standards for stun guns

advertisement

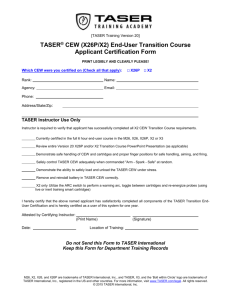

STANDARDS FOR STUN GUNS A Call for Uniform Regulations for Tasers in Michigan STANDARDS FOR STUN GUNS A Call for Uniform Regulations for Tasers in Michigan 1. Summary and Recommendations for Law Enforcement 2 2. The Court’s Taser Guidelines 4 3. Inconsistent Departmental Standards for Taser Use 7 4. Non-compliance with Departmental Standards 10 5. Non-compliance with Industry Standards 11 6. Risks of Perceived Racially Disparate Use of Tasers 13 7. Moving Away From Taser Use 15 8. Conclusion and Endnotes 16 Principal Author: Mark P. Fancher, ACLU of Michigan Racial Justice Project Staff Attorney Copyright 2013 - American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION is the nation’s premier guardian of liberty, working daily in courts, legislatures and communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution and the laws of the United States. AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF MICHIGAN 2966 Woodward Ave. Detroit, MI, 48201 313.578.6800 www.aclumich.org 1 STANDARDS FOR STUN GUNS: Summary and Recommendations When a taser is used on an intoxicated, handcuffed individual unwilling to place his body fully within a police car; or when tasers are used to break up fights between teenaged girls, many civilians might wonder why in such instances police use stun guns instead of their training, muscle and sweat to bring uncooperative individuals under control. This report is an invitation to law enforcement agencies to both adjust their taser policies and practices and to also address the public’s questions and concerns about these controversial devices. “Tasers”i are hand-held devices that shoot darts into clothing and flesh. An electric charge flows from the taser into the darts (or “probes”) through connecting wires, and then into the body. Alternatively, a law enforcement officer can remove the dart cartridge and apply the taser directly to the body to administer what is called a “drive stun.” Whether delivered by drive stun or by probes, the electric current affects the central nervous system and causes immediate, but temporary immobilization. The law says that under certain circumstances, police cannot use tasers on individuals who are in handcuffs, or who have been otherwise subdued. Yet, an extensive ACLU of Michigan review of police reports from across the state turned up records of incidents where police used tasers to force subdued but insubordinate individuals in custody to comply with police orders. Recommendations to Law Enforcement Agency Administrators The ACLU of Michigan has made additional observations as well that have led to the following recommendations to law enforcement agency administrators: 1. Ensure that all law enforcement personnel authorized to use taser devices are well-versed in the law’s guidelines and limits. Additionally, there should be routine monitoring of taser use to ensure compliance with legal requirements. 2. All Michigan law enforcement agencies that are unwilling to forego or abandon the use of tasers should limit the use of these devices to occasions when officers encounter “active aggression.” Law enforcement agencies should also have a shared definition of the term “active aggression.” 3. Law enforcement agencies should routinely monitor the use of tasers and undertake measures to ensure that officers who use these devices have a thorough understanding of the agencies’ policies and that they fully comply with the policies’ requirements. 4. Law enforcement agencies should establish policies that prohibit the use of taser devices on higher risk populations such as pregnant women, the infirm, the elderly, small children, and persons with low body mass index (‘BMI’). 5. Law enforcement agencies should routinely monitor the racial identities of those who are subjects of taser incidents, and they should identify trends and patterns that either reflects discriminatory practices, or that might lead members of the community to perceive that there has been discrimination. Further, law enforcement agencies should take immediate steps to correct practices 2 that are discriminatory, or to provide to the public information that explains the unavoidable circumstances that have created taser use patterns that imply discrimination. 