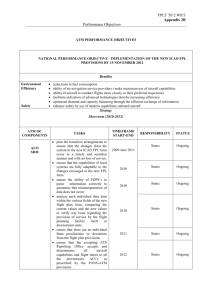

AGC European Action Plan for Air Ground

advertisement