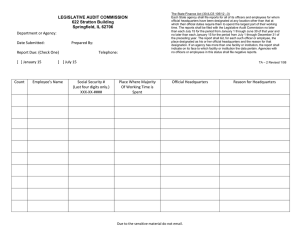

The Size and Composition of Corporate Headquarters in

advertisement