6. Law enforcement agencies should establish as an objective the elimination of tasers from their arsenals and the adoption of alternative methods of addressing those circumstances that currently prompt the use of taser devices. Law enforcement agencies that have not used tasers should not acquire these devices for use by their officers. How This Report Was Compiled For more than two years, the ACLU of Michigan has used the Freedom of Information Act to request taser-related documents from more than forty Michigan law enforcement agencies. The documents that were produced for review disclose departmental policies and guidelines on taser use as well as narrative accounts of actual use of the devices in the field. Extended passages from police reports have been quoted in this document, and every effort has been made to avoid quoting narrative accounts out of context. Although only a few of the departments that were investigated are highlighted, the ACLU of Michigan has not made a judgment that these departments as a whole are qualitatively distinct from others. It is simply that officers employed by these departments have been involved in incidents that illustrate the ACLU of Michigan’s concerns about how and under what circumstances tasers have been or should be used. Departments may not have been named or discussed in this report for any of several reasons. Some departments responded to our requests for information by explaining that tasers are not part of their department’s arsenal. Other departments owned tasers but their officers had not had occasion to make significant use of the devices. Still other departments provided no records that indicated that officers had engaged in conduct that concerns the ACLU of Michigan. Finally, this report should not be regarded as a scientifically-designed, representative snapshot of taser use by law enforcement agencies throughout the state. This document has instead spotted several “red flag” incidents that may or may not be isolated, and that law enforcement leadership is urged to review and consider. 3 THE COURT’S TASER GUIDELINES The courts have placed limits on when police can use tasers. In the case of Austin v. Redford Township Police Department,ii a man was arrested, handcuffed and told to sit in the backseat of a police car. He sat on the backseat, but when he refused to put his legs in the car, he was repeatedly threatened with a taser.iii An officer then administered a drive stun to the man’s chest twice. In deciding whether the officer could be granted qualified immunityiv for using the taser while the subject was handcuffed and seated in the back of the police car, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals noted that: “Defendants do not challenge the district court’s holding that the law is clear in this Circuit that the use of force, including a Taser, on a suspect who has been subdued is unreasonable and a violation of a clearly established right.”v However, in addition to challenging the factual account given by the arrestee, the defendants raised: “…a further, purely legal argument that this Circuit’s precedent on the use of excessive force on subdued and unresisting subjects is irrelevant to situations involving non-compliance with police orders. Instead, they argue that [the officer’s] two discharges of his Taser in order to gain compliance with his order for Austin to put his legs in the police car did not violate any clearly established constitutional right.” vi In response to the defendants’ argument, the Sixth Circuit concluded: “There is no evidence or allegation that Austin was belligerent, threatening or assaulting officers, or attempting to escape. …[It] is well established in this Circuit that the use of nonlethal, temporarily incapacitating force on a handcuffed suspect who no longer poses a safety threat, flight risk, and/or is not resisting arrest constitutes excessive force. [citation omitted] ‘Even without precise knowledge that the use of the [T]aser would be a violation of a constitutional right,’ on these facts, [the officer] ‘should have known based on analogous cases that [his] actions were unreasonable. [citation omitted] Defendants’ legal argument that this Circuit’s precedent on the use of excessive force on subdued and unresisting subjects is irrelevant to situations involving noncompliance with police orders fails.” vii The following incidents as described in reports on file with referenced Michigan law enforcement agencies also involve the coercive use of tasers on civilians under circumstances that are arguably similar to those present in the Austin case. While the actions of these officers may or may not have violated governing law, the significance of these incidents is that they suggest the possibility that there are officers who either disregarded the legal limitations on taser use, or were not fully aware of them. These officers apparently were not reluctant to engage in actions that, if not illegal, were comparable to the actions of the officers in the Austin case. 1. “Ofc. [name withheld] and I did get [suspect] sat down in the back of the patrol vehicle, however his feet were outside of the patrol vehicle. Ofc. [name withheld] and I both gave verbal direction to get into the patrol vehicle or he would be tased. [Suspect] continued to kick and keep his feet out of the patrol vehicle. Ofc. [name withheld] again warned [suspect] 4 if he would not get into the patrol vehicle he would tase him. [Suspect] continued to not comply with our orders at which point Ofc. [name withheld] did drive stun [suspect] in the leg.” - taken from an East Lansing Police Department incident report dated 2/13/11 2. “…At that time [suspect] once again tried to turn around and face Ofc. [name withheld] and I at which point we did take [suspect] to the ground then secured the handcuffs. At