Commercial Warranties - Are They Worth The Money?

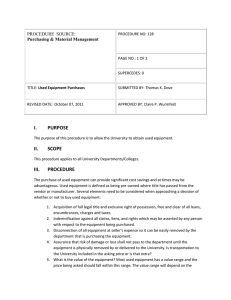

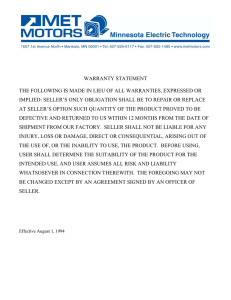

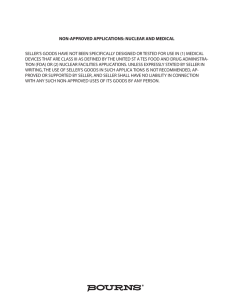

advertisement