Nickel Silver - Society for Historical Archaeology

advertisement

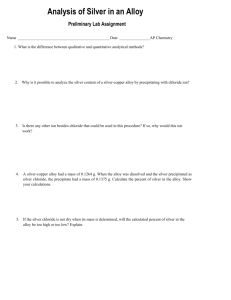

the alloy, with discoloration occumng when the nickel content ranges below 25% (Vickers 1923: 458-60). Surface whitening of lower grade alloys of this type was accomplished by Nickel Silver: An Aspect of early manufacturers through the use of sulMaterial Culture Change in the furic acid baths. Although the dominant metallic constituents used in the production of Upper Great Lakes Indian Trade nickel silver consist largely of copper, nickel, and zinc, other metals were often included ABSTRACT (Table I), depending on the purpose to which the alloy was to be employed. The industrial expansion of Western society during the Besides lead and iron, a wide range of eleearly 19th century fostered extensive modifications within both the organizational and material aspects of ments occumng as impurities in the alloy were Euroamerican culture and that of other technologi- also present, a fact which rendered quality cally dependent groups. This paper addresses itself to a control over the early productions of the single facet of this problem as illustrated through the nickel silver industry virtually impossible introduction and subsequent adaptive utilization of (Adams 1960: 104). The better grades of alloy German or nickel silver as a precious metal substitute produced during the 1830s were reported as in the Great Lakes Indian trade during the second quarter of the century. While the decline of profit gains being indistinguishable from silver except “by gleaned from the fur industry may have played a part in fracture” (Holland 1836:49). This situation this transition, other economic and cultural factors would obviously be critical in an archaeologiappear far more critical in understanding the motivacal context where the two might be easily contions behind this selective process. fused. While such techniques as X-ray fluorescence analysis might be used in identificaDevelopment of Nickel Silver tion, simpler tests can also be performed. Although nickel silver and silver appear simi- Since nickel silver is a metallurgically defined lar in visual examination, certain observable alloy containing no silver, a determination as traits are occasionally present which generally to the presence or absence of this metal allow for their segregation. When subjected to through chemical analysis would be a prelimiintensive polishing, for instance, some nickel nary step in identifying the alloy. This can be silver specimens exhibit a coppery-red or accomplished by immersing a specimen yellowish tinge. The intensity of this effect is sample from the artifact in question in a 50% dependent upon the compositional qualities of solution of nitric acid (HNO,) and distilled C. STEPHAN DEMETER TABLE 1 RECOMMENDEDNICKEL SILVER COMPOSITIONS Knives and Forks Snuffers and Trays For Rolling For Soldering Most White, Brittle and Hard ~~ Copper Nickel Zinc Lead Iron 50 25 25 00 00 -100 (Holland 1836:4J3) 55 22 23 00 00 -100 60 20 20 00 00 -100 57 20 20 3 00 53 22 23 00 2 -100 -100 AN ASPECT OF MATERIAL CULTURE CHANGE IN THE UPPER GREAT LAKES INDIAN TRADE water. The addition of ammonium chloride (NH,CL) to the medium will produce a white precipitate, silver chloride, if silver is present. Documentary evidence relative to the development and subsequent spread of the nickel silver industry in Europe remains relatively obscure. According to one source, the alloy was first developed and commercially manufactured at Hildburghausen, Germany, during the early 19th century. Its general use, however, was reported as occumng only after 1830 (Alberts 1953: 77). Other investigators have specified an 1825 date for the alloy’s invention and have further identified its introduction into North America trade as dating to the post 1832 period (Douglas and Maniott 1942). The reliability of these statements, as they relate to the alloy’s place and date of invention, are extremely questionable. A contemporary article which appeared in the October 1836 issue of the Journal of the American Zttstitute referred to the alloy as “Packfong” or the “white copper of China,” noting that it had been “used a long time by the Chinese” (Holland 1836: 48). The use of pai-Thung (Le., white copper) in China appears actually to date as early as the 8th century A.D. By the opening of the 17th century, Chinese technological works such as the Great Pharmacopoeia (Pen Tshao Kang Mu) by Li Shih-Chen and the Exploitation of the Works of Nature (Thien Kung Khai Wu) by Sung Ying-Hsing reported the alloy as being composed of copper, zinc oxide (lu Kan Shih), and another element identified as phishih. This latter term normally refers to arsenious acid and has been interpreted in this context as being niccolite, an arsenide of nickel (NiAs), found in cobalt (Howard-White 1963: 14). Nickel was never identified as an element in Oriental science and was only distinguished in the West in 1751. During the mid-18th century articles of nickel silver made up at least a small portion of the Chinese-European trade. Triangularly shaped bar ingots of this alloy were at that time being shipped from Yunnan to Canton 109 where artisans cast them into numerous forms such as basins, ladels, mugs, and other articles acceptable to European taste. Throughout this period, most Europeans believed pai-Thung to be a metal rather than an alloy, and as late as 1775 one enterprising Englishman went so far as to smuggle a supposedly unprocessed nugget of the