that point we did pick [suspect] up and carried him backwards to our patrol vehicle. Ofc. [name withheld] and I told [suspect] to get into the back of the patrol vehicle, however he refused to get in. Ofc. [name withheld] told [suspect] once again to get into the back of the patrol vehicle, however [suspect’s] body became very rigid and he refused to get into the vehicle. Ofc. [name withheld] delivered three knee strikes to [suspect’s] L leg’s common peronial. [Suspect] still refused to get into the vehicle at which point Ofc. [name withheld] displayed his taser and did drive stun [suspect] one time in the L thigh. At that point we were able to get [suspect] into the back of the patrol vehicle to transport back to the jail.” - taken from an East Lansing Police Department incident report dated 3/13/11 3. “…Ofc. [name withheld] and I then got suspect out of my patrol vehicle, took a handcuff off his R wrist, put his arms behind his back and again handcuffed him, checked the cuffs for tightness and double locked them, then I went to place suspect back in the rear of my patrol vehicle, he would not get into the rear of my patrol vehicle. I first tried two distractionary knee strikes to his common peronial on his R leg. The suspect still would not get in the rear of my patrol vehicle at that time. I did take my taser out. I took the cartridge off the taser and used the taser in the drive-stun mode. I did drive-stun suspect in his L thigh for approx. one to two seconds. Suspect then did sit down on the rear of my patrol vehicle and I did shut the door.” - taken from an East Lansing Police Department incident report dated 10/9/11 4. “Prior to entering the Kalamazoo County Jail, I was attempting to obtain information from the suspect for the booking sheet. During that time the suspect continually used his phone which he had taken from his pocket and was attempting to call people using the speaker phone. The suspect was lying in the back seat and he would bring his hands to the side of his body to where he could dial and/or talk. I told the suspect that he needed to stop using the phone so that I could get the information however he refused to do so. I gave him several warnings to stop using the phone and to listen to me so that we could get through the booking process however he continued to use the phone. I told him on two separate occasions that if he didn’t hang up the phone I was going to come back and retrieve the phone from him. At that point he stated, “So what,” that he was going to jail anyway and there was nothing more we could do to him. I attempted to continue asking the booking questions however the suspect again used the phone and got a hold of somebody and started to talk rather than answer my questions. I then got out of the vehicle, opened the back door, and attempted to take the phone from the suspect’s hands. The suspect held onto the phone very tightly and would not release the grip on the phone. I told him to release the phone and he refused. At that point I pulled my taser out and released the cartridge and again told the suspect to release the phone. The suspect again refused to do so. I gave him one more 5 opportunity and after refusing to release the phone I then gave him a short burst of the taser on his left leg.” - taken from a Kalamazoo Township Police incident/investigation report dated 1/5/12 5. “…I grabbed a hold of her right hand near the wrist area and brought her right hand behind her back. She was then handcuffed. I then attempted to escort her to [a police] vehicle and she began resisting at this time, yet again. She would move her legs out in front of her and had to be physically carried by myself and [another officer] to his vehicle. At this point, I activated my COBAN system, opened the back seat door of [the police] vehicle and told [suspect] to get in the back seat and she did not do so. I provided her with multiple instructions and warnings to get into the back seat. She did not do so. At this point, I did remove the cartridge from my taser…and again told [suspect] to get into the vehicle. She again did not do so, at which point I did administer a drive stun to [suspect’s] upper left arm. She immediately fell into the vehicle…” - taken from a Battle Creek Police Department report dated 8/8/09 In each of these cases, it is quite possible that actions by law enforcement officers to force compliance by subjects in custody were warranted. The issue, however, is whether the officers involved were fully aware that the court has ruled specifically on the issue of using taser devices to force compliance. RECOMMENDATION We recommend that law enforcement administrators ensure that all law enforcement personnel authorized to use taser devices are well-versed in the law’s guidelines and limits. Additionally, there should be routine monitoring of taser use to ensure compliance with legal requirements. 