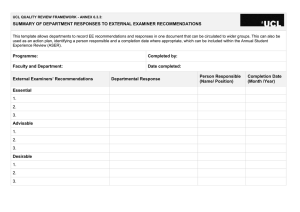

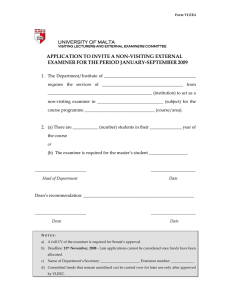

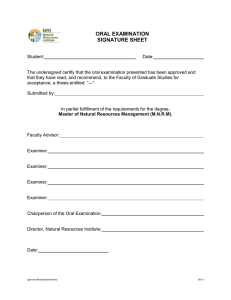

A handbook for external examining

advertisement