TEMPERATURE OF SCOTTISH LAKES 113 depends solely upon

advertisement

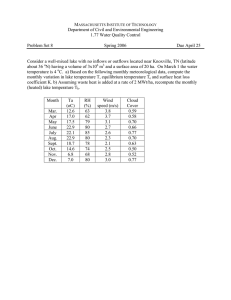

TEMPERATURE OF SCOTTISH LAKES 113 depends solely upon the water reaching its maximum density point ; but when that point is reached, the water is in a condition which makes freezing possible. Before that point is reached, water cooled by contact with the air or otherwise is heavier than the water immediately below it, and accordingly it sinks until it is mixed with the water through which it falls, or until it reaches water of equal density. In this way warm water is always brought to the surface, and freezing is practically impossible. But when the maximum density point has been reached, the water which is cooled at the surface no longer sinks. Its tendency is to remain at the surface, and as the rate of conduction in water is small, freezing will readily take place in water at and below the maximum density point. It is possible for some of the water in a lake to be above the maximum density point while the remainder is below. Fig. 40 shows the temperature distribution to be found in such a case. There are not many actual observations of such a temperature distribution recorded, but it is a matter of common observation that shallow bays in a lake, which as a whole is very seldom covered with ice, may freeze over readily ; and in most cases this means that, while the bulk of the water in the lake is above the maximum density point, there is water round the shores that has been cooled below that point. As a matter of fact, however, the water in a lake is usually cooled considerably below the maximum density point before freezing takes place. There is usually a lapse of time between the date at which the water in the lake has been cooled to the maximum density point and the date at which the air temperature falls below freezing point. During this time the water in the lake is gradually falling in temperature, and owing to the circulation of the water produced by the wind, the whole body of water contained in the lake, and not merely the surface layer, falls in temperature. Thus Buchanan found that the mean temperature of the water under the ice in Loch Lomond was 34° Fahr., or about 5° below the maximum density point, and in Linlithgow Loch 37° Fahr. Freezing takes place most readily in cairn weather, as the effect of winds and storms is to mix the water cooled at the surface with the water below it. At times the freezing takes place all over the surface of the lake in one night, while at other times it begins at the shores, and the ice gradually creeps in to the centre of the lake. This latter is the manner in which lakes with shallow shores freeze. As previously explained, the water round about shallow shores cools more rapidly than the water in the centre of the lake, and so freezes more readily. When once a fringe of ice has formed round the shores, there are set up convection currents from the shore towards the 8