13.9

Middle or higher

60.7 59.4 52.4 57.5 56.8 58.4 57.6

Unemployed

6.1 9.8 10.4 9.6 7.9 9.6 8.8

Unskilled

work

34.1 33.1 42.6 39.0 38.0 36.1 37.0

Skilled work

59.8 57.1 47.7 51.4 54.1 60.4 57.2

Kaccha

9.0 7.1 34.5 30.3 20.8 19.0 19.9

Pucca

89.8 91.7 64.1 68.7 77.9 79.9 78.9

Semi-pucca

1.1 1.2 1.4 1.0 1.3 1.1 1.2

Father’s

occupation1

Housing

Housing

2

Adolescents of Class 9-12 were not receiving WIFS tablets in Delhi.

#

Derived from Kuppuswamy’s classification for occupation.

Houses made from mud, thatch, or other low quality materials are called kaccha houses, houses that use partly

low quality and partly high quality materials are called semi-pucca houses, and houses made with high quality

materials throughout, including the floor, roof and exterior walls, are called pucca houses.

1

2

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

29

Table 2

Multidimensional index of poverty1 (column %)

Household

characteristics

Delhi

Haryana

Pooled

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

TOTAL

(N=1,063)

(N=1,070)

(N=917)

(N=1,133)

(N=1,980)

(N=2,203)

(N=4,183)

BMI-for-age

z-score <-2SD

29.2 19.1 31.4 26.1 30.2 22.7 26.4

Non-improved

drinking water

facility2

30.6 28.2 24.7 19.0 27.8 23.5 25.7

No toilet facility at home

15.8 14.4 29.6 22.9 22.2 18.8 20.5

No access to

health facility

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

≥3 people

residing in one

room

77.3 80.5 70.9 74.0 74.3 77.2 75.8

Illiteracy

among

adolescents

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

Radio

13.9 16.4 10.8 13.9 12.5 15.1 13.8

Television

95.8 98.2 73.3 76.9 85.3 85.6 85.5

Mobile

97.7 97.9 90.8 91.4 94.5 94.1 94.3

Newspaper

17.4 17.1 11.9 13.2 14.9 15.1 15.0

Computer

5.3 6.1 0.9 2.3 3.1 4.2 3.7

Non-poor (0-1) 12.0 11.3 12.5 13.4 12.3 12.4 12.4

Moderate (2-3) 73.9 77.2 72.3 76.3 73.1 76.7 74.9

Severe (4-7)

14.1 11.5 15.2 10.3 14.6 10.9 12.8

Exposure to

media

Multidimensional index

of poverty

Includes seven components – BMI-for-age z-score <-2SD, drinking water facility, toilet facility at home, access

to health facility, illiteracy or less than primary literacy among adolescents, ≥3 household members living in one

room and exposure to media (newspapers, radio, television, computers or mobiles at home). Poverty threshold

score of 2-3 indicates moderate poverty and 4-7 indicates severe poverty.

2

Non-improved drinking water facility included unprotected dug well, unprotected spring, tanker truck/cart with

small tank and surface water.

1

30

Statistical tables

Table 3

Anthropometry and dietary status of sample population (column %)

Characteristics

Delhi

Haryana

Pooled

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

TOTAL

(N=1,063)

(N=1,070)

(N=917)

(N=1,133)

(N=1,980)

(N=2,203)

(N=4,183)

BMI-for-age

z-score

Thin <-2SD1

29.2 19.1 31.4 26.1 30.2 22.7 26.5

Severely thin

<-3SD

10.2 5.5 8.6 6.2 9.4 5.8 7.6

Over nourished >2SD

0.9 1.1 0.0 0.3 0.5 0.6 0.6

65.8 74.8 67.4 72.2 66.5 73.4 70.0

Moderately

thin

41.7 34.1 32.1 30.1 37.3 32.0 34.7

Severely thin2

<16 cm

9.0 6.3 7.2 6.6 8.2 6.4 7.3

25.3 31.1 23.4 22.0 24.4 26.4 25.4

Severely

stunted <-3SD

7.1 9.7 4.7 3.9 6.0 6.5 6.3

9.5 22.9 17.8 23.1 13.3 23.0 18.2

Pulses or

beans

90.5 90.5 69.3 66.1 80.7 77.9 79.3

Dark GLVs

56.4 50.6 28.8 28.9 43.6 39.4 41.5

Vitamin C rich

fruit

39.2 40.4 21.4 23.5 31.0 31.7 31.3

Eggs

23.7 19.7 3.5 0.5 14.3 9.9 12.1

Fish/chicken/

meat

15.5 12.9 0.4 0.4 8.5 6.5 7.5

<3 food groups 46.1 47.7 48.2 51.6 47.1 49.8 48.5

3-5 food

groups

53.6 51.6 51.8 48.4 52.8 49.9 51.4

6-9 food

groups

0.3 0.7 - - 0.1 0.3 0.2

Normal ≤2SD

& ≥-2SD

MUAC

Height-for-age

z-score

Stunted

<-2SD1

Ate nothing

before coming

to school on

survey day

Iron-rich food

consumed

twice weekly

Dietary

diversity3

Includes children who are below -3SD from the WHO international growth standard median.