6 INCONSISTENT DEPARTMENTAL STANDARDS FOR TASER USE The Michigan Commission on Law Enforcement Standards (MCOLES) is responsible for developing materials used to train police officers. MCOLES publishes and distributes to Michigan’s law enforcement agencies a document titled: “Subject Control Continuum: A Training Guide for Escalation and Deescalation of Subject Control.” It features a graphic that depicts the full range of actions that might be taken by a civilian along with the corresponding appropriate responses by a police officer. The document suggests that if a civilian engages in “inactive resistance,” the response should be “officer presence/verbal direction.” If there is “passive resistance” the response should be use of “compliance controls.” When there is “active resistance” there should be “physical controls” used in response. In cases where there is “active aggression,” “intermediate controls” should be used. Finally, if an officer confronts a “deadly force assault,” there should be a “deadly force response.” The graphic includes a caveat that states: “It is not possible for these Training Guidelines to cover all of the possible situations that occur within the law enforcement officer’s job. Therefore, this continuum is offered as a general training guide for using force in confrontation or arrest situations. The officer must understand that situations occur where the escalation and/or de-escalation of resistance is sudden, and the officer’s appropriate response may be located anywhere along the continuum, but it must represent an objectively reasonable response to the perceived threat posed by the subject.” By design the continuum does not attempt to second-guess officers who find themselves in situations that demand a response. It merely suggests that their actions be “…‘objectively reasonable’ in light of all the facts and circumstances confronting the officer at the time the force is used.” Consequently, there is no specific guidance provided about how or when tasers should be employed. Some law enforcement agencies have not taken the flexible approach followed by MCOLES. They have instead developed more specific policies and guidelines for taser use. For example: The Battle Creek Police policy dated June 1, 2010 states: “Application of the Taser is allowed to overcome resistance at the defensive resistance level on the use of force guide. Note: Officers may deploy at a lower level based upon the totality of the circumstances…” The department’s policy places “defensive resistance” at a level below active aggression, and it is defined by the department’s policy as: “Physical actions which attempt to prevent an officer’s control, such as pulling away, stiffening, or fleeing, but not directed at harming officers.” The taser use policy for the Ann Arbor Police Department dated January 23, 2006 provides in part: “The Taser is an intermediate weapon system. In a situation where the subject is offering passive resistance, it should only be used as a last resort. If used on a passively resisting subject, officers must be able to articulate that empty hand control options, including lifting and carrying, if appropriate; a.) Have been attempted and failed and b.) can be reasonably expected to continue to fail and c.) any further attempts can be reasonably expected to cause injury to the subject or officers involved.” 7 The Adrian Police Department’s taser policy provides that tasers may be used when there is “active physical resistance.” That term is defined by the department’s policy as: “Subject makes physical evasive movements to defeat the Officer’s attempt at control. Physical evasive movements may be in the form of bracing or tensing, attempts to push/pull away or not allowing the Officer to get close to him/her.” In the policy, “active physical resistance” is a stage below “aggressive physical resistance.” Although the East Lansing Police Department’s taser policy characterizes tasers as “intermediate weapons” which, according to the MCOLES subject control continuum should be used in response to “active aggression,” the policy states: “The X26 Taser has application where the subject’s actions constitute Active Resistance or Active Aggression.” (Active resistance is a level below active aggression and the MCOLES continuum calls for use of “physical controls” in response to it rather than use of intermediate weapons which, as far as this department is concerned, includes tasers.) The taser policy for the Schoolcraft County Sheriff’s Department states: “The [taser] is listed in the force continuum at the same level as OC spray; after soft hands. As such, [tasers] have application where the subject’s actions constitute Active Resistance or Active Aggression, or where the officer believes lower forms of empty hand controls will be inadequate…” The law enforcement agencies referenced above and others have demonstrated a preference for more specific guidelines for the use of tasers, notwithstanding the more flexible continuum published by MCOLES. However, the inconsistency of these policies among the various police departments has the potential to cause confusion and uncertainty both within the law enforcement community and in the general public. If a law enforcement agency is committed to maintaining