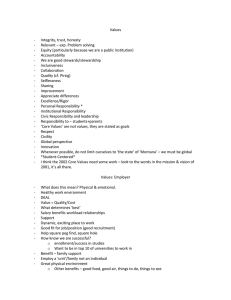

mapping legislative accountabilities

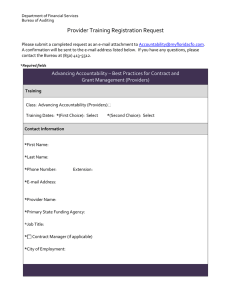

advertisement