ore out of China (Howard-White 1%3: 42-3). Metallurgical analysis conducted the following year by the Swedish Chemist Gustav von Engstrom indicated the alloy composition of pai-Thung as being copper (40.6), nickel (18.75), and zinc (31.25). Although the remaining 9.4% of the alloy composition was not specified, it probably consisted largely of iron. Such proved to be the case when further tests were conducted by A. Fyfe, in 1822, revealing a composition of copper (40.4),nickel (31.6), zinc (25.4), and iron (2.6) (Howard-White 1%3: 44; Holland 1836: 48). During the same period that Engstrom was conducting his examinations, a white copper alloy was reportedly being manufactured in the Shul mining district of Saxony. As with its Chinese counterpart, the German product, known as Luhler white copper, consisted of copper (88), nickel (8.7), iron (1.7), and sulphur (.6) (Adams 1960:104). Both alloys lacked ductility, were brittle, and easily broken. All were reportedly of cast manufacture. The production of this alloy was relatively small and almost totally restricted to the manufacture of items such as spurs and gun mountings (Vickers 1923: 456). As a marketable item nickel silver was apparently of only marginal importance in Europe until the second decade of the 19th century. At that time significant cost differentials began to emerge in the relative values of gold and silver as a result of decreased silver production in Latin America during the revolutionary period. According to British Consular Records, the ratio of gold and silver produced in Spanish America between 1790 and 1809 was approximately 1:16.4. During the period from 1810 to 1829 this figure had been 110 reduced to as little as 1:9. When considering the output of recently discovered ore deposits in both the United States and Asiatic Russia, the ratio of gold to silver production by the 1820s was estimated as being set on a scale of about 1:7 (M’Culloch 1854: 34445). While other reserves of silver were available, such as stored bullion, coin, and plate, the market price demanded for the metal witnessed a material rise. In 1821 the London price for 437.5 grains, or one ounce, of standard silver averaged 4 s Ild or about $1.411 (Cayley 1830: 117). By 1836 the price had increased to approximately 6 s Ild ($1.90) per ounce, and in 1853, rose even further to 7 s Id ($2.04) per ounce (Farmer 1886: 15). Substantial increases in the market price of silver also occurred in North America. In 1849 an ounce of standard silver was evaluated at about $2.00, while gold was figured at $16.00 per ounce. This essentially created a market ratio of 1:8 operating in opposition to the federally legislated standard, adopted in 1834, of 1 :16.002 (Comstock 1849: 154). Needless to say this disparity led to serious problems in the nation’s monetary system. The silver dollar, for example, had by 1837 increased in its European market value to approximately $1.03, a fact which tended to drive silver coinage out of circulation. (Bakewell 1936:32). The resulting scarcity of specie, especially in the frontier settlements, had the effect of further inflating the value of currency. During the early 184Os, specie in the Saginaw region of Michigan was reported to be circulating at a rate of more than 30%above face value. Thus, the premium placed on a dollar meant that its purchasing power in actual goods or services IThe rate of exchange employed in this study is based on data provided by Farmer for silver prices during the 18331844 period; Id being estimated at about $.024, IS at $.288 and4Sat$l.l52(Farmer 1886: 15-6). Theactualexchange rates employed by merchants in Detroit in 1855 placed a much higher premium on United States currency quite possibly because of its greater silver content. At that time $.02 was estimated as being equivalent to Id, $.25 at 1s Id, and $1 .OO at 4 s 4d(Johnson 1855: 249). HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, VOL.UME 14 was equal to at least $1.30 (Dumond 1%6:705). It was not until 1853 that Congress reduced the silver content of United States coins, thus raising the face value beyond the bullion content and rendering their export to the European silver market as unprofitable. This measure was only enacted after the production of gold from the newly discovered ore deposits of California and Australia had further reduced the ratio of gold to silver output to about 1:4 (Mulhall 1880532). By 1859 the value of an ounce of silver accordingly increased to 7 s 8d or about $2.2 1 on the London Exchange (Farmer 1886: 16). The continued rise in the value of silver throughout this period opened a ready market to nickel silver manufacturers. In 1824 two factories producing the alloy were operating in the Schneeburg district of Saxony. Under the product names of “Argentan” and “Alpakka” a variety of cast manufactured wares such as forks, spoons, and other household goods began to appear in Central Europe. By 1830 consignments of arsenical ores from Saxony were being shipped to two London firms, Johnson, Matthey and Company and F. and S. R. Topping, which were then engaged in the manufacture of the alloy (Howard-White 1963:45-7). The expansion of the nickel silver industry in Europe, as noted by Alberts (1953), was largely restricted to the post-1830 period. The exportation of nickel silver articles to the North American market probably dates no earlier than sometime shortly after the development of the English industry. However, both the quantity and variety of goods entering the