tasers as part of its arsenal, the ACLU of Michigan believes tasers are most appropriately used at the active aggression level (which is just short of a “deadly force assault”) for several reasons. First, the courts (as previously noted) prohibit use of tasers on individuals who have been restrained. This means that as a threshold matter a person targeted by a taser must be in some way active. As noted above, there are degrees of activity that range from passive resistance (e.g., a subject goes limp or becomes dead weight) to active resistance (e.g., the subject pulls or pushes away) to active aggression (e.g., the subject physically advances toward the officers and physically strikes or wrestles), and presumably tasers might lawfully be used at any of those levels under the proper circumstances. However, tasers have also been the focus of considerable controversy, with concern revolving primarily around the effect of the devices on the human body. The ACLU of Michigan has reached no conclusions one way or the other about the effect of tasers, if any, on human health. However, there are others who still raise questions about the safety of tasers. Even a manufacturer has issued warnings about the possible hazards of using these devices on certain populations. All of this suggests the prudence of limiting use of tasers, at least at the time being, to those circumstances when there are no alternatives. 8 For those police departments that use tasers, the occasion when it will be most reasonable to use the devices is when officers are being physically attacked (i.e. in cases of active aggression) and other less than deadly force tools and weapons will be ineffective. RECOMMENDATION Based on the foregoing, we recommend that all Michigan law enforcement agencies that are unwilling to forego or abandon the use of tasers limit the use of these devices to occasions when officers encounter “active aggression.” Law enforcement agencies should also have a shared definition of the term “active aggression.” 9 NON-COMPLIANCE WITH DEPARTMENTAL STANDARDS Even if law enforcement agencies disagree about when it is appropriate to use tasers, it might be expected that officers will at least comply with the policies of their respective employers. Apparently, that is not always the case. For example, the Genesee County Sheriff’s policies and procedures on taser use state that the devices should not be used on occasions when a subject is engaged in “passive resistance.” The policy defines passive resistance as when: “…the subject resists control through passive, physical actions. Example: Passive Resistance is usually in the form of a relaxed or ‘dead weight’ posture intended to make the officer lift, pull or muscle the subject to establish control, as in a sit-down strike.” The policy goes on to give officers permission to do otherwise after using discretion and considering “the totality of the circumstances.” Nevertheless, the following report excerpt describes use of a taser on a prisoner who arguably engaged in an act of passive resistance. “…I told [inmate] to put her oranges [jail uniform] on. She refused to do so, saying ‘I’ll put them on when I feel like it.’ I told her that getting dressed was not up for debate and she needed to do so now. She failed to comply with my verbal commands. [A sergeant] told her to comply or she would be tased. [The inmate] wrapped up in her blankets and hid under the bed. [A deputy] opened the door to [the inmate’s] cell and she was told to come out from under the bed. She refused to do so. [A sergeant] dry (sic) stunned [the inmate] and [a lieutenant] pulled her from under the bed.” - taken from a Genesee County Sheriff Department report dated 1/22/09 On another occasion when a subject engaged in what was at least a subdued, non-threatening course of conduct, the reporting officer wrote the following in his report: “…as the vehicle went into the ditch the airbags did deploy and [a deputy] observed the driver attempting to open the vehicle door. [The deputy] then exited his vehicle, went around the left side of the vehicle and observed the driver was already out of the vehicle and standing there. [The deputy] ordered the subject to the ground with loud verbal commands to get on the ground. The subject failed to comply with the orders and stood in the ditch in the open door of the vehicle. It was at this time that [the deputy] deployed his taser aiming center mass with the taser. One probe struck the subject’s left chest area and one probe was in his groin area.” - taken from a Genesee County Sheriff Department report dated 8/30/08 RECOMMENDATION We recommend that law enforcement agencies routinely monitor the use of tasers and undertake measures to ensure that officers who use these devices have a thorough understanding of the agencies’ policies and that they fully comply with the policies’ requirements. 