Secondary English Language Arts

Table of Contents

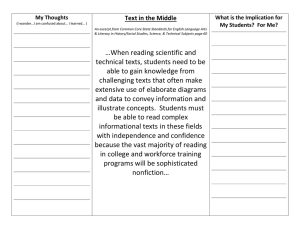

Diagram: Literacy

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Familiar Concepts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Genre, Mode, Affordances . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Immersion Into Texts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Integrated Profile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Other Key Concepts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Continuity from Secondary Cycle One to Secondary Cycle Two . . . . . 3

Differentiation in the Classroom . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Making Connections: SELA2 and the Other Dimensions of the QEP 4

Connection With the Broad Areas of Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Connections With the Cross-Curricular Competencies . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Connections With the Other Subject Areas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

How the Three Competencies of the SELA2 Program Work Together . . 5

Integrated Teaching-Learning-Evaluating (TLE) Context . . . . . . . . . 6

Development of Competency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

A Literate Learning Environment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Opportunities for Integrated Reading and Production . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Role of the Teacher . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Working With Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Monitoring the Development of Critical Literacy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Integrated TLE Context: Keys to Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Repertoire of Required Genres . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Diagram: Competency 1 Talk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Competency 1 Uses language/talk to communicate and to learn . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Focus of the Competency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Thumbnail Sketch of the Key Features . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Key Features of Competency 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Evaluation Criteria . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Secondary English Language Arts

End-of-Cycle Outcomes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Development of the Competency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Program Content . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Diagram: Competency 2 Reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Competency 2 Reads and listens to written, spoken and media texts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Focus of the Competency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Thumbnail Sketch of the Key Features . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Key Features of Competency 2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Evaluation Criteria . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

End-of-Cycle Outcomes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Development of the Competency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Program Content . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Diagram: Competency 3 Production . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Competency 3 Produces texts for personal and social purposes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Focus of the Competency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Thumbnail Sketch of the Key Features . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Key Features of Competency 3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Evaluation Criteria . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

End-of-Cycle Outcomes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Development of the Competency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Program Content . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

Appendix: Terms and Concepts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

Selected Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

Québec Education Program Languages Secondary English Language Arts

LITERACY

STUDENT:

LITERACY PROFILE

– Repertoire of written, spoken and media texts

– Stategies and processes

– Experiences, history, values and system of beliefs

– Meanings that are socially and culturally designed, produced and interpreted

GENRE/MULTIGENRE

– Representations of people, gender, race, events, information, attitudes, beliefs

– Structure, Mode(s) Codes, Conventions

– Meanings that are socially and culturally designed, produced and interpreted

CONTEXTS FOR

INTERPRETATION AND PRODUCTION

– Situations that integrate the Talk,

Reading and Production competencies

Québec Education Program Languages Secondary English Language Arts

Making Connections: Secondary English Language Arts and the Other Dimensions of the Québec Education Pr ogram (QEP)

Uses language/talk to c ommuni c ate and to learn

Se co nd ar y re a r e

En gl ish

Reads and listens

La ng ua ge

Art s

La ng ua ge s

Ma them

CO

M

PETEN

atics, Scien ce and Technolo

CIE

S

Uses creativity

INT

E

LL

EC

T

U AL

Exercises critical judgment gy

Adopts

M

ETH

OD

OL

OGIC

effective

Solves problems

Uses information

Health and

Well-Being

work methods

Personal and

Career Planning

Uses

AL

Soc

CO

M

P

ETE

NC

I ial

E

S

information

Construction of to written, spoken student’s identity

Construction

and

communications

technologies and media texts

Sc ie nc es of student’s

Citizenship and

STUDENT

world-view

O

C Community

D ev elo

M

M

U

N

I

C

A

T

I pm

Communicates appropriately

O

N

-

RE

L

A

TE

D ent

COM

P

ET

E

N

C Y

Life

Empowerment

Media

Literacy

Environmental

Awareness

and Consumer Rights and Responsibilities

Cooperates with others

PER

S ON

AL A

ND

Achieves his/her potential

T

EN

CI

E

S

C

OM

PE

SO

C IA

L

Ar ts

Ed uc at io n

Personal Developme nt

Aims of the QEP

Broad Areas of Learning

Cross-Curricular Competencies

Subject Areas

Subject-Specific Competencies in Secondary English Language Arts

Québec Education Program

Produ c es texts for personal and so c ial purposes

Introduction

The Secondary English Language Arts program for Cycle Two (SELA2) is first and foremost a literacy program. As such, it prepares students to make intellectual and aesthetic judgments, raise questions, articulate their thoughts and respect the ideas of others. The noted Brazilian educator Paulo

Freire described literacy as knowing how to “read the word and the world.”

Language is both a means of communicating feelings, ideas, values, beliefs and knowledge, and a medium that makes active participation in democratic life and a pluralistic culture possible. In order for our students to develop literacy in a world of rapid social, cultural and technological change, we need to take the time to connect learning about the social

SELA2 is a literacy program that focuses on fluency in the reading and production of spoken, written and media texts.

purposes of language to the worlds of all the students we teach, so that they understand language-learning as the development of a repertoire of essential strategies, processes, skills, knowledge and attitudes. These are the

“basics” that make it possible for students to continue to learn throughout their lives–the foundation of literacy. For this reason, the SELA2 program is grounded in the language, discourse and genres that our students encounter in the world and focuses on the development of fluency in the reading and production of spoken, written and media texts.

The goal of any literacy program must be to provide opportunities for students to experience the power of language as a way of making sense of their experience and of breaking down the barriers that separate individuals.

This program provides students with the opportunity to develop language competencies that respond to the realities of diverse situations, as well as the interpersonal and communication strategies that they require in order to become active, critical members of society. Drawing on a wide range of traditional, modern and contemporary texts, SELA2 also fosters an appreciation of a rich literary and cultural heritage.

Québec Education Program Languages

Familiar Concepts

The SELA2 program addresses a series of issues and concerns raised by our community since 1980. As such, it both revises and extends the content and orientations of its predecessor, the Secondary English Language Arts I to V program. In turn, there are several familiar elements: writing, responding to and interpreting texts as processes of making meaning; collaborative learning as a means of cultivating a community within the classroom; learning-bydoing (i.e. rather than by hearing about it); learning in contexts or situations that are relevant and developmentally appropriate; and an orientation that honours the principles of pedagogical differentiation and inclusion.

