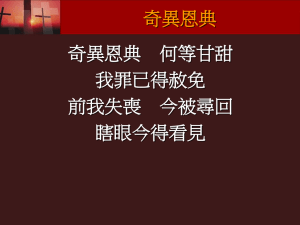

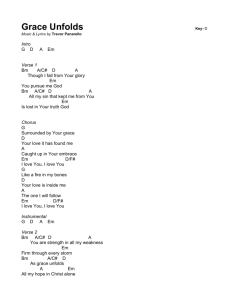

-1- The Grace of God Grows Great Enough: Doctrinal Grace and

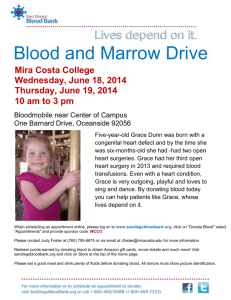

advertisement