10 NON-COMPLIANCE WITH INDUSTRY STANDARDS A document published by Taser International (a manufacturer) that is labeled “Important ECD viii Product and Safety and Health Information” states that its purpose is to “…present important safety warnings, instructions, and information intended to reasonably minimize hazards associated with ECD deployment, intended use, effects, side effects, and environment of use.” The document highlights a wide variety of physical conditions that might make a person susceptible to serious injury or death if they are targeted by a taser. One section of the document is titled: “Higher Risk Populations.” It states the following: “ECD use on a pregnant, infirm, elderly, small child, or low body mass index (‘BMI’) person could increase the risk of death or serious injury. ECD use has not been scientifically tested on these populations. The ECD should not be used on members of these populations unless the situation justifies possible higher risk of death or serious injury.” While there are likely various law enforcement agencies that have used tasers on higher risk populations, the files of the Battle Creek Police Department contain several reports of incidents where tasers were used on middle school and high school students. This prompts concerns because the growth rates of children vary, and it is possible that some children in their teens still fit the physical profile of what Taser International would regard as a “small child.” Likewise, because of the special body weight circumstances of children, an officer’s visual observation is not a method of accurately determining body mass index (BMI). “BMI must be determined and plotted on the appropriate growth chart for the appropriate age.”ix A University of Kansas School of Medicine study concluded: “…our data showed medical professionals and trainees were unable visually to assess a child’s BMI for age weight status accurately. At best, classification of children by visual assessment can be described as inconsistent.”x It is unknown whether concerns about weight, height and body mass index were relevant or considered by the officers in the incidents described below, but these incidents did involve juveniles (including a 14year-old), and the fact that children are sometimes targeted for taser use suggests the need for policies that address concerns about higher risk populations. Excerpts from several incident reports follow: 1. [During a fight between students] “All three of us were giving commands for [a 15-year-old] to stop. [Another student] yelled out ‘I surrender I am not fighting anymore’ and held up his hands in a surrender motion. [Still another student] continued in his attempt to choke and punch [the 15-year-old] as myself and [another officer] attempted to separate [the 15-yearold]. After repeated commands, [the 15-year-old] was given a contact shot with the Taser X26 to the right side. The first contact shot did not have any affect (sic) on [the 15-year-old] and he continued to fight. I then gave him a second shot at which time [the 15-year-old] did cease and surrender.” - taken from a Battle Creek Police Department report dated 11/7/11 11 2. “I then walked up to [the 16-year-old] after she had ranted and raved and went to arrest her at which time she swung around and began throwing punches. I was hit twice in the face with a closed fist at which time I then took [the 16-year-old] to the ground to place her into handcuffs at which time she continued to kick and punch. After several attempts to get her to turn over on her stomach and put her hands behind her back had failed, I then drew my taser from the holster striking [the 16-year-old] in the lower body, hitting her in the right upper thigh with the taser prongs.” - taken from a Battle Creek Police Department report dated 3/6/09 3. “I observed two females actively fighting each other with a large crowd gathering around. I attempted to deploy the taser in attempts to strike both females with the prongs from the taser. There was a second delay in deploying the taser which caused the prongs to miss their target. I then after seeing that the prongs did not hit anyone, removed the cartridge and did a dry (sic) stun on [the 17-year-old] in the abdomen at which time I advised her to turn over on her stomach and place her hands behind her back after being tased, she did comply at which time Officer [name withheld] then handcuffed her to the rear. I then moved back towards Champion St. where my patrol car was at which time I did observe Lt. [name withheld] who had arrived on scene attempting to handcuff another female who was actively resisting at which time she was dry (sic) tased in the lower back. She was later identified as [a 16-yearold]. After being dry (sic) stunned, she did comply where she was then handcuffed to the rear and placed in the rear of a patrol car. [A 14-year-old] who was also being taken into custody by Officer [name withheld] was also resisting, trying to hand her cell phone off to subjects in the crowd and failing to comply, put her hands behind her back, was also dry (sic) tased with the taser in the lower back and shoulder. After being tasered twice, she did comply.” - taken from a Battle Creek Police Department report dated 2/9/09 It is not suggested here that the students should not have been physically restrained and subdued. The issue is instead whether use of tasers to gain physical control must be informed, and in some cases limited by the manufacturer’s advisory. RECOMMENDATION We recommend that law enforcement agencies establish policies that prohibit the use of taser devices on higher risk populations such as pregnant women, the infirm, the elderly, small children, and persons with low body mass index (‘BMI’). 