International Journal of Community Currency Research

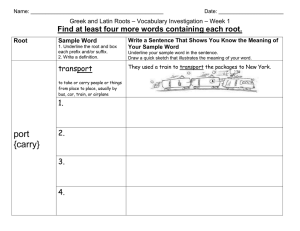

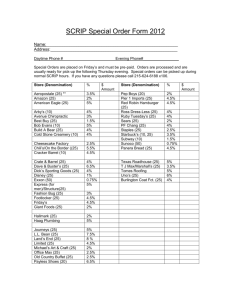

advertisement