Genre, Mode, Affordances

In the SELA2 program, specific spoken, written and media texts are studied as genres. The traditional definition of genre has been extended to include social purposes and functions, so that students learn not only the structures and features (i.e. mode, codes and conventions) of specific genres, but also the inherent social messages and meanings they carry. As well, the SELA2 program promotes the reading and the production of those texts that fall into the category of multigenre, since they combine two or more genres into a single text.

Word, sound and image are different modes of representation used in the communication process. Each mode of representation has its own codes and conventions,

Word, sound and image have their own specific codes and conventions, or grammar. That is to say, there are specific grammars associated with media and spoken texts, as well as with or grammar.

written texts. When texts combine modes of representation, as is true of feature stories in newspapers which combine word and image, they are said to be multimodal. The SELA2 program promotes the reading and production of multimodal texts, as well as those that feature a single mode of representation, such as conventional written texts.

› 1

Chapter 5

Secondary English Language Arts

Finally, given the focus in the SELA2 program on literacy, students are expected to exercise their understanding of different genres and modes by working in contexts that require them to select the genre and mode that best suit the demands of a specific context. In order to do this with any degree of success, they must draw upon their knowledge of what different genres and modes “afford,” in terms of the “fit” between a given genre, or mode, and the meaning(s) or message(s) they wish to communicate. The decisions students make in a given context, or situation, also draw on their understanding of the connection between a text and its social function, i.e.

how it is used in school, in the workplace, or in society. Also, the student who has developed control of different modes and genres may adapt a particular genre or mode to a novel purpose, such as selecting journal entries to reveal the inner workings of a character as s/he attempts to resolve a conflict. This concept–that different genres and modes offer distinctive potentials, or possibilities, in a given context–is referred to as the affordances 1 of a genre or a mode.

In order to provide extensive opportunity for students to explore the affordances of different genres and modes, the writing and media competencies of the Cycle One program have been integrated into a single

Production competency in SELA2. This step is also necessary in light of the rapid evolution of the types of texts we encounter in all aspects of our daily lives. Our students need to learn to distinguish the affordances of print as well as to select modes or combinations of modes that best suit their own production intentions and the demands of a given context. It has long been accepted that reading-writing connections enhance literacy development and

SELA2 promotes reading-production connections for this reason.

Immersion Into Texts

The SELA2 program extends several concepts that were introduced in Cycle

One. Literacy involves the conscious application of strategies, processes and knowledge: immersion into texts promotes conversations about specific genres and how they work. As students engage in an inquiry process to discover the connection between the codes and conventions of a text and

1. See also Gunther Kress, Literacy in the New Media Age .

Québec Education Program its meaning(s), they learn that every text is a deliberate, social construct. As they consider how a writer persuades a reader, they learn that meanings are designed with very specific intentions in mind. Immersion into texts appears in each of the three competencies of SELA2 since it is an essential step in the development of literacy.

Integrated Profile

The Integrated Profile is the heart of the SELA2 program and is designed to document evidence of the development of competency. As stated in the introductory chapters of the Québec Education Program

(QEP), the development of competency takes place over time as students work with different content and resources

A “moving portrait” of literacy development.

in increasingly demanding contexts. The Integrated Profile is a “moving portrait” of students’ learning throughout Cycle Two. It is integrated insofar as it contains evidence of students working in contexts where the language arts are integrated, i.e. where the three competencies of the SELA2 program are called upon in an integrated way. Although the actual form the profile takes is at the discretion of the teacher, the profiles are organized and maintained by the students. This task is also connected to their learning about how to work with information-based texts, in which students’ own texts represent information about their learning. The content of the Integrated Profile also corresponds to evaluation instruments the teacher intends to use, such as rubrics that describe different levels of competency development. Possible forms of an Integrated Profile include a collection of integrated projects; a folder that includes a range of evidence about a student as a reader and producer of spoken, written and media texts; and a portfolio.

The Integrated Profile is described in detail in the Program Content section of Competency 1 (Talk): Integrated Profile: Showing the Competencies in

Action. It is a vital feature of the dialogue between the teacher as a literacy expert and the student, and is an essential resource in the development of competency. In the latter instance, it should be noted that the capacity to use self-evaluation as a means of monitoring one’s own learning is characteristic of competent behaviour. This metacognitive skill develops in contexts where individuals are asked to articulate the processes and

› 2

Chapter 5

strategies they have used to accomplish a specific task. When such opportunities are provided on a regular basis, students become more conscious of their strengths and those areas that need more work. In other words, these conversations about learning foster student autonomy and the development of literacy. For this reason, the Integrated Profile and the student-teacher conferences in which they are examined play an essential role in the SELA2 program.

Other Key Concepts

In addition to these elements, the program also includes specific reading and production strategies that promote competency: the notion of the reader’s stance; the opportunity to read young adult and traditional literature, as well as popular and information-based texts; emphasis upon the structures, features, codes and conventions of specific genres, including those that convey information; and the production of multimodal texts. The

SELA2 program promotes the importance of reading and production to develop personal interests, as well as for pleasure and to learn; the use of technology in reading and producing texts; enrichment in the form of extended activities, such as literary festivals; classroom drama as an interpretive and problem-solving strategy; and formal occasions for selfevaluation as a means for students to monitor their progress, reflect on their learning and establish future learning goals.

Continuity from Secondary Cycle One to Secondary Cycle Two

The SELA2 program is part of a learning continuum that began with the

Elementary English Language Arts program (EELA) and continues through the Secondary English Language Arts program for Cycle One (SELA). Both the EELA and SELA programs focus on literacy, i.e. competency in reading, writing and the media, and in the use of talk to communicate and to learn.

Throughout the last three years of secondary education, the SELA2 program concentrates on the consolidation of the essential strategies, processes, knowledge and abilities that support lifelong learning.