United States during this early period was undoubtedly limited, as suggested through such source materials as contemporary newspaper accounts. An article which appeared in the Detroit Journal and Michigan Advertiser illustrates the fact that as late as 1834 the alloy was still a relatively unknown material which the newspaper’s editor predicted might someday usurp the position of silver as a precious metal. AN ASPECT OF MATERIAL CULTURE CHANGE IN THE UPPER GREAT LAKES INDIAN TRADE 111 alloy from which their articles were produced. The use of imported ingots, as produced by Johnson, Matthey and Company, or the sheet metal of Askin and Merry is far more probable. The use of the designation “American Silver Composition,” however, may be suggestive of a domestic source. This application By 1837 the expense of German silver goods was in fact coined by a “foreigner,” Dr. had dropped to one fourth the price of their Lewis Feuchtwanger, who was apparently silver counterparts, a fact which reportedly producing articles of this alloy as early as led many to exchange their household silver- 1834. Items of Feuchtwanger’s manufacture ware for articles composed of this cheaper al- included spoons, forks, knives, mugs, and loy composition (American Institute 1837: other tablewares which were presumably 502). This decline in cost probably reflects a executed by casting (Adams 1960: 102-03). combination of factors such as the greater The initial production of a ductile nickel silver availability of nickel silver as a result of home alloy in North America can probably be attrimanufacture and increases in the market value buted to Robert Wallace. In 1836 after having purchased a formula for the alloy during a visit of silver. In addition certain technological innova- to New York City, Wallace began producing tions had by 1833 allowed for the production nickel silver sheeting out of a rolling mill in of the alloy in sheet form. This article, first Waterbury, Connecticut (Lathrop 1926:36). Although exact information relative to the manufactured by the Birmingham, England, firm of Askin and Merry, had the effect of development and output of the American ingreatly expanding the uses to which the alloy dustry is sketchy, certain inferential evidence could be put, thereby also increasing its mar- is reflected through federal tariff legislation. ketability on virtually a world-wide basis The fact that nickel silver was not included among those articles subjected to customs du(Howard-White 1%3 :69-7 1). The North America industry was also initi- ties in the 1833 tariff may be considered a good ated during this period and was originally indicator of its relative unimportance as an centered in the New York City area. The item of domestic manufacture. However, in “several manufacturers” operating in that the subsequent acts of 1842 and 1846, a 30% vicinity in 1836 were described by one ob- levy was imposed upon all foreign manufacserver as being “mostly foreigners and tured articles of this alloy entering the country mountebanks” (Holland 1836:49). Their pro- (Jones 1851:9). By 1846 a Connecticut firm, the Cowles ducts not only included a full range of tablewares but also other articles such as “folding Manufacturing Company, operating out of door rollers, bellpulls, ventilators for hot air, Tariffville, had commenced the production of railings, grates, and fenders” (American Insti- silverplated nickel silver cutlery. The followtute 1837502). By 1838 one manufacturer, ing year the Roger’s Brothers Company of William Chandless, advertised a range of Hartford also began production. Their wares tablewares of specific designs which he was consisted of nickel silver spoons and forks prepared to produce after having made an ini- which the firm was apparently “importing” tial investment of $800.00 for “dies, stamps, from European sources (May 1947:18, 27). presses, rollers, etc. “(American Institute Silver and the Great Lakes Indian Trade 1838:160). It is highly unlikely that any of these early The use of Euroamencan manufactured silmanufacturers was actually producing the raw GERMAN SILVER-The Star says that utensils of this newly invented metal “look as well and last full as long as silver,” at one third the cost. We have no doubt of the value of German, but if it is in the two qualities of appearance and durability as good as silver, then farewell to the value of silver, that value rests wholly upon its value in the useful arts (Advertiser 1834:2). 112 ver ornaments in the Great Lakes Indian trade was recognized by Quimby as among the single most important elements distinguishing the Late Historic Contact period (Quimby 1966:91). This phase is temporally fvted within a 1760 to 1820 date range; the former date representing the collapse of the French regime in North America and the latter being the approximate point when the fur trade ceased being a viable factor in the further economic development of the Great Lakes region. During this period the tribal group existed as a semiautonomous political entity with its members forming a critical link in the procurement of the region’s fur resources. The expansion of the fur trade during the midcentury fostered the development of a complex set of socioeconomic relationships between the Euroamencan and Indian communities. This situation was further complicated as the newly established American Republic began to compete with the British for political and economic control over the region. The influx of goods, many of which were designed