Does The ADA Protect The Violent Employee?

advertisement

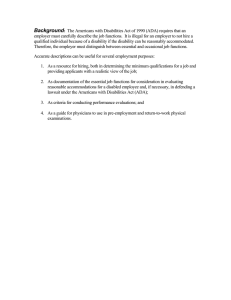

Does The ADA Protect The Violent Employee? By Barbara E. Hoey* This article is republished with permission from the August 2003 edition of The Metropolitan Corporate Counsel. Just this past month, the news was again filled with a tragic story of an employee who – in a burst of violence – killed several co-workers and himself. Such incidents are, unfortunately, not uncommon. However, and without commenting specifically on the employee or company involved in the most recent incident, many of these incidents are predictable and could be prevented. The incidents are predictable in that in the vast majority of cases you will find that the employee in question had some history of violent or aberrant behavior. The employee may have previously threatened others in the workplace, or actually committed prior acts of violence in the workplace. The questions presented are – must an employer “tolerate” or “accommodate” such a violent employee? Can an employer, after an incident of a specific threat or act of violence, terminate the employee? Is a single act of violence enough to justify an employee’s discharge? These situations become particularly challenging if the employee has a diagnosed mental illness. Dealing with a mentally-ill employee who is accused of this type of behavior is the functional equivalent of walking a “legal tightrope.” Many factors must be considered in determining the appropriate discipline for any given incident – such as prior history, years of service, obligations, union contracts and, of course, the law. However, if the “violent” employee is diagnosed with a mental illness, he/ she may also be protected by the federal Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”), as well as state discrimination statutes. Hence, the employer who disciplines or discharges such an employee may well find itself in court, accused of disability discrimination. The employer thus must balance the rights of the disabled employee and its legal obligations to the rest of the workforce. To achieve the correct balance, an employee must have a basic working understanding of the ADA. In a nutshell, the ADA prohibits employment discrimination against employees who have physical or mental disabilities, but are “otherwise qualified” to perform the essential functions of their jobs with or without reasonable accommodation.1 * Barbara E. Hoey is a Partner at Kelley Drye & Warren LLP. 1 See 42 U.S.C.A. §§12111(8) and 12112(a). First, not all mental conditions or illnesses constitute “mental disabilities” under the ADA. The ADA defines a mental disability as a “mental impairment” that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities” of the individual2. It is not difficult for an employee to establish that his or her condition constitutes a mental impairment under the ADA. Courts generally accept as proof of mental impairment a diagnosis of a mental disorder from a licensed health care professional. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (often referred to as the “DSM-IV”) is the standard reference for mental diagnoses. Once the employee establishes that he/she has a “mental impairment,” he must also prove that the mental impairment substantially limits one or more of his major life activities. The determination of whether an employee is substantially limited in the performance of one or more of his major life activities must be made on an individualized, case-by-case basis. In Toyota Motor Mfg., Kentucky, Inc. v. Williams, 534 U.S. 184, 198,122 S.Ct. 681, 692,151 L.Ed.2d 615, (2002), the Supreme Court held: “The determination … is not necessarily based on the name or diagnosis of the impairment the person has, but rather on the effect of that impairment on the life of the individual.” (internal quotation marks omitted.) According to EEOC regulations, “major life activities” include “functions such as caring for oneself, performing manual tasks, walking, seeing, hearing, speaking, breathing, learning, and working.”3 This EEOC list of basic functions was not intended to be exhaustive and courts have expanded it over the years. For instance, the ability to sleep, eat and have sexual relations have been held to be “major life activities.” 4 Other courts have held that the ability to interact or “get along with others” may be a major life activity.5 The Second Circuit was recently presented with this issue, in a case where a supervisor with a history of psychiatric problems was fired after an incident of verbal abuse toward a subordinate, which triggered an investigation that revealed other instances of abusive conduct toward employees. Cameron v. Community Aid for Retarded Children, 2003 U.S. App. LEXIS 13605 (2d Cir. 2003). The subordinate resigned. The supervisor subsequently requested the employer “accommodate” her disability, by barring that subordinate from the premises altogether. In affirming summary judgment for the employer, the Second Circuit recognized that the case raised the question of “whether an inability to interact with others is a disability within the meaning of the ADA.” It decided however, that it did not have to rule on that issue. For one, plaintiff denied her “disability” interfered with her performance. The court also held that the plaintiff, because of her conduct and her inability to interact with her subordinate and other 2 3 4 5 42 U.S.C.A. § 12012(A). 29 C.F.R. §1630.2(i). See, for example, McAlindin v. County of San Diego, 192 F.3d 1226,1234 (9th Cir. 1999), holding that sexual relations, sleeping and interacting with others were major life activities under the ADA; Soileau v. Guilford of Maine, 105 F.3d 12 (1st Cir. 1992) (holding that inability to get along with others was not a “disability” which an employer should be required to accommodate). However, in Jacques v. DiMarzio, Inc., 200 F.Supp.2d 151, 160 (E.D.N.Y. Feb. 27, 2002), a New York District court held that such a function was as basic as walking and breathing and did constitute a major life activity. employees, was “unqualified to be a supervisor.” It further held that plaintiff’s “conclusory denials” as to the truth of the complaints about her behavior were not sufficient to defeat summary judgment. Hence, this issue still remains an open one in this Circuit. Moving to the next “prong” of the ADA analysis (assuming the employee can establish that he is “disabled”), the employee must then prove that he is a “qualified individual”, i.e. able to perform the essential functions of his job, with or without reasonable accommodation.6 Notably, no circuit court has ever found a violent or potentially violent employee to be a “qualified individual” under