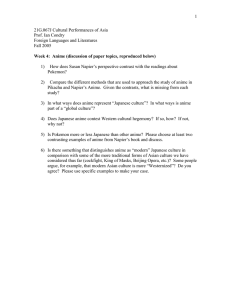

“lost in translation”: anime, moral rights, and

advertisement