specifically for this trade, had a dramatic effect upon native society, especially in the realm of material culture. By at least 1780 the inventory of native manufactures had been almost totally substituted by articles of European origin, creating what Quimby was to refer to as a “Pan-Indian” material culture (Quimby 1966: 140). At about the same time the use of European manufactured silver ornaments began to reach massive proportions (Quimby 1937:71; Barbeau 1942:lO). As a medium of trade, ornaments of this type continued to remain a significant element in the commerce conducted between the Great Lakes Indian and European trader for the next 50 years. While having arbitrarily designated 1820 as the termination date for the Late Historic period, Quimby had earlier postulated the continued occurrence of trade silver ornaments in a temporal context extending through at least the succeeding decade (Quimby 1937:71). The period, from about 1820 to 1840, wit- HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, VOLUME 14 nessed a rapid decline of the fur trade as an important factor in the regional economy of the Upper Great Lakes and also a marked transition in the relationships which the trade had previously fostered between the Indian and European. The collapse of the fur trade, combined with the destruction of the semiautonomous position of the tribe at the close of the War of 1812 and the implementation of the Indian Removal Policy, effectively opened the region to white settlement. While the forced removal of Indian peoples from areas of intensive Euroamencan settlement such as in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois was effectively carried out, the impact of this policy in such states as Michigan and Wisconsin was blunted by the fact that much of the land occupied by these groups, especially in the more northerly areas, was generally unsuitable for intensive agricultural development. Those who remained were either resettled on reservations or continued to occupy unorganized parcels of land within tracts which had been relinquished through treaty. The economic base of these communities tended to become more diffuse in its relationship to the white trader. While hunting and fur trapping still constituted important economic activities, other items such as fish and maple sugar were rapidly growing in demand at the expanding white settlements to the south. As early as 1826 Thomas L. McKenny noted that the latter two foodstuffs formed a significant portion of the trade conducted in the Sault Ste. Marie area with Whitefish being “sold as low as two and three cents a piece” and sugar at “about ten cents per pound” (McKenny 1972: 160). Similarly, the Chippewa of the Saginaw Bay area were reported to have been conducting an active fishing trade with the white settlers entering that region during the early 1840s. One recent arrival noted during this period that he could buy enough fish from the Indians for 25 cents to provide his family of nine with a full meal (Dumond 1966:257). Besides supplying the white community AN ASPECT OF MATERIAL CULTURE CHANGE IN THE UPPER GREAT LAKES INDIAN TRADE 113 with a variety of locally procured food sources, the trade in Indian handicrafts had by the late 1830s developed into a rapidly expanding commercial venture. As noted in two advertisements placed by the Detroit furrier and hat manufacturer, I. C. Stephens, the sale of these articles was to a large extent directed towards the region’s growing tourist traffic: The lack of any mention of silver ornaments or similar gewgaws as being available through this supplier may be signifcant. But whether this should be construed as representing the elimination of such items from the trade is doubtful. As indicated in another advertisement which appeared later that year, the distribution of such goods to traders may well have 500 pairs Indian Moccasins, just received from Macki- been controlled by other elements of Detroit’s naw, 500 pairs of ladies and Misses Bead Moccasins for mercantile community. sale at the Michgan Hat, Cap and Fur Store, 171 Jefferson Avenue I. C. Stephens INDIAN WORK-Just received from Mackinaw, a large and beautiful assortment of Indian Work, consisting of the following articles: Fruit Dishes, Trays, Work Boxes, Baskets, Recticules, Needle Boxes, Pin Cushions, Mococks, Moccasins, and a variety of other articles. Travellers desirous to obtain presents for their friends, cannot find a neater article than the above. For sale at the Michigan Hat, Cap and Fur Store, 171 Jefferson Avenue (Advertiser 183934) The trade with the Indian during the 1830s shifted from the more or less specialized domain of the fur trader to that of the general merchant and country pedlar. While certain articles diagnostic of the earlier phases of the Late Historic period were eliminated, substitutes became available. As late as the 184Os, the enterprising backwoods merchant had a range of especially sorted “Indian Goods’’ available to him through the forwarding houses at Detroit. INDIAN GOODS & BROTHERS JUST RECEIVED-RANDOLPH have, by recent arrivals, received a full assortment of Indian Goods, consisting in part of: 550 pairs 3, 2-95, 2 and 1% point blankets, 90 do. Save List Clothes 40 do. Broad Clothes-ako, Shawls, Beads Mirrors, Vermillion, Cartouch and Scalping Knives Garterings, Rings, Wampum, Worsted Syams, Levantime Hdk’s, Gun-Flints, Pipes, Etc. Etc.