The Too-Much-of-a-Good-Thing Effect in Management

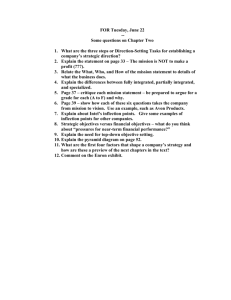

advertisement