Students arriving in Cycle Two have developed reading, interpretive, writing, production and collaborative strategies appropriate for their age and for

Québec Education Program Languages their stage of cognitive and social development. At the beginning of Cycle

Two, teachers should expect the majority of their students to still be most competent with narrative genres. As well, students are used to drawing on their own experiences and knowledge to make sense of different kinds of texts, and have developed a literacy profile that includes reading and production preferences, familiarity with a modest range of different genres, collaborative skills and processes for responding to and producing texts, and an initial understanding of working with information-based texts.

2 Students expect their Cycle Two teachers to appreciate these prior experiences and to value matters of personal choice with regard to reading material and the content of the texts they produce. A familiar audience of family, friends and peers was the focus for writing and production in both the EELA and SELA programs; in Secondary Cycle Two, students learn to move gradually from a familiar audience to those audiences that are found in a more public landscape and in which there is a greater distance between writer/producer and audience.

Differentiation in the Classroom

Any literacy program must be created with a range of students in mind. In the SELA2 program, the balanced nature of the three competencies makes it possible for

With its emphasis on spoken, written and media texts, SELA2 offers teachers many teachers to accommodate the varied needs, interests, abilities and learning styles of all the students they teach.

ways of differentiating instruction.

Indeed, the principles of differentiation lie at the heart of the QEP. When teachers differentiate instruction, they modify contexts for learning, the content to be learned and aspects of the learning process. With the inclusion of spoken and media texts, young adult literature, a range of texts to be produced, the important role of talk in all aspects of the learning process, and an emphasis on conferencing and student self-evaluation, the

SELA2 program provides a solid foundation for differentiated instruction.

3

2. For specific information, including End-Of-Cycle Outcomes for the first two years of secondary school, teachers are encouraged to consult the SELA program for Cycle One.

3. For additional information, see Carol Ann Tomlinson, The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners .

Secondary English Language Arts

› 3

Chapter 5

Making Connections: SELA2 and the Other Dimensions of the QEP

Connections With the Broad Areas of Learning

The broad areas of learning provide contexts that are grounded in students’ lives and the realities they face, both now and in the future. In fact, the broad areas of learning form the bridge between students’ everyday lives, the school community and wider social

The broad areas of learning deal with major realities. English Language Arts supports the development of the broad areas of learning by offering rich contemporary issues.

Through their specific communication contexts in which to explore issues and by providing a collaborative community in which students approaches to reality, the various subjects learn to express themselves and fulfill their potential.

illuminate particular aspects of these issues and thus contribute to the development

For example, Media Literacy encourages students to be actively involved in both reading and producing media texts that respect individual and collective rights. Since of a broader world-view.

literacy for life is the foundation of SELA2, this media component is developed throughout the program as students work collaboratively in “real world” conditions, both analyzing the ways the media construct reality and using different media to construct their own views of the world.

Environmental Awareness and Consumer Rights and Responsibilities asks students to consider the ethical aspects of their behaviour as consumers and to adopt responsible behaviour with regard to their surroundings. The

SELA2 classroom provides a learning environment in which students can investigate, in a critical and proactive manner, a variety of topics, such as globalization, sustainable development, consumerism and advertising. In this context, students participate actively in the classroom and the world, put facts into perspective and analyze the major issues of the day.

Connections With the Cross-Curricular Competencies

The cross-curricular competencies comprise the essential attitudes, knowledge and resources that students need to be competent and successful in all areas

Québec Education Program of life. They are closely linked to employability skills at a time of transformation in the world of work, including the increased expectations of future employers. The crosscurricular competencies focus on strategies and processes linked to “learning-how-to-learn” in a variety of situations and across the curriculum. For this reason, SELA2 addresses aspects of each of the cross-curricular competencies as they pertain to the discipline.

The cross-curricular competencies are not developed in a vacuum; they are rooted in specific learning contexts, which are usually related to the subjects.

Intellectual

In the SELA2 program, the uses of information are addressed explicitly in all three competencies. Competency 1 (Talk) features problem-solving as students reinvest these strategies for various purposes; Competency 2

(Reading) looks at the interpretation of texts through the lens of critical judgment, especially as concerns texts that argue and persuade. Competency

3 (Production), with its focus on a wide range of texts, enhances the development of students’ creativity.

Methodological

All three competencies of SELA2 provide links to the two methodological cross-curricular competencies, offering contexts to enhance their development.

Students engage in a range of activities in which the key features of CCC

5: Adopts effective work methods are fundamental. CCC 6: Uses information and communications technologies is addressed as students read and produce multigenre and multimodal texts and as they learn to identify the affordances, or potentials, of different modes and genres.

Personal and social

In the SELA2 classroom, contexts for learning address CCC 8: Cooperates with others in direct, immediate ways as students express their own points of view, accommodate the views of others and participate as members of

› 4

Chapter 5

a team. Conversely, CCC 8 also makes a significant contribution to the way students use language to learn. Since critical literacy in SELA2 has been defined as reading the word and the world, each of its competencies focuses on the connections between texts and the worlds of students, encouraging them to take risks in order to learn. CCC 7: Achieves his/her potential contributes to the SELA2 competencies by supporting the importance of connecting texts to their social and cultural function(s) and by stressing the degree to which the development of confident, autonomous individuals depends upon the support and encouragement of others.

Communication-related

The correspondence between CCC 9: Communicates appropriately and SELA2 underscores the critical role of language, discourse and genre in making lifelong learning possible. More precisely, both CCC 9 and SELA2 address modes of communication, the contexts in which communication takes place, target audiences and the connection between the purpose for communication and the structures and features of texts.

Connections With the Other Subject Areas

English Language Arts is both a discipline and a language of instruction.

As such, its connections to other subject areas are both explicit and complementary. With its emphasis on spoken, written and media texts, SELA2 supports the other subject areas by teaching students about the social purpose(s) and function(s) of texts, including features of particular discourse communities. In the latter case, students are better able to appreciate the vocabularies of different disciplines. Because of the emphasis in SELA2 on the meanings that different texts convey, students acquire literacy strategies that apply to any subject area. For example, SELA2 makes a direct connection to Ethics and Religious Culture by examining ethical issues related to life in a democratic society inherent in many of the texts that students read, since this kind of discovery is deeply related to the development of critical literacy.