-which together with a full assortment of desirable DRY GOODS are offered at wholesale. exclusively. RANDOLPH & BROTHERS Jefferson Avenue, Detroit (Advertiser 1845a:2) SILVER SPOONS-An assortment on hand and manufactured to order; silver Ear Bobs, Broaches and bands, for the Indian trade. GEO. DOTY 162 Jefferson Avenue (Advertiser 1845b34) The evidence presently available indicates that Doty was not a trained silversmith but rather advertised articles which were either produced by those in his employ or purchased from other manufacturers (Simons 1%9:89). His business operation was not restricted to silversmithing but seems to have been directed more towards that of a wholesale distributor of goods suitable for the pedlar trade. As a facet of this commerce, the use of “silver” ornaments obviously constituted a continuing element in the Indian trade of the Upper Great Lakes at least as late as the mid1840s. The declining use of ornaments of this type beginning in the 1820s was due only in part to the decline of the fur industry. Probably of far greater significance, as has already been noted, was the meteoric rise in the price of silver during this period. As early as 1810, Joseph Varnum, the factor of the United States post at Mackinac, noted that the price of government contracted silver trinkets was so high “. . . that the natives even laugh when the price is mentioned.” Ear bobs sold at the post were received by the government at a cost of $.40 per pair. When the cost of transport and operating expenses were calculated, the retail sale price amounted to $67 per pair, a figure which Varnum reported as being “ . . . far beyond anything heretofore given 114 for silver trinkets only weighting 6% cents . . . ” (Carter 1942:331). By 1820 the price charged for a pair of ear bobs manufactured by Chauncey S. Payne, a Detroit silversmith, was approximately $1.09. The cost of other articles ranged from $06 for a small broach to $8.73 per pair for arm bands: ear wheels brought about $1.49, gorgets about $1.79, and large broaches approximately $1.99 (Dain 1956:150). While these items undoubtedly served to some degree as a means of wealth display in native society, contemporary writers indicate that they were largely viewed only as ornaments (Carter 1942:331; Morgan 190150). To the traders operating among the Great Lakes tribes during this period, the rising cost of silver goods would have created a serious impediment to the success of their operations. The options available to maintain a viable profit margin would have necessitated either the elimination of silver as a regular stock item or the implementation of a general markup in the sale price of such articles. Both procedures would have had the obvious effect of drastically reducing the amount of silver being traded, a situation which is indicated archeologically and which has been established as an attribute marking the close of the Late Historic period. Among other options that would have been open was the substitution of high quality silver goods with either base silver alloys, plated goods, or other nonprecious metals. The former possibility, the use of base silver alloys, was a constant element of the Indian trade as is indicated in a letter from Peter Waraxall to Sir William Johnson dated 27 July 1756: I find the Gorgets with the Kings Arms and your Cyper made of good silver and to do service will come higher than 26s apiece. The Silver Smith here (New York) says those at Albany if made for that price must be very base Metal (Sullivan 1922523). Information gained from the analysis of two silver arm bands associated with a burial (20WN51) excavated in a housing development in the Detroit suburb of Melvindale indi- HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, VOLUME 14 cated an alloy composition of 85% silver and 15% copper (Pilling 1958). The author has been unable to establish whether such a high silver content was common in the manufacture of Indian trinkets. It is, however, worth noting that the ratio of silver to copper occurring in these two specimens is close to the 90% silver composition of coins minted in the United States during the first half of the 19th century. The bulk of the silverworks produced by smiths, especially those operating out of the frontier communities, consisted of circulating specie which was itself a fairly uncommon commodity and often had to be imported (Barbeau 1942:ll). In 1821 the use of cut money in lieu of small circulating change was outlawed as a medium of payment in Detroit because of the practice of clipping which reduced the size of each of the eight bits to less than their value of about 12W. The pieces were reportedly removed from circulation, . . . sold by the ounce, and used for the manufacture of silver ornaments for the Indians” (Trowbridge 1877:382).The ornaments marketed by Chauncey S. Payne in Detroit during the early 1820s were probably manufactured from coin silver and commanded a premium price unlike the silver trinkets which the American Fur Company was distributing at about the same period. The small broaches Payne produced sold at about 6$ apiece; those which the American Fur Company handled went for $2.57 per hundred, or a little over 2M$ apiece (Alberts 195352). While the latter would surely have possessed an advantage in dealing with mass quantities of goods, this could hardly be enough to explain the rather significant cost differential which existed between the two articles, especially if one further considers the fact that Payne’s price included only the manufacturer’s markup and did not include the cost of transport and operating