The Miller Theorem and the Frequency Response of the Common

advertisement

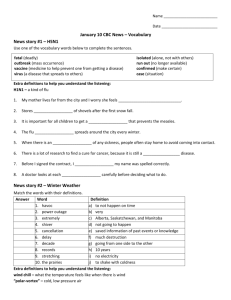

The Miller Theorem and the Frequency Response of the Common Emitter Amplifier L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 1 A useful approximation: The Miller Theorem • Consider a shunt admittance connected between the input and output of an inverting voltage amplifier of gain G. VIn Iin • Y IF - IF VOut In Out -G I1 -G I2 Iout (1+G)Y (1+1/G)Y Assuming that Y does not affect the gain, KCL at the input says that: iin = i1 + iF = i1 + ( vin − vout ) Y = i1 + ⎡⎣(1 + G ) Y ⎤⎦ vin iout = i2 − iF = i2 − ( vin − vout ) Y = i2 + ⎡⎣(1 + 1/ G ) Y ⎤⎦ vout • • L2 This is the same current as we would get if we connected Y(1+G) in parallel to the input and Y(1+1/G) in parallel to the output (on the right) Note that this is an approximation; Y always changes the gain, unless Z out // Z L = 0. Nonetheless, very often it is a good approximation. Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 2 An application of the Miller theorem Input impedance of the inverting amplifier (if op-amp has zero Yin): R2 R1 vin G Vout Z in = R1 + R2 (1 + G ) We can even use the Miller theorem to calculate the gain of this circuit for finite op-amp gain G: Av = R2 / ( G + 1) ) vout −GR2 − R2 = −G = , lim Av = vin R1 + R 2 / ( G + 1) R1G + R1 + R2 G →∞ R1 This is the correct answer for the closed loop gain as we shall later see! SF1.6p34 L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 3 The small signal model the of BJT The model below is useful to frequencies of up to 100s of MHz The model is strictly valid for B-E voltage variations smaller than VT=25mV. To analyse a circuit: – Each transistor in a circuit is replaced by this model – The “base spreading resistance” RBB is lumped with the thevenin impedance of the signal source. It is not shown explicitly in these notes. What does RBB do: • RBB is responsible for most of the noise of transistor amplifiers • RBB is responsible for the power gain rolling-off at high frequencies • RBB is often ignored at “low” (f < MHz) frequencies • • • L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 4 BJT model: impedances and transconductance • The large signal BJT equation gives the transconductance: ⎛ V ⎞ I C = I 0 eVbe / Vth − 1 ⎜1 + CE ⎟ I 0 eVbe / Vth VA ⎠ ⎝ kT Vth = B 26 mV at room temperature e ∂I I gm = C C ∂Vbe Vth ( • However, since IE=(1+1/β)IC , Rπ = • ) ∂VBE = β VT / I C = β / g m ∂I B Same equation gives output conductance: GCE = 1/ RCE = L2 Autumn 2009 ∂I C I = C ∂VCE VA E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 5 BJT model Capacitances BC junction is reverse biased: – depletion capacitance – overlap capacitance • BE junction is forward biased: – depletion capacitance – storage (diffusion capacitance) – overlap capacitance CBE = CBE 0 + C j + CD • CE capacitance is small – overlap capacitance CCE CCE 0 • Fringing/Overlap capacitances: CBC 0 , CBE 0 , CCE 0 • Junction capacitance: – Reverse biased diode – M=1/2-1/3, from doping – Φ approx 0.8V – M, Φ usually determined from two bias points • L2 CBC = CBC 0 + C j • Diffusion capacitance – from transit time Autumn 2009 Cj = C0 ⎛ VBE ⎞ ⎜1 − ⎟ Φ ⎠ ⎝ CD = g mτ T E2.2 Analogue Electronics M , τ T = 1/ 2π fT Imperial College London – EEE 6 An important figure of merit: the BJT Current gain and the transit frequency fT The transistor is connected as a current amplifier: • Driven by a current source • Driving a current meter fT is the frequency at which the current gain drops to unity. fT is usually specified by the transistor manufacturer as a figure of merit. fT is a rough estimate of the highest frequency at which the transistor can be used as an amplifier. Typically fT / 10 is this highest frequency. L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 7 An important figure of merit: the BJT Current gain and the transit frequency fT iB = vBE ( s ( CBE + CBC ) + 1/ Rπ ) ⎫⎪ ⎬⇒ iC = g m vBE ⎪⎭ β0 iC gm g m Rπ = " h fe " = = = iB s ( CBE + CBC ) + 1/ Rπ 1 + sRπ ( CBE + CBC ) 1 + s β 0 / 2π fT where fT = β0 2π Rπ ( CBE + CBC ) the current gain is h fe ( f ) = = β gm gm , since: Rπ = 0 2π ( CBE + CBC ) 2π CBE gm β0 ⇒ 1 + j β 0 f / fT lim h fe = f > fT / β 0 fT 1 with fT = 2πτ T f fT allows the easy calculation of CBE + CBC since gm only depends on the