12 RISKS OF PERCEIVED RACIALLY DISPARATE USE OF TASERS Historically, communities of color have had disproportionate rates of contact with law enforcement personnel. A report published by the National Conference of State Legislatures noted: “African Americans, Hispanics, Asians, Pacific Islanders and Native Americans comprise a combined one-third of the nation’s youth population. Yet they account for over two-thirds of the youth in secure juvenile facilities.”xi The report goes on to say: “Police practices that target low-income urban neighborhoods and use group arrest procedures also can contribute to disproportionate minority contact. [Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention] arrest rate statistics illustrate that African American youth are arrested at much higher rates than their white peers for drug, property and violent crimes.”xii Given the disproportionate law enforcement contact with communities of color, there is a risk of actual or perceived racially disproportionate use of tasers. This can have significant consequences for police/community relations. Any suspicion or resentment that might routinely flow from disproportionate contacts might be inflamed by the fear and intimidation that tasers tend to trigger. To move beyond speculation about these matters, the ACLU of Michigan directed Freedom of Information Act requests to several law enforcement agencies and requested, among other things: “all documents that indicate the race, gender and age of all persons against whom [tasers] were actually deployed during 2011 and 2012.” The responses to this request are instructive. Not surprisingly, in Benton Harbor, where the population is almost 93 percent black, all seven reported taser incidents involved black subjects. Equally unsurprising was the fact that right across the river in St. Joseph, where the population is almost 88 percent white, all four taser incidents involved white subjects. While the potential for controversy is greater in areas where populations are more racially mixed, complaints about bias are less likely in a city like East Lansing where the population is 78.4 percent white and 78 percent of those who were subjects of taser incidents were also white. Nevertheless, the use of a taser on a black East Lansing High School student in 2010 triggered a community-wide controversy and prompted questions and concerns about race and diversity.xiii Likewise, there is no guarantee that there will be no controversy even in cases where there is “equal” use of tasers. In Kalamazoo, about 50 percent of those targeted for taser use were white, and about 50 percent were black. However, the white population is about 71 percent, and blacks make up about 21 percent of the population. This means that even though there was equal use of tasers for both groups, blacks were targeted at a rate that is disproportionate to their representation in the population. The same is true in Auburn Hills, where four of seven taser incidents involved white subjects, and the remaining three were black. Although the numbers are roughly equivalent, blacks make up only 13 percent of the Auburn Hills population. 13 The potential for suspicions about racial bias are even greater in a city like Battle Creek where nearly 75 percent of the population is white, but four out of five of the taser incidents involved black subjects. In cases like this, a law enforcement agency should not limit its concern to public perception. There should be genuine efforts to identify the circumstances that are responsible for the racial imbalance, and unless the racial pattern was unavoidable, there should be a willingness to make necessary systemic changes that will ensure that taser use is not discriminatory. RECOMMENDATION We recommend that law enforcement agencies routinely monitor the racial identities of those who are subjects of taser incidents, and they should identify trends and patterns that either reflect discriminatory practices, or that might lead members of the community to perceive that there has been discrimination. Further, law enforcement agencies should take immediate steps to correct practices that are discriminatory, or to provide to the public information that explains the unavoidable circumstances that have created taser use patterns that imply discrimination. 