expenses which the distributor faced. It is more likely that the silver content of the items handled by the fur company was far below the standard of coin. A measure which would have greatly reduced their intrinsical “ AN ASPECT OF MATERIAL CULTURE CHANGE IN THE UPPER GREAT LAKES INDIAN TRADE value but also greatly increased their marketability as a cheap temporary ornament. The archaeological literature dealing with the presence of nickel silver trade ornaments stylistically attributable to the Late Historic period in the Great Lakes region is extremely scarce. It was not until the analysis of the Matthews’ site (2OCL61) material that any substantive information dealing with the occurrence of this alloy became available. This site was initially discovered and excavated by the late Clyde B. Anderson, an amateur archaeologist, in 1966 and subsequently reported upon six years later by Charles E. Cleland of Michigan State University. Its location was adjatent to the Maple River on the boundary line dividing Gratiot and Clinton counties in Central Michigan. A description of the flat metal trade ornaments recovered from the site was presented in Cleland’s report (1972) and will not be dealt with in any detail in the present analysis. The four burials from which these specimens were collected have been identified as being of probable Chippewa ethnic affiliation; they consisted of two adult males, an adult female, and a probable adolescent female. The articles recovered with the two male interments (Burials 1 and 2) consisted of silver, silver plated, and nickel silver ornaments, with the latter alloy reportedly comprising the bulk of 115 the collected sample (Table 2). Of the silver objects, three gorgets, all were associated with Burial 2. Two of the specimens measured 125.5 mm in diameter with one bearing the mark of Robert Cruickshank, a Montreal silversmith active from about 1774 to 1809. The other gorget, measuring 114 mm, bears the touchmarks of “BP” and “PJD” attributable to the firm of Jean Baptiste Piquette and Pierre Jean Desnoyers, which operated out of Detroit from 1803 until 1805 (Simons 1%9:702). The silver plated ornaments associated with the male burials included two fragmentary broaches decorated with a series of elaborated geometric perforations and two circular gorgets. These specimens were recovered from Burial 1, measure 166 mm in diameter, and are both marked with the initials “P-H” indicating their manufacture by either Pierre Huguet dit Latour or his son, both of whom operated out of Montreal from approximately 1770 until 1829 (Buhler 1%9:Fig. 23). The remainder of the male associated ornaments consisted of nickel silver alloy articles. Those with Burial 1 included a large broach (80 mm) decorated with a single row of elongated oval perforations along the outer margin and two inner rows of concave sided diamond shaped perforations, two engraved circular gorgets (143 mm), two engraved arm bands, and an ear wheel (47 mm) decorated with an outer and TABLE 2 DISTRIBUTION OF FLAT METAL ORNAMENTS (2OCL61) Ear Broaches 1 2 3 4 TOTALS Gorgets 3 1 9 0 2 2 2 Wheels 2 1 Ann Bands 2 2 Hair Pipes 2 11 8 90 1 1 1 91 2 3 4 2 1 4 2 110 116 inner row of circularly shaped punched holes. The nickel silver articles recovered from Burial 2 included two hair pipes, two engraved arm bands, and two engraved circular gorgets measuring about 74 mm in diameter. The items associated with Burial 3, an adult female, consisted of 90 miniature nickel silver broaches which ranged in size from 21 mm (48), 16 mm (40) and 12 mm (2). A single large silver broach (80 mm) was interred with an adolescent in Burial 4. This specimen is described as being virtually identical in design to the similarly sized nickel silver broach associated with Burial 1. On the basis of these and other grave goods associated with the Matthews site burials, Cleland postulated their temporal placement as being approximately 1825- 1830 (Cleland 1972: 186). This date range is at least eight years earlier than the first known production of ductile nickel silver sheeting, a material which would have been essential in the production of the above articles. The relative scarcity of nickel silver in North America as late as 1831 is well illustrated through the fact that the New York Customs House charged one importer a silver duty on a European consignment of the alloy (Adams 1%0:102). The importance of the British industry as an early source of supply of nickel silver to North America is strongly hinted at through the use of the term “English silver” as a designation for the alloy commonly employed in the United States during this period (Holland 1836:49). The use of nickel silver articles in the Great Lakes Indian trade by the late 1830s and early 1840s is demonstrated through a number of advertisements which appeared in Detroit newspapers during that period. One of these placed by a Cleveland based firm during the spring of 1838 was directed to a special range of clientele identified in bold letters as “Pedlars and Indian Traders.” Among the items listed on sale were a broad range of “German Goods” including such articles as spectacles, thimbles, earrings, rings, and breast pins HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, VOLUME 14 (Advertiser 1838:4). A similar advertisement, which appeared several years later in 1846, was placed by George Doty who offered “Pedlars Goods” at his auction room consisting of ‘‘ . . . Dutch Pipes, . . . German silver table . . . (and) . . . tea