English Language Arts has a long tradition of interdisciplinary study. In particular, SELA2 is linked to history and the social sciences in terms of the literature and other texts that students read, insofar as these texts have a sociocultural and historical context. When students are working with

Québec Education Program Languages information-based texts or as they develop a research process, the topics, themes and messages they encounter are usually cross-curricular in nature and often pertain to areas traditionally associated with history, the sciences and the arts. In these instances, the connections between SELA2 and other subjects is a reciprocal one, resulting in interdisciplinary contexts for teaching and learning. Also, the broad areas of learning and the cross-curricular competencies provide contexts for interdisciplinary projects, as is the case when students develop an ethnographic study. Here, depending on their focus, students may be developing surveys, interviewing people, studying the local history of their community and using the media and ICT to conduct research. Clearly, in order to complete this project, they need to integrate the knowledge they

Reality can rarely be understood through the have gained in numerous subject areas, while also drawing on the capacity to adopt effective work methods rigid logic of a single subject; rather, it is by and cooperate with others.

To enhance learning in their own discipline, ELA teachers bringing together several fields of knowledge that have traditionally called upon other subject areas, particularly the arts. ELA teachers often take students we are able to grasp its many facets.

to live theatre and/or dance productions, as well as to museums and concerts, in an effort to enrich their students’ cultural experiences. Therefore, SELA2 continues the proud tradition of fostering a love of performance, art, theatre and music.

How the Three Competencies of the SELA2 Program

Work Together

Since SELA2 is a critical literacy program, its competencies are interdependent and complementary ; similarly, the key features of each competency are nonhierarchical and nonchronological in nature. Therefore, it is possible to enter the program through any one specific competency. The visuals accompanying each competency illustrate how it contributes to the development of critical literacy. The integration of the competencies, together with the flexibility of the key features, accommodate different pedagogical styles and a wide range of instructional contexts. Teaching to competency requires the creation of multiple occasions for students to practise their growing fluency and to consolidate literacy strategies and skills.

› 5

Chapter 5

Secondary English Language Arts

Integrated Teaching-Learning-Evaluating (TLE) Context

Development of Competency

Competency develops and manifests itself in situations, or pedagogical contexts, that require students to mobilize the resources in their repertoire and apply them effectively. In other words, competency is more than simple recall, rote learning or a cumulative set of information and skills. Competent learners can modify, adapt, innovate and transfer their declarative, strategic and procedural knowledge to different situations for a variety of purposes.

This is largely because students have already had many opportunities to work with strategies, processes, procedures and knowledge in different combinations and for different purposes. The kinds of TLE contexts, or

Literate individuals situations, that teachers create to support their students’ development of competency are always planned with a demonstrate competency in a wide range of clear focus in mind. This section describes the conditions that are essential to the development of critical literacy situations and possess a repertoire of reliable and that are common to all TLE contexts or situations.

Common to these learning situations is their capacity to knowledge and skills.

motivate students, as well as challenge them.

A Literate Learning Environment

The goal of the SELA2 program is the development of a confident learner who finds in language, discourse and genre a means of coming to terms with ideas and experiences, and a medium for communicating with others and for learning across the curriculum. Students must be immersed in a rich, literate classroom environment that promotes the important value placed on literacy in this culture, in their school and by their teachers. As students read and produce texts for pleasure and to learn, they must have access to a classroom and/or school library that offers an excellent range of materials that interest and appeal to adolescents. This range of texts is critical to students’ development in each of the three competencies of the program.

Technology and other similar resources must also be made available, since the program promotes their use.

Opportunities for Integrated Reading and Production

Students learn to make connections between mode, genre and context in classrooms where they are actively engaged in reading, interpreting and producing a range of texts. They explore and work with new strategies and processes principally, though not exclusively, related to the structures and features of different modes of representation as these are found in different genres. The representational modes of word, sound and image have their own specific affordances and the development of literacy is rooted in knowing when to choose a mode and genre in light of one’s intentions . As well, literate readers recognize that a writer or producer has chosen specific modes and genres to establish some kind of relationship with the audience , e.g. promote a point of view, encourage an action or response, create a virtual world, etc. Therefore, it is vital that the contexts or situations in which students are producing texts demand that they make similar choices. As well, attention is paid to the transfer of strategies and knowledge from one context to another and to different modes and media, i.e. from the media to print and vice versa, from print to speech and vice versa. Language-inuse, in contexts where students are encouraged to take risks and responsibility for their own learning, is the means for the development of versatile meaning-making processes and effective language strategies.

Role of the Teacher

The development of literacy is both an individual achievement and a social skill, since we learn how language works in the fabric of family, school, community and culture. In the Cycle Two classroom, the teacher plays

In the SELA2 classroom, the literacy of the teacher is the essential resource.

Québec Education Program

› 6

Chapter 5

a number of important roles, one of the most important being that of a trusted adult who models literate behaviours and practices. The teacher has a direct influence not only on the values students associate with literacy, but also on their understanding of how language constructs meaning(s) in school and out in the world. The teacher is also instrumental in setting the tone of a teaching-learning environment. Learning language and using language to learn involve engaging students in activities that speak to the issues, themes and experiences that mark adolescent lives. In this way, literacy interweaves linguistic, textual and social knowledge, so that learning in our discipline is grounded in the understanding that language and texts are essential resources that we rely upon throughout our lives.

Talk is central to individual and social processes of making meaning, as students learn to extend their views, opinions, preferences and knowledge in dialogue with the teacher and their peers. Varied opportunities to use talk to learn and to communicate reinforce the sense of community in the classroom, the centrality of the meaning-making process and the importance of exchanges with peers and teacher to the development of students’ literacy. In dialogue with others, students develop the ability to represent situations, circumstances and subjects that lie beyond their direct experience.

The tone of teaching-learning is also interactive and collaborative. Students come to understand that the codes and conventions of different genres are sociocultural in nature by participating in situations that require them to draw on prior knowledge to move to new uses of spoken, written and media language. Collaborative projects and activities teach students to respect the different views of their peers, to express their own views with confidence and to use effective work methods, while also providing students with an important means of discovering the different functions of texts. For example, students in the second year of Cycle Two often grapple with the structure of written argument, even though they show a great deal of strategic ability when defending their opinions in class discussions or formal debates. It makes sense, then, to draw on this understanding as a basis for teaching students how to structure an argument in a written text.

