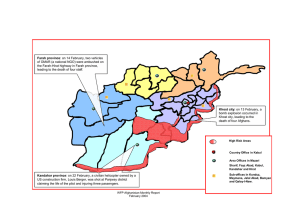

Khost Province District Studies

advertisement