spoons, German silver pencils, German silver thimbles, German silver spectacles . . . (Free Press 1846a:3). During this same period another Detroit silversmith, Charles Piquette, offered his patrons a stock of “200 Ibs. German silver, in the sheet. . . (Free Press 1845:3). Apparently the venture proved successful as the following year Piquette offered a new supply of the alloy, referring to it as “a first rate article” (Free Press 1846b:3). The bu(k of the nickel silver goods entering the frontier settlements during the 1830s were probably composed almost exclusively of finished products. While certain amounts of bulk metal undoubtedly reached the shops of Western silversmiths, its sale in that form would have been marginal until production had far outdistanced the needs of the silversmiths themselves, a situation which was apparently taking place by the mid- 1840s if not earlier. The more generalized access to the alloy in bulk form should be readily discernible in an archaeological context as reflected in both the variety and quality of goods encountered. The use of nickel silver sheeting as a medium of Indian workmanship has previously been documented by Mooney among the Kiowa during the mid- 19th century (Mooney 1898:3 18-19). ” ” Conclusions This paper has attempted to illustrate at least in part that other factors beyond the collapse of the fur industry played a major role in the elimination of the specialized range of silver ornaments diagnostic of Great Lakes Indian culture throughout the Late Historic period. In this case the spiraling cost of silver during the early 19th century rendered the continued manufacture and trade in these articles commercially impractical. A result of AN ASPECT OF MATERIAL CULTURE CHANGE IN THE UPPER GREAT LAKES INDIAN TRADE this situation, as expressed archaeologically, would be the substitution of silver ornaments by those composed of base metal alloys or silver plate. As the importance of the trade conducted between the Euroamerican and Indian communities continued to decline over the succeeding years, the occurrence of these articles would have been drastically reduced and eventually deleted entirely as a material element of native culture. This appears to have been an ongoing process in some areas for over as much as a 30 year period from about 1820 to 1850. Among the more diagnostic features of this transitional phase was the introduction of nickel silver as a replacement for silver in the manufacture of flat metal ornaments such as broaches, gorgets, arm bands, and a variety of other ornamental forms commonly associated with the Indian trade. The presence of these items in an archaeological context provides a viable medium for relative dating. Nickel silver sheet metal articles which have occasionally been identified in site situations are categorically restricted to the post 1833 period for time of manufacture. Although the production of nickel silver and related alloys used in cast manufacture had begun in Germany by the mid-18th century, its use was limited. As late as 1830 the alloy was rejected by the Shefieid cutlerers because it was found to be too brittle for industrial use (Kimsworth 1953: 116). Because of its crystalline structure, the conversion of the alloy into a sheet form proved impossible until further technological processes were developed. As previously noted this was not accomplished until 1833 when Askin and Merry subjected their cast manufactured plate ingots to certain annealing techniques which served to modify the alloy’s molecular structure and render it suitable for rolling into a ductile sheet form. Its adaption in the manufacture of trinkets utilized in the Great Lakes Indian trade undoubtedly dates to this time, with the initial sources of the alloy being restricted to British 117 and possibly German producers. The subsequent manufacture of the alloy in North America, beginning in about 1836, apparently did not have an appreciable impact on the market for at least the next several years. Information presently available indicates that the commercial manufacture of Indian trade ornaments, presumably of nickel silver alloy, continued until as late as 1845. On the basis of this data, the dating of such sites as the Matthews site, where the bulk of the ornamental goods consisted of nickel silver articles, could be fixed within a temporal range extending from 1833 to approximately 1845 or later. The retention of these articles as an element of material culture in Indian society was probably quite varied between groups and individuals. This was largely a result of the degree of assimilation of group members subjected to a more intensified range of contact situations. During the late 184Os, Morgan noted that among the Iroquois these ornaments were almost totally restricted to female use (Morgan 1901:49), or more appropriately, among that segment of the population which was less prone to enter into contact associations and which consistently remained a bulwark of cultural conservatism. The use of ornaments of this type, largely among females, is known to have continued among some groups up until as late as the turn of the present century. As suggested by a number of investigators, these productions were probably largely the result of native manufacture (Alberts 1953: 72; Morgan 1901: ). While the use of coin silver obtained from circulating specie is well documented among Indian silversmiths of this later period, the extent to which nickel silver may have been employed remains unknown. It may well be worth noting, however, that Indian speciality stores catering to the present generation still offer a range of ornamental goods generaly following traditional forms listed under the catalogue heading of “German Silverworks” (Treaty Oak n.d.: 5; Ozark 1975: 14). HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, VOLUME 14 118 REFERENCES ADAMS, E. H. 1960 Dr. Lewis Feuchtwanger. In Selectionsfrom the Numismatist, 101-106. Whitman Publishing Company, Racine. ADVERTISER, DETROIT DAILY 1838 Cleveland Bazaar. 