MC CommFdtn 2015 Report.indd - The Community Foundation for

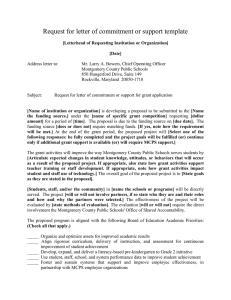

advertisement