Includes children who have values below 18.5 cm.

3

Nine food groups include consumption of cereals, dark green leafy vegetables (GLVs), vitamin A rich foods,

fruits, organ meats, meats, eggs, pulses and milk in past 24-hour recall.

1

2

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

31

Table 4

Distribution of the sample population by age and sex (row %)

Agewise

distribution

(completed years)

BMI-for-age

Height-for-age

z-score

z-score

N

<-2SD

<-3SD

<-2SD

<-3SD

MUAC

<18.5 cm

<16 cm

10

Boys

131

19.1

5.3

9.2

0.8

66.4

18.3

Girls

195

17.4

4.6

20.5

4.6

61.5

11.8

Boys

393

24.4

5.3

15.8

5.3

53.7

Girls

455

25.9

7.2

28.4

7.3

52.7

10.5

Boys

473

29.8

9.9

25.5

9.9

44.0

8.7

Girls

447

25.3

5.4

29.1

5.4

34.9

6.5

Boys

423

32.6

11.6

30.0

11.6

33.3

7.8

Girls

400

23.5

6.0

26.5

6.0

24.7

4.5

Boys

239

35.6

11.7

31.0

11.7

23.8

7.5

Girls

251

18.7

4.8

31.9

4.8

16.7

3.2

Boys

147

40.1

12.2

29.3

12.2

13.6

4.8

Girls

172

18.0

4.1

19.8

4.1

10.5

3.5

Boys

89

30.3

6.7

25.8

6.7

7.9

2.2

Girls

143

23.1

8.4

21.0

8.4

11.2

3.5

Boys

48

33.3

14.6

25.0

14.6

10.4

4.2

Girls

85

23.5

5.9

23.5

5.9

11.8

2.4

Boys

37

32.4

10.8

32.4

5.4

5.4

2.7

Girls

55

18.2

5.5

23.6

-

9.1

5.5

Boys

1,980

30.2

9.4

24.8

8.9

28.7

7.2

Girls

2,203

22.7

5.8

24.9

6.5

25.9

6.4

TOTAL

4,183

26.5

7.6

24.9

7.7

27.3

6.8

11

8.7

12

13

14

15

16

17

18-19

10-19

32

Statistical tables

Table 5

Diagnostic accuracy of MUAC in identifying thinness

BMI method

(Gold standard)

BMI <-2SD

Undernourished

BMI ≥-2 SD

Non-undernourished

Total

MUAC method

Prevalence

Sensitivity

= 26.2%

= 73.4%

Specificity

= 79.2%

Positive (<18.5 cm)

Undernourished

803 (True +ve)

641(False +ve)

1444

PV+

PV-

= 55.6%

= 89.4%

Negative (≥18.5 cm)

Non-undernourished

296 (False –ve)

2443 (True –ve)

2739

LR+

LR-

= 3.53

= 0.34 (95%

CI 0.31-0.38)

Total

1099

3084

BMI <-3SD

Undernourished

BMI ≥-3 SD

Non-undernourished

Total

Prevalence

Sensitivity

= 7.6%

= 62.6%

Specificity

= 97.3%

MUAC method

Positive (<16 cm)

Undernourished

198 (True +ve)

106 (False +ve)

304

PV+

PV-

= 63.2%

= 97%

Negative (≥16 cm)

Non-undernourished

118 (False –ve)

3761 (True –ve)

3879

LR+

LR-

= 33.9

= 0.38 (95%

CI 0.31-0.38)

Total

316

3867

Incidence and Determinants of Undesirable Effects following Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation

33

Table 6

Consumption pattern of IFA in sample population of last three weeks from date of study (column %)

Characteristics

Delhi

Haryana

Pooled

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

Boys

Girls

TOTAL

(N=1,063)

(N=1,070)

(N=917)

(N=1,133)

(N=1,980)

(N=2,203)

(N=4,183)

91.1 92.5 90.8 86.8 90.9 89.6 90.3

Never (0)

8.9 7.5 9.2 13.2 9.0 10.4 9.7

Once

24.9 17.9 20.5 26.0 22.9 22.1 22.5

Twice

32.1 30.7 21.3 17.7 27.1 24.1 25.6

All three times

34.1 43.9 49.0 43.1 41.0 43.4 42.2

Supervised IFA

consumption

43.8 50.4 69.8 65.4 44.1 41.9 43.0

NHE session in

past 2 weeks

23.5 30.2 34.9 37.8 28.8 34.1 31.5

Albendazole

consumption

65.2 65.5 63.4 62.3 64.4 63.9 64.2

IFA consumed at

least once