the ADA, even where the employee is able to establish that he was violent because of the nature of his mental disability. Here, one must begin with the basic proposition recognized in many ADA litigations – that a “disabled” employee may lawfully be disciplined for misconduct for which a “non-disabled” employee would likewise be disciplined. See e.g. Bates v. Long Island Railroad, 97 F.2d 1028 (2d Cir.) cert denied 510 U.S. 992 (1993). Hence, if you can show that you would fire a nondisabled worker for threatening or injury to another worker, you should generally be able to apply that same standard to the “disabled” employee. The disability should not shield the disabled worker from discipline. Two recent court decisions serve to illustrate this point. In Koshko v. General Elec. Co., 2003 WL 1582285 (N.D.Ill. Mar. 26, 2003), an employee was fired after an incident where he returned from a meeting cursing and threatening to kill his manager. In addition, the employee punched the air with his fists and blooded his own hand by slamming it down on his tabletop. In his suit under the ADA, he alleged that General Electric had denied him a reasonable accommodation by discharging him because of his mental disability. General Electric moved for summary judgment, arguing that even if Mr. Koshko was disabled within the meaning of the ADA, he was not a “qualified individual” because he was prone to violent outbursts in the workplace and thus posed a “direct threat” to the health and safety of others.7 The District Court agreed with General Electric and dismissed the case on the ground that Mr. Koshko’s violent outburst rendered him unqualified for his position, pointing out: “(T)he Seventh Circuit plainly has held that an employer does not have a duty to accommodate an employee’s alleged disability when that disability creates or results in violence in the workplace.”8 Citing Palmer v. Circuit Court of Cook County, 117 F.3d 351, 352-353 (7th Cir. 1997), the District Court reasoned that to hold otherwise would “place the employer on a razor’s edge – in jeopardy of violating the Act if it fired such an employee, yet in jeopardy of being deemed negligent if it retained him and he hurt someone.” 6 7 8 See 42 U.S.C.A. §12111(8). See 42 U.S.C.A. §§12111(3) and 12113(b) regarding the “direct threat” defense available to employers. In Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Echazabal, 536 U.S. 73, 122 S.Ct. 2045, 153 L.Ed.2d 82 (2002), the Supreme Court ruled that the EEOC was authorized to expand the ADA statutory definition of “direct threat” to include an individual who posed a direct health or safety threat to himself. See 29 C.F.R. §1630.15(b)(2). Koshko v. General Elec. Co., 2003 WL 1582285, *4 (N.D.Ill. Mar. 26, 2003). The First Circuit also recently held that an employee who was prone to violence was not a “qualified individual” under the ADA. In Calef v. Gillette Company, 322 F.3d 75 (1st Cir. 2003), a former employee alleged that Gillette had discriminatorily denied him a reasonable accommodation, harassed him, and subsequently discharged him because of his mental disability. The district court granted summary judgment for Gillette, which the First Circuit affirmed on appeal. This case is particularly instructive for employers. The Court relied heavily on Gillette’s employment policy prohibiting misconduct in the workplace and its uniform application of this policy to all employee offenders. Gillette’s supervisors who witnessed Mr. Calef’s violent and threatening acts contemporaneously prepared memoranda or written warnings detailing what had occurred. Thus, Gillette had a “paper trail” to justify its discharge of Mr. Calef. Although Gillette subjected Mr. Calef to progressive discipline for each of the six incidents of misconduct that had occurred, the Court implicitly noted that even one act of violence or threatened violence will suffice to discharge that employee for the security and safety of others. The Court also gave significant weight to the reasonable (objective) and genuine (subjective) fear engendered in those Gillette employees who witnessed or were subjected to Mr. Calef’s threatening behavior. Ultimately, the Court held that Mr. Calef was not a “qualified individual” under the ADA, based on his threatening behavior toward other employees in the workplace. What Should The Prudent Employer Do? First, be proactive – make sure you have a clearly-publicized policy and enforce that policy in a uniform fashion. Train your managers and Human Resources staff to recognize and properly report incidents of violence and threatened violence. It is far more difficult for a disciplined or discharged employee to claim disability discrimination for having committed or having threatened to commit violent acts when an employer has a code of conduct or a zero-tolerance policy regarding violence in the workplace that is uniformly applied to all employees. Second, engage in prudent measures to prevent litigation. Once a situation is reported, the employee should be immediately removed from the workplace (possibly suspended with pay) and a thorough investigation conducted. If the employee has a diagnosed mental condition, consult a psychiatrist and get some professional assessment of the situation. One consideration may be whether medication could alter the behavior. It is clear from the case law that the ADA does not require employers to “accommodate” or protect violent employees or those employees prone to violence. The ADA was designed to protect the victim, not the victimizer of workplace violence. Employers who employ individuals who are violent or threaten violence risk having to defend against negligent hiring, negligent retention or supervision claims commenced by those employees9 or third parties (guests, customers, independent contractors, etc.) who are injured at the workplace as a result thereof.10 However, a word of caution: employers who without a thorough investigation, summarily 9 10 Under certain circumstances, employees may bring direct suit against their employers for injuries sustained in the workplace, regardless of exclusivity provisions contained in state workers’ compensation laws. New York Labor Law §200 explicitly requires employers to provide “reasonable and adequate protection” to the “lives, health and safety” of employees and others at the workplace. N.Y. Lab. § 200(1) (2002). discipline or discharge employees falsely or maliciously accused of violence or violent outbursts in the workplace do so at their own risk. Clearly, employers must be fair and thorough when investigating charges of employee misconduct, including accusations regarding violence, to avoid defamation, wrongful discharge and other related claims.