3 (637): 4. 1839a Indian Work; Michigan Hat, Cap and Fur Store, 5 (76): 3. 1839b SO0 pairs Indian Moccasins; Michigan Hat, Cap and Fur Store. 5 (76): 4. 184Sa Indian Goods; Randolph & Brothers. 10 (276):2. 1845b Silver Spoons; Geo. Doty. 1 1 (90): 4. ADVERTISER, DETROIT JOURNAL A N D MICHIGAN 1834 German Silver. 5 (39): 2. ALBERTS, ROBERT C. 1953 Trade Silver and Indian Silvenvork in the Great Lakes Region. WisconsinArcheologist 34 (1): 2121. AMERICAN INSTITUTE, THE 1837 German Silver, or American Silver Composition. Journal of the American Institute 2(9): 502. 1838 German Silver. Journal of the American Institute 4(3): 160. BAGEHOT, WALTER 1877 Some Articles on the Depreciation of Silver and on Topics Connected With It. H . S. King & Company, London. BAKEWELL. PAUL 1936 Past and Present Facts about Money in the United States. MacMillan Company, New York. BARBEAU, C. MARIUS 1942 Indian Trade Silver. The Beaver: A Magazine of the North. Outfit 273: 10-14. BUHLER. KATHRYN C. 1%9 The Campbell Museum Collection: Silver. The Campbell Museum, Camden, New Jersey. CARTER, CLARENCE E. (EDITOR) 1942 The Territorial Papers of the United States: The Territory of Michigan, 1805-1820. 10:330-32. CAYLEY, E. S. 1830 Commercial Economy. Photo reprint (1971). Irish University Press, Shannon. CLELAND, CHARLES E. 1972 The Matthews Site (2OCL61), Clinton County, Michigan. The Michigan Archeologist 18 (4): 175-207. COMSTOCK, JOHN LEE 1849 A History of Precious Metals. Belknap & Hamersley, Harford, England. DAIN.FLOYD R 1956 Every House a Frontier: Detroit’s Economic Progress, 1815-1825. Wayne State University Press, Detroit. DOUGLAS,F. H. AND ALICEL. MARRIO~T 1942 Metal Jewelry of the Peyote Cult. Denver Art Museum, Material Culture No. 17. DUMOND, DWIGHT L. (ED) I966 Letters of James Gillespie Bimey. 2: 257, 706. Peter Smith, Gloucester. FARMER, E. J. 1886 The Conspiracy Against Silver. Photocopy reprint (1969). Greenwood Press, FREEP R E S S , DEMOCRATIC (DETROIT) 1845 German Silver; C. Piquett. 9(60):3. 1846a Pedlar’s Goods at Doty’s Auction Room. 10 (85): 3. I846b German Silver; C. Piquette. IO (150): 3. HARROD, ROY 1963 The Dollar. W. W. Norton & Company, New York. HERRICK, RUTH 1958 A Report on the Ada Site, Kent County, Michigan. The Michigan Archeologist4( I): 1-27. HOLLAND, HOMER 1836 “White Copper of China.” Journal of the American Institute 2 (1): 4849. HOWARD-WHITE,F. B. 1%3 Nickel, An Historical Review. D. VanNostrand Company, New York. JACOB,WILLIAM 1832 An Historical Inquiry into the Production and Consumption of the Precious Metals. Carey and Lea, Philadelphia. JOHNSON,JAMESDALE(ED) 185.5 The Detroit City Directory and Advertising Gazetteer of Michigan for 1855-1856. R. F. Johnstone and Company, Detroit. JONES,A. 1851 The Revenue Book: Containing the New Tariffof 1844, Together with the Tariffof 1842. Geo. H. Bell, New York. KIMSWORTH, S. B. 1953 The Story of Cutlery from Flint to Stainless Steel. Ernest Benn, Ltd, London. LATHROP, WILLIAM G. 1926 The Brass Industry in the United States. Wilson Lee Company, New Haven. LANGBIEN, GEORGE AND WILLIAM T. BRANNT 1924 Electro-Depositionof Metals. New York: Henry Carey Baird & Company, New York. AN ASPECT OF MATERIAL CULTURE CHANGE IN THE UPPER GREAT LAKES INDIAN TRADE M’CULLOCH, J. R. (ED) 1854 Precious Metals. In A Directory of Commerce and Commercial Naviagation 2:343-8. A. Hart, Philadelphia. MCKENNEY. THOMAS L. 1972 Sketches of a Tour to the Lakes. Imprint Society, Barre, MAY,EARLC. 1947 Century of Silver 1847-1947. Robert M. McBride &Company, New York. MOONEY. JAMES 1898 Calendar History of the Kiowa. Bureau of American Ethnology 17. Smithsonian Institution. MORGAN, LEWISH. 1901 The League of the Ho-de-no-Sau-nee or Iroquois (Vol. 2), edited by H. M. Lloyd. Dodd, Mead, New York. MULHALL, MICHAEL G. 1880 The Progress of the World. Photo reprint (1971). Irish University Press, Shannon. &ARK INDIAN STORE 119 QUIMBY. GEORGE I. 1937 Dated Indian Burials in Michigan. Papers of the Academy of Science, Arts and Letters, 23: 63-73. University of Michigan Press. 1966 Indian Culture and European Trade Goods. University o f Wisconsin Press, Madison. SIMONS. WALTER E. 1969 The Silversmiths of Old Detroit, Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Graduate Division, Wayne State University. SULLIVAN, JAMES (ED) 1922 The Papers of Sir William Johnson. 2523. University of the State of New York. TREATY OAKINDIAN STORE n.d. Catalogue IV. Jacksonville, Florida. TROWBRIDGE. CHARLES C. 1877 Detroit, Past and Present: In Relation to its Social and Physical Condition. Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections. I : 371-85. VICKERS. CHARLES 1923 Metals and Their Alloys. Henry Carey Baird & Company, New York. 1975 Catalogue No. 7 (March). Oklahoma City. PILLING. ARNOLD R. 1958 20 Wn 51. Ms. on tile, Department of Anthropology, Archeological Site Files, Wayne State University, Detroit. C. STEPHAN DEMETER COMMONWEALTH ASSOCIATES INC 209 E. WASHINGTON AVENUE JACKSON, MICHIGAN 49201