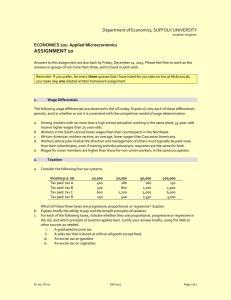

Economics in One Lesson

advertisement