collector bias current! Note that CBE>>CBC so knowing fT defines CBE L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 8 The Common Emitter amplifier Load Source Amplifier Model parameters: L2 Autumn 2009 ⎧ ∂I C IC = = g ⎪ m ∂VBE VT ⎪ −1 −1 −1 ⎪ ⎛ ∂ ( IC / β ) ⎞ ⎛ ∂I B ⎞ ⎛ ∂I C ⎞ β ⎪ R β = = = = ⎨ π ⎜ ⎜ ⎟ ⎟ ⎜ ⎟ ∂ ∂ ∂ V V V gm ⎝ BE ⎠ ⎝ BE ⎠ BE ⎝ ⎠ ⎪ −1 ⎪ ⎛ ⎞ I ∂ VA ⎪R = C ⎪ CE ⎜⎝ ∂VCE ⎟⎠ IC ⎩ VT = kT / q = 25mV at 290K=17C E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 9 The Common Emitter amplifier (2) Combine VS , Z S , Rπ into a Thevenin circuit: Rπ VS = VS 1 = VS Rπ + Z S 1 + Z S Yin Rπ Z S ZS = RS 1 = Rπ / / Z S = Rπ + Z S 1 + Z S Yin Consider RCE and Z L together: R2 = RCE / / Z L = RCE Z L ZL = RCE + Z L 1 + Z LYout and note that Z S = RS + RBB L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 10 The Common Emitter amplifier (3) Gain: vout ∂V2 Vs1 − gm Z L 1 Av = g m R2 = ≡ =− vs Vs ∂Vs (1 + RsYin ) (1 + Z LYout ) If Yin= 0 and Yout = 0 this is the familiar: vout Av = ≡ − gm Z L vs Note that lowercase letters represent small signal variations, i.e. differentials L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 11 The Common Emitter amplifier (4): Input and output impedance −1 Input Impedance: ∂VBE ⎛ ∂I B ⎞ =⎜ Z in = ⎟ = Rπ ∂I B ⎝ ∂VBE ⎠ −1 Output Impedance: L2 Autumn 2009 Z out ∂VC ⎛ ∂I C ⎞ = =⎜ ⎟ = RCE ∂I out ⎝ ∂VCE ⎠ E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 12 Frequency response of the Common Emitter amplifier If we momentarily neglect CBC this would be the same as before but with: Input Impedance: Rπ 1 Z in = = Rπ / / CBE = 1 + jωCBE Rπ Yin Output Impedance: Z out = We still have: A V = L2 Autumn 2009 RCE 1 = RCE / / CCE = 1 + jωCCE RCE Yout vout − gm Z L 1 v − gm Z L = and out = G = vs (1 + RsYin ) (1 + Z LYout ) vB (1 + Z LYout ) E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 13 Dealing with CBC ICBC In the absence of CBC we know that: the current through CBC is: vout − gm Z L =G= vB (1 + Z LYout ) I CBC = jωCBC (VB − VC ) = jωCBC (1 − G ) VB = jωCBC (1/ G − 1) VC We can account for CBC by introducing an additional input “Miller” admittance: YM ,in = jωCBC (1 − G ) and an additional output “Miller” admittance: YM ,out = jωCBC (1 − 1/ G ) L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 14 Frequency response of the CE amplifier VS1 and RS1 is the Τhevenin equivalent of RS VS and Rπ Use the Miller Theorem to get: with C2 = CBE + (1 + G ) CBC (1 + G ) CBC and C3 = CCE + (1 + 1/ G ) CBC CBC The low requency gain from V1 to V2 is: G = − g m R2 − g m Z L L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 15 Frequency response of the CE amplifier (2) the gain of this amplifier is: − gm dV2 R2 G = = dVS 1 1 + sRS 1C2 1 + sR2C3 (1 + sRS 1C2 )(1 + sR2C3 ) input pole output pole If the gain is large the input pole can be at a much lower frequency than the output pole: τ IN = RS 1C2 = ( Rπ / / RS ) ( CBE + (1 + G ) CBC ) RS (1 + G ) CBC ( since RS Rπ ) τ OUT = R2C3 = ( CBC (1 + 1/ G ) + C CE ) ( RCE / / Z L ) CBC Z L (since CBC CCE ) The gain-bandwidth product of this amplifier is: G = g m R2 g m Z L ⎫ g m R2 1 G ⎪ . lim GBW . 1 1 ⎬ ⇒ GBW = G →∞ BW = 2 2 (1 ) 2 π π π R C R C + G R C S 2 S BC S BC 2π RS 1C2 2π RS C2 ⎪⎭ This is independent of G! if τ in > τ out The tiny CBC and the source impedance can define the gain-bandwidth product of the CE amp. This suggests that feedback is at work! Note that the input pole will be at a lower frequency than the output pole if G RS 1 > R2 ⇒ g m RS 1 R2 > R2 ⇒ g m RS = β RS / Rπ > 1 L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 16 Importance of the gain-bandwidth product the gain of the CE amplifier is: − gm dV2 R2 G = = dVS 1 1 + sRS 1C2 1 + sR2C3 (1 + sRS 1C2 )(1 + sR2C3 ) input pole output pole One of the two pole frequencies is usually much lower than the other. We then say that we have a dominant pole amplifier whose frequency response is: Av ( s ) = G0 G0 = for a DC gain G0 and a bandwidth 1 + sτ 1 + jωτ ωB = 1/ τ We have already seen that in the limit of large G0 the Gain-Bandwidth product: GB = G0ωB = G0 / τ is independent of the amplifier gain. We will see later in the course that this is a very general result which applies to all one pole feedback amplifiers regardless of how they are constructed. L2 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 17