14 MOVING AWAY FROM TASER USE The Warren Police Department has had the misfortune of having had its personnel involved in two incidents where civilians have died after having been shot by tasers (it has not been established that the tasers were the cause of death in either incident). In one incident police said a 27-year-old man died after a taser was used during his attempt to escape from a police car. In another incident, police said a 16-year-old was chased into a vacant house and then shot with a taser when he appeared to make a renewed effort to escape. He reportedly blacked out and was never resuscitated. The Warren Police Department has discontinued use of tasers, but the deaths are not cited as the reason for this change. The decision was reportedly prompted by a letter from the taser manufacturer that warned of the expiration of the devices. “Police Commissioner Jere Green cited multiple reasons for his decision to order all patrol officers, shift commanders and others on the street to turn in their Tasers. Warren’s topranking police administrator emphasized he will not risk officers’ safety if there’s potential for a delay when a Taser trigger is pulled; that use of Tasers failed to produce the desired results nearly a quarter of the time they were deployed; and that he doesn’t have the money in his budget to replace the aged models with the new ones.”xiv If the deaths in Warren were not the reason for dropping tasers, they probably did not make continued use of these devices any more attractive. In the final analysis, there are a number of taser-related issues that should give pause to law enforcement agency administrators whose departments use tasers; or who are considering use. A number of these concerns are outlined in this document. There are still other issues related to the continuing evaluation of the effect of tasers on the body. In weighing the benefits of tasers against the detriments, the ACLU of Michigan concludes that because of the high potential for non-compliance with legal, organizational and industry standards, as well as perceived if not actual racial discrimination, from a civil rights/civil liberties standpoint, communities are better served by law enforcement agencies that do not use tasers. There is no doubt that some law enforcement personnel have concluded that tasers are useful, others as expendable. It is worth noting that in Warren the decision to drop the tasers did not trigger resistance in the department. “Cpl. Matt Nichols of the Warren police training division said nearly all officers eagerly turned in their Taser and only about three officers expressed concern... ‘Once we explained it… they freely handed it over.’” xv In addition, a number of law enforcement agencies in Michigan that have not used tasers in recent years, including police departments that serve Detroit, Flint, Hartford, Muskegon Heights, Muskegon and Shelby. RECOMMENDATION We recommend that law enforcement agencies establish the elimination of tasers from their arsenals and the adoption of alternative methods of addressing circumstances as an objective. Law enforcement agencies that have not used tasers should not acquire these devices for use by their officers. 15 CONCLUSION AND ENDNOTES The frequency and manner of use of tasers in Michigan appears to be inconsistent and unstandardized. The consequence has been practices that may violate governing law and that may be contrary to guidelines and warnings issued by manufacturers. Public perception of tasers and the officers who use them may be negatively affected by circumstances that imply, if not demonstrate arbitrary and discriminatory use of these devices. Law enforcement agencies are well-advised to seek compliance with all applicable laws and standards and to fully address actual and potential public concerns. i The term “taser” is used as a generic term in this report to refer to all conducted energy devices regardless of whether they were manufactured by Taser International. ii 690 F.3d 490 (6th Cir. 2012) iii Earlier, during this same encounter, the subject had been tasered twice and attacked at least once by a police dog. iv “Qualified immunity protects government officials performing discretionary functions unless their conduct violates a clearly established statutory or constitutional right of which a reasonable person in the official’s position would have known.” Austin, 690 F.3d at 496. v Id. vi Id at 497. vii Id at 499. viii “ECD” stands for Electronic Control Device, one of several generic terms used for taser devices. ix Using the BMI for Age Growth Charts,” (http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/growthcharts/training/modules/module1/text/module1print.pdf x “Visual Recognition of Child Body Mass Index by Medical Students, Resident Physicians, and Community Physicians,” by Ahlers-Schmidt, Kroeker, et al., Kansas Journal of Medicine (2010). xi “Minority Youth in the Juvenile Justice System: Disproportionate Minority Contact,” Jeff Armour and Sarah Hammond (National Conference of State Legislatures) p. 4. xii Id. xiii “Tasing of Student Leads Parents to Speak Out at School Board Meeting,” by Amber Johnson-Weeks (Entirely East Lansing) http://entirelyl.wordpress.com/2010/12/10/tasing-c xiv “Warren Police Department Drops Tasers After Shocking Letter From Manufacturer,” By: Norb Franz, The Oakland Press (6/10/12) xv Id. 16