An Investigation of the Average Bid Mechanism for

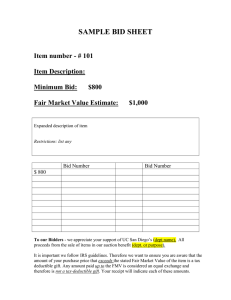

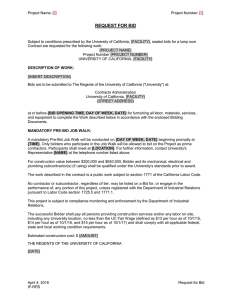

advertisement