Why you can safely ignore Six Sigma Fortune 2001

advertisement

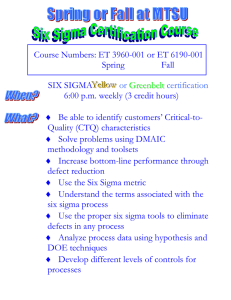

Why you can safely ignore Six Sigma Fortune January 2001 Abstract: Six Sigma, and a couple of similar-looking knockoffs, are nothing short of a full-on corporate fad, the latest in a long line of must-have efficiency crazes that perpetually spread through corporate America. Fueled in large part by GE CEO Jack Welch-who frequently talks it up to the media-companies today are constantly pumping out press releases hyping their own Six Sigma initiatives. In the right hands, admittedly, it works. But like a lot of management trends, certain aspects of Six Sigma can get downright silly. The management fad gets raves from Jack Welch, but it hasn't boosted the stocks of other devotees. BY LEE CLIFFORD A few years back Whirlpool, the appliance maker that had been reliably pumping out dishwashers and dryers for decades, decided to tackle quality head-on. Executives at the company implemented their own proprietary version of the highly touted principles of Six Sigma, a quality-assurance strategy that has come into vogue in the past several years. Companies like Motorola and General Electric swear by Six Sigma. But as an investor, can you use it as a litmus test of whether a stock is going to appreciate? Probably not. Six Sigma, and a couple of similar-looking knockoffs, are nothing short of a full-on corporate fad, the latest in a long line of must-have efficiency crazes that perpetually spread through corporate America. Fueled in large part by GE CEO Jack Welch-who frequently talks it up to the media-companies today are constantly pumping out press releases hyping their own Six Sigma initiatives. What's more, consultancies have sprung up across the country to help CEOs muster the troops, and the term itself has turned into the financial equivalent of a Good Housekeeping seal of approval. (Incidentally, the name comes from statistics, where the Greek letter sigma is used to measure how far something deviates from perfection. Six Sigma means a company tries to make error-free products 99.9997% of the time-a minuscule 3.4 errors per million opportunities.) In the right hands, admittedly, it works. Welch wrote in GE's 1999 annual report that its initiatives had saved the company more than $2 billion in 1999, just three years after implementing Six Sigma. And there's certainly nothing wrong with a company's trying to improve quality and reduce errors. Whirlpool wanted to make itself more efficient by building its products right the first time rather than spending cash later to fix malfunctioning dryer doors and appease disgruntled consumers. But like a lot of management trends, certain aspects of Six Sigma can get downright silly. The corporate efficiency experts who implement it are coined "black belts"-martial artists who get deployed to chop, kick, and block until errors are virtually nonexistent. Raves Mikel Harry, one of the founders of Six Sigma at Motorola in the 1980s and now head of the Six Sigma Academy, a consulting firm that helps companies train their warriors: "A black belt can save $300,000 to $400,000 per project and return that to the company, and they can do four to six projects a year. On the conservative side, they can save the company $1 million to $1.5 million per black belt!" So what happened at Whirlpool? Though a company spokesman says the program has resulted in "substantial" efficiency gains, analysts aren't quite as impressed. "You'd have to get out an electron microscope" to see any real impact, says Nicholas Heymann, an analyst who follows the company for Prudential. And incidentally, the stock is down 12% over the past two years. So much for the martial arts. "It can be wildly successful," says David Fitzpatrick, the worldwide leader of Deloitte Consulting's Lean Enterprise Practice, "but I would say fewer than 10% of companies are doing it to the point where it's going to significantly affect the balance sheet and the share price in any meaningful period of time." Why? First are the obvious pitfalls: a CEO who isn't really committed, an inability to motivate employees, or a company that allows its initiative to trail off before there's been any progress. But beyond that, Six Sigma can be mindnumbingly vague. If you're manufacturing pills, defects are easy to track, but what about at a customer service center? Exactly what constitutes an "error" or "mistake"? You guessed it-it depends on which black belt is counting. Then there's the latecomer issue raised by some analysts. "Six Sigma's ability to incrementally improve performance and shareholder value is highly correlated to how early a company has implemented it," says Heymann. Bob Hendricks, the CEO of international consulting concern Holt Value Associates, also ventures that the competition is a factor: "If Whirlpool implements it, and then Maytag does too, who wins? The consumers-those savings will mostly get passed along to them." But the main reason Six Sigma is no guarantee of stock market success is also the most obvious one: Defects don't matter much if you're making a product no one wants to buy. As one consultant notes, referring to Motorola's disastrous foray into satellite-linked mobile phones: "Remember, Iridium came out of a company that's famous for Six Sigma." So while dozens of companies may be saving money with these error-reduction programs, a lot of others are spending valuable time and resources for something that may never have any tangible payoff for shareholders. Even the concept's biggest booster can't argue with that. Says Mikel Harry: "I could genetically engineer a Six Sigma goat, but if a rodeo is the marketplace, people are still going to buy a Four Sigma horse."