Working With Information

The structures and features of information-based texts are different from those employed in literary and popular texts, and incorporate their own

Québec Education Program Languages rhetorical features. For this reason, information-based texts are studied in all three competencies of the SELA2 program, with an emphasis on those texts that target adolescents in particular and that present content that is related to the broad areas of learning. It is anticipated that students work with information in more deliberate and skillful ways as a result of the integration of the three competencies, in such activities as immersion into texts, interpretation of a variety of information-based texts, oral presentations, classroom debates and so forth.

Monitoring the Development of Critical Literacy

Reflexivity is a capacity that is actively learned while students mobilize the resources—strategies, processes, knowledge—in their repertoire in a specific context or situation. The capacity to reflect-in-action indicates control of the resources and self-monitoring strategies the students have acquired and is fundamental to the development of critical literacy. Over the three years of

Cycle Two, students learn to reflect systematically on their literacy and learning, developing the essential skill of monitoring their individual progress in English language arts over time. Opportunities to reflect on and to selfevaluate progress, with the teacher’s guidance and support, are frequent. In order to support the development of critical literacy, the content of each of the three competencies is integrated so that reading, for example, is connected to talk and the production process. Literacy is a whole system of communication and the separate competencies represent the parts that make up the whole.

A record of progress and development over the three years of the cycle is maintained in students’ Integrated Profiles.

These profiles represent samples of students’ use of language/talk to think and to learn, and of their processes

For students to develop literacy, they must be given opportunities to reflect upon their for interpreting and producing spoken, written, media and multimodal texts for different audiences and in a range learning and selfevaluate their progress.

of TLE contexts or situations. They also include samples of self- and peer-evaluations. The content for student-teacher conferences, using each student’s Integrated Profile as the focal point, is found in Competency

1 (Talk): Integrated Profile–Showing the Competencies in Action–and calls upon learning in all three competencies of the SELA2 program.

› 7

Chapter 5

Secondary English Language Arts

Integrated TLE Context: Keys to Development

There are some common characteristics of the SELA2 classroom over the three years of Cycle Two that support the development of students’ competency.

They are adapted to correspond to the developmental growth of students throughout the cycle, while also providing a framework for planning a range of learning and evaluation situations (LES) that integrate the three competencies of SELA2.

These common characteristics are:

– Reading, interpretation and production processes as specified in the SELA2 program

– Opportunities for students to work both individually and collaboratively

– Regular and sustained periods for students to read and produce texts for pleasure and to learn

– Regular opportunities for students to contribute to the classroom community, e.g. working in peer response groups, providing feedback, participating as member of a team, initiating projects and activities

– Opportunities for students to work in situations (LES) that integrate aspects of the Talk, Reading and Production competencies

– Opportunities for students to read and produce a balance of spoken, written and media texts, as well as multigenre and multimodal texts

– Access to texts that reflect personal interests and preferences, as well as those that expand students’ Integrated Profiles

– Access to additional resources, e.g. primary and secondary resources about a particular event, period of history, author

– Differentiation and student choice regarding projects, activities and the topics/subjects for reading and production

– Regular opportunities and time for students to reflect on literacy and learning

– Student responsibility for organizing and maintaining their own Integrated Profile

– Regular opportunities for students to self-evaluate

– Introduction of new learning that includes teacher-modelling and opportunities for students to apply what has been demonstrated

– Support and guidance from teacher throughout the learning process

– A balance of familiar and unfamiliar texts and TLE contexts

› 8

Chapter 5

Québec Education Program

Repertoire of Required Genres

Required Genres

Throughout Cycle Two, students are required to read and produce texts from each of the social functions listed below. The texts themselves are also compulsory, since all of them appear in the program content of one or more of the competencies of the SELA2 program.

In most cases, the chart makes no distinction between the texts that students read and those they produce: SELA2 is an integrated language arts program that promotes a reading-production connection in the classroom. It is anticipated that students are engaged in reading and interpreting texts for pleasure and to learn, as well as reading to learn how to produce texts and to foster the imagination. In other words, students read more widely than they produce over the three years of the cycle, and learn to draw on these reading-production connections to consolidate their understanding of the affordances of specific genres and modes. For this reason, the texts listed below have been categorized according to their dominant social function.

By the end of secondary school, students’ Integrated Profiles must reflect a balance of genres and modes, as well as a range of TLE contexts, or situations, in which different texts are read and produced.

Social Functions Texts

PLANNING texts are used to plan and organize our thoughts, ideas and actions, and to help us monitor our own learning.

Proposals, action plans, outlines and storyboards; field notes, transcripts, minutes and other informal notes including the results of individual and group brainstorming activities; self-monitoring texts such as rubrics or checklists

REFLECTIVE texts help us to reflect, think and/or wonder about life, current events, personal experiences, as well as to reflect on our actions and evaluate what we learn.

Class and small group discussions, including responses and interpretations of texts; rereading and presenting contents of the Integrated Profile, including self-evaluation conferences and written self-evaluations and reflections; peerediting and feedback conferences; journals such as reading logs, media logs, learning/process logs and/or writer’s notebook

NARRATIVE texts are one of the oldest forms for recording and making sense of human experience, as well as articulating the world of the imagination.

Reading: popular, mass-produced narrative texts such as magazines, graphic novels and film; young adult literature; novels, short stories, poetry and plays from classic, modern and contemporary literature

Production (spoken): improvisations, role play, storytelling; poetry readings, dramatizations of plays and other texts

Production (written/media/multimodal): script, story, personal narrative, poetry, narratives using different media such as print, radio, video, photography

Québec Education Program Languages Secondary English Language Arts

› 9

Chapter 5

Required Genres (cont.)

Social Functions Texts

EXPLANATORY texts answer the questions “why” and “how.” Describing a procedure and/or explaining social/natural phenomena, these texts allow people to share their expertise in a range of fields and form the basis of many texts from which we learn throughout our lives, such as textbooks and reference books.

Photo-essay with text, spoken explanations of a process, “how to” booklet/manual or video

REPORTS describe the way things are or were, conveying information in a seemingly straightforward and objective fashion. They focus on the classification and/or synthesis of a range of natural, cultural or social phenomena in order to name, document and store it as information.

Research reports, interview transcripts, news reports in different media

EXPOSITORY texts are constructed in deliberate ways and interpret some aspect of the world in a particular way . Whereas fictional texts may occupy a prominent place in our leisure time, persuasive and argumentative texts are central not only to leisure activities, as in reading newspapers, but also play an important role in postsecondary institutions, different professions and in the world of work in general.

Argumentative texts try to convince people of a point of view about a topic or issue through a logical sequencing of ideas and/or propositions.

Persuasive texts try to move people to act or behave in a certain way, including selling or promoting a product or ideology.

Action research plan, speech, editorial, book or film review, poster, debate, advertisements including public service announcements: print, radio, television. Texts that promote a particular argument or point of view such as documentary film and Internet sites. Essays dealing with personal and social concerns, as well as issues arising from literature.

› 10

Chapter 5

Québec Education Program

COMPETENCY 1 TALK

STUDENT:

INTEGRATED PROFILE

– Repertoire of genres and texts

– Stances and points of view

– Values and beliefs

– Knowledge and personal experiences

– Questions / critical judgment

– Tastes and preferences

– Purposes and intentions for communication

– Strategies and processes

GENRE/MULTIGENRE

– Social functions (purposes/intentions)

– Spoken, written, media texts

– Codes and conventions

– Constructed meanings, messages

– Representation of values and beliefs

– Mode/multimodal

– Affordances

TALK CONTEXTS

– Classroom as democratic community

– Ethnography project

– Independent units of study

– Inquiry and action research

– Collaborative talk groups

– Self-evaluation conferences

Québec Education Program Languages Secondary English Language Arts

› 11

Chapter 5

COMPETENCY 1 Uses language/talk to communicate and to learn

Focus of the Competency

Students entering Cycle Two bring with them a repertoire of communication and learning strategies, abilities and literate behaviours, developed from their experiences in the EELA and SELA programs. They are able to produce spoken texts that present ideas and information to a familiar audience in informal contexts, and can plan and shape communication to achieve specific purposes, selecting effective strategies from their repertoire. Also, with peer and teacher support, they are able to organize and carry out collaborative action research projects, assuming responsibility for their own learning in these contexts. Students can also plan and carry out independent units of study, and organize and present their profiles of work from all the competencies over the cycle. Most of these

By working in both informal and formal contexts, students processes and projects are continued in Cycle Two of the program, and therefore will be familiar to students.

develop new rhetorical strategies

However, new challenges are set that demand new ways of using spoken language to communicate and to learn, for communicating with different audiences.

and various learning contexts are designed specifically so that students may develop the necessary strategies to carry out these new demands. For example, there is a movement from the familiar, informal context, e.g. the classroom, with peers and teacher as audience, to a more formal one, e.g.

a school debate, with secondary students and teachers as audience. This change of context necessitates the use of a more focused and structured language, and the development of new rhetorical strategies to address different audiences. However, the kind of collaborative discourse called talk remains a necessary component of all the contexts in which students work, as it has been in both the EELA and SELA programs.

Research has shown that a more explicit style of spoken (and written) language, one less context-bound and more elaborated, is associated in our society with academic and professional success. In Cycle Two, students work toward the development of this kind of language by participating in numerous contexts where they examine the characteristics of spoken

Québec Education Program language, its various uses in the school, community and society, and the expectations of the different audiences that they address. As they move into more structured contexts, students learn to be aware of the changes needed in the level of language used, and to adjust their language resources accordingly—in other words, they develop a sense of register. By making these adjustments of register in many different contexts, students develop a more flexible form of language, one that can accommodate the demands of more complex communication and learning contexts. An important new emphasis for Cycle Two is the study of genres and their functions in our society. Students learn how genres are organized and structured, what conventions and rhetorical aspects are attached to them, what language resources are necessary,

Students study the genres and how their mastery is important to students’ future success. They study the uses, organization and language of explanation, reporting, argument/debate and requirements of the genres associated with spoken language, such as explanation, report, argument/debate persuasion with an emphasis on their social functions.

and persuasion. In collaborative settings, students develop a repertoire of strategies to construct the knowledge needed to produce texts in these genres, as well as strategies to collect data by researching and interviewing. In these contexts, they also develop an understanding of the appropriate use of research strategies.

Collaboration and inquiry-based learning remain a central part of this competency, as they were in Cycle One. Both these processes are essential ways of making meaning: collaborative talk, with its tentative and exploratory qualities, allows for the use of questioning and hypothesizing, of searching for answers, of playing with ideas, and provides an important way for students to assimilate and integrate new knowledge; inquiry-based

Inquiry-based learning focuses on how knowledge is really produced—how learning moves the focus from the view of knowledge as ready-made and transmittable “as is” from teacher to student or from text to reader to an exploration and demonstration of how knowledge is really produced—how questions are asked and data articulated.

› 12

Chapter 5

questions are asked, data accumulated and generalizations made. In projects such as ethnographic research, students follow these processes and apply these strategies to conduct original research in the school and community.

Both collaboration and inquiry-based learning also play an important role in Competency 2 (Reading) and Competency 3 (Production). For example, students work in collaborative groups to produce texts in all modes; discuss their interpretive responses to texts being read, viewed and listened to; and use collaborative talk with teachers and peers to discover what they know and want to write about. Both processes also require students to be immersed in a community of language users engaged in meaning-making in many different contexts.

This competency contributes actively to the development of the educational aims of the broad areas of learning. All of them are addressed and serve as important learning contexts for students, since these aims reflect personal and social concerns pertinent to their world and thus offer many areas for further investigation and development. Two of the broad areas of learning have special relevance. First, Career Planning and Entrepreneurship , whose educational aim is to enable students to make and carry out plans designed to develop their potential and help them integrate into adult society, has strategies for planning projects that are similar to those of this competency.

And Citizenship and Community Life , whose educational aim is to enable students to develop an attitude of openness to the world and respect for diversity, overlaps with the key feature of this competency that deals with the social practices of the classroom and community.

This competency also fully supports the development of all the crosscurricular competencies. Of particular importance is CCC 7: Achieves his/her potential , since an important feature of the Talk competency is the development of autonomy in students. CCC 7 is referred to in the Program Content dealing with social practices of the classroom and community, where strategies such as taking her/his place among others and making good use of her/his personal resources are a critical part of the growing autonomy of students.

As well, CCC 5: Adopts effective work methods is incorporated in the many tasks and projects that students undertake, because strategies such as analyzing and evaluating procedures and identifying available resources are essential to the success of any project. Finally, since interaction with others is one of the key features of this competency, it subsumes the focus of CCC 8:

Cooperates with others and its strategies, such as using teamwork effectively.

Québec Education Program Languages

Differentiation in the Classroom

A collaborative, project-based classroom uses the diversity of student abilities and interests as a positive resource. Students of all abilities benefit from a classroom environment where teachers and peers offer continuous support to the learner, where student interests and aspirations are respected and encouraged, and where student success is the ultimate goal of all concerned.

The classroom learning contexts are consciously designed to allow all students to develop the competency, and also to offer scope for differentiated learning. These contexts are complex enough to accommodate the varied abilities and learning styles of students, and are rich enough to challenge them to develop new insights. There are numerous opportunities to adjust or extend the required content: for example, students self-select topics and methods of development for their independent units of study and they maintain Integrated Profiles which include evidence of how personal choices and interests contributed to their growth over the cycle. In most cases, students and teacher negotiate the curriculum within the demands of the competency, and this collaboration ensures that the interests and the abilities of students are fully considered.

Thumbnail Sketch of the Key Features

Students expand their repertoire of resources

Students expand their repertoire of resources for use in all communication and learning contexts. They investigate the affordances of spoken language in order to discover its distinctive potential as a mode of communication. The as they participate in a range of activities, from action research to independent units aesthetic qualities of spoken language are examined by looking at their use in poetry and media texts. Students of study to presenting their Integrated Profile.

develop a range of rhetorical strategies to communicate effectively with an audience. For example, they understand that nonverbal resources such as facial expressions and gestures can be used to construct and emphasize meaning. Students also learn that a change of audience and setting influences the organization and presentation of spoken texts in many subtle ways and that, in these contexts, a change of register is required. As well, students examine the affordances of the required genres and their organizational and language conventions. They expand their range of resources for accessing information and collecting the data needed for use in specific genres, e.g. to support arguments. An important aspect of this

› 13

Chapter 5

Secondary English Language Arts

key feature is the conscious recognition by students that these resources are essential to effective communication and learning. Social interaction in various learning contexts is the emphasis of another key feature.

Collaborative talk groups and action research groups are the sites for the interaction, and these groups work in contexts where the audience, topic to be examined and genre are negotiated with the guidance of the teacher.

Collaboration is presented as a knowledge-building process: students learn how meaning is constructed through collaborative talk, and how communal knowledge is developed and presented in genres such as explanation, report, argument/debate and persuasion. Using an inquiry process, action research groups learn how to access information through research, interviews and classroom drama. Classroom drama is viewed as a different way of learning about an issue or problem: a way of examining complex issues by embodying other voices and points of view and by providing imagined possibilities for inquiry and reflection. An important aspect of this key feature is the examination of genres and their structures, through which students learn how genres act as forms of knowledge in our society, and how to use them effectively for their own purposes.

The social practices of the classroom and community are examined, and emphasis is placed on the use of teacher-student dialogue to support learning, to foster the development of students’ metacognitive abilities, and to encourage their autonomy. Students assume an active role in their own learning by developing a metalanguage to discuss their progress and by engaging in a process of self-evaluation and reflection. They plan and carry out independent units of study on self-selected topics, and share their findings with peers and teacher. They organize and maintain an Integrated

Profile containing work from all the competencies, and discuss it with the teacher in regular and ongoing evaluation conferences throughout the cycle.

As well, students examine the use of language for discussion and debate in the classroom and community, and the place of spoken language in the life of the school. To demonstrate their knowledge of the resources of spoken language and their use of strategies for collecting data, students conduct an exploratory ethnographic project in the school or community. An important aspect of this key feature is its emphasis on the growing autonomy of students who have developed the ability to evaluate what and how they are learning and to consider ways of putting this knowledge into action.

Québec Education Program

› 14

Chapter 5

Key Features of Competency 1

Establishes a repertoire of resources for communicating and learning in specific contexts

Investigates the affordances of spoken language as a mode of communication • Examines some of the aesthetic qualities of spoken language • Develops rhetorical strategies to achieve specific purposes • Examines the affordances of genres • Extends the range of strategies for collecting the data needed for use in specific genres

Uses language/talk to communicate and to learn

Participates in the social practices of the classroom and community in specific contexts

Investigates the uses of spoken language in the school and community • Plans and carries out independent units of study • Conducts exploratory ethnographic research • Organizes and maintains an Integrated

Profile of work over the cycle • Engages in a process of self-evaluation and reflection • Confers with the teacher in regular and ongoing evaluation conferences

Evaluation Criteria

Interacts with peers and teacher in specific contexts

Collaborates with peers to construct knowledge about how things are done

• Participates in collaborative action research groups using an inquiry process

• Applies procedural and meaningmaking strategies to achieve a purpose

• Contributes to team efforts as an interactive and critical listener

– Adapts resources and strategies to purpose and audience

– Collaborates to carry out an inquiry project

– Organizes information in a report for a specific audience

– Applies rhetorical strategies in a persuasive text

– Selects data-collecting strategies appropriate to the context

– Self-evaluates development as a learner

End-of-Cycle Outcomes

The student draws on a repertoire of resources to communicate and to learn in specific contexts. S/he demonstrates understanding of the affordances of spoken language by incorporating the aesthetic qualities of spoken language, such as sound qualities, into spoken texts for special effects. S/he uses rhetorical strategies to create a relationship with an audience and to achieve a desired purpose, and adapts these strategies in different contexts. As well, the student adjusts the register to meet the demands of a specific context, e.g. when presenting a spoken text in a more formal setting. The student uses knowledge of the affordances of genres when selecting one for a specific purpose. Also, the student draws on a range of strategies for collecting data for specific purposes.

The student interacts with peers and teacher in collaborative talk groups and action research groups. S/he selects from a repertoire of strategies those needed to support knowledge-building within the group, such as assuming the stance of a critical listener and negotiating meaning with peers by questioning and challenging different viewpoints. The student applies a process of collaborative inquiry to learn and think through talk, and participates in action research projects to examine problems and issues of both personal and social significance, e.g. consumerism, violence in schools, environmental issues. In these contexts, s/he applies strategies such as making and testing hypotheses, collecting and interpreting data, theorizing, and developing tentative solutions to problems.

The student is able to use the required genres and their conventions, e.g. can report on a topic to an audience and persuade an audience to act in a desired manner.

The student participates as a member of the classroom by assuming an active role in her/his learning and by evaluating her/his development as a learner. S/he designs an independent unit of study and presents it to peers and teachers in an organization of her/his choice. The student also organizes and maintains an Integrated Profile of work done in all the competencies of the program and presents it at regular student-teacher conferences. S/he uses a process of selfevaluation and reflection to examine her/his work over the cycle. S/he talks about the processes and strategies s/he uses for communicating and learning through talk, e.g. collaborating with peers, debating issues, interviewing. As well, the student initiates activities and projects that examine school and community language practices, e.g. an exploratory ethnographic research project.

By the end of Cycle Two, the student is a selfmotivated communicator and resourceful learner, one who has taken an active role in the classroom and community during the secondary school years.Through the many and varied negotiations with peers and teacher, the student has developed an individual voice and is confident in expressing opinions, raising

› 15 questions, articulating thoughts and making

Chapter 5 critical judgments.

Québec Education Program Languages Secondary English Language Arts

Development of the Competency

Throughout Secondary Cycle Two, students are a part of a classroom community of active and engaged language users. The teacher provides them with ongoing opportunities to participate in learning situations specifically designed to encourage and support development of the competency. These situations must involve significant tasks that increase in complexity over the cycle, demand an active mobilization of resources to accomplish them adequately, and encourage the development of autonomy in students. In the Talk competency, development is seen in three key areas: contexts for communication and learning, repertoire of resources, and integration of knowledge, resources and strategies. The charts that follow describe the kinds of teaching-learning situations that promote development in each of these areas.

There are some common characteristics of the ELA classroom over the three years of Cycle Two that support the development of all three competencies in SELA2. These are described in the TLE Context and promote the type of classroom environment in which the development of Competency 1 (Talk) takes place.

Contexts for Communication and Learning:

Producing Texts

To ensure the production of a variety of spoken texts over the cycle, the teacher structures contexts, or learning situations, such as the following: collaborative discussion groups, where students produce spoken texts in specific genres; action research groups, where students investigate authentic personal and social issues and produce action plans; independent units of study and self-directed research projects, where students negotiate topic, audience and methods with their teachers. In all these contexts, the teacher supports new learning experiences, and monitors the students’ growth and development as users and producers of spoken language.

Québec Education Program

› 16

Chapter 5

Texts

Genres

Topics

Year One

Explanation, Reporting,

Argument/Debate, Persuasion

Focus: exploration of the affordances of genres

See also Repertoire of Required Genres

Topics and issues of personal and social interest

Exploration of community and social issues

Year Two

Explanation, Reporting,

Argument/Debate, Persuasion

Focus: compare/contrast affordances of genres, in particular argument/debate and persuasion

See also Repertoire of Required Genres

Topics and issues of personal and social interest

Issues from larger social and cultural worlds

Year Three

Explanation, Reporting,

Argument/Debate, Persuasion

Focus: evaluation of differences in affordances of genres, in particular argument/debate and persuasion

See also Repertoire of Required Genres

Topics from personal, social, cultural and political worlds, including issues that present more intellectual challenges and require more extensive research

Many different contexts, both informal and formal

Contexts Familiar contexts in most cases

Possibility of more formal contexts

Familiar or informal contexts

More formal and structured contexts

Genre conventions

Familiar contexts: knowledge and strategies to shape texts; language requirements and registers of the different genres

Less familiar contexts: same as above, with teacher-modelling and guidance

Teacher-modelling of the conventions of the specific genres listed above

Teacher-modelling of organizational strategies to structure genres

Choice of spoken language strategies appropriate to genre, e.g. factual statements and precise language for a report

Teacher-modelling of known processes and strategies to suit context, e.g.

problem-solving strategies to resolve an issue

Familiar contexts: knowledge and strategies to shape texts; language requirements and registers of the different genres

Less familiar contexts: same as above, with teacher support, as needed

Experimentation with genre conventions necessary to present more complex issues, with teacher support

Adaptation of known organizational strategies to structure genres

Adjustment of spoken language strategies appropriate to the genre, e.g. registers and other rhetorical strategies

Use of known processes and strategies to suit context, e.g. using appeals to both reason and emotions to persuade an audience

Québec Education Program Languages

Demands of different communication contexts, e.g. knowledge, strategies, language requirements and registers

Use of genre conventions necessary to present more complex issues

Control of a repertoire of organizational strategies to structure genres

Selection of spoken language strategies appropriate to the genre, e.g. more conscious use of rhetorical strategies

Relevant processes and strategies to suit context, e.g. when reporting on a complex issue, develop knowledge from a variety of sources and organize material to suit the needs of the audience

Secondary English Language Arts

› 17

Chapter 5

Repertoire of Resources: Knowledge, Processes and Strategies

Throughout the cycle, students build a repertoire of resources by acquiring the knowledge, processes, strategies and attitudes presented in the Program

Content. Students draw from their repertoire when accomplishing tasks in various contexts. Since the acquisition of these resources is critical to the success of the student, the teacher provides many varied opportunities for students to construct knowledge and develop strategies that support the gradual development of their repertoire. The teacher impresses on students the importance of a repertoire that is expansive, relevant and organized, and finds many occasions to monitor its development. As well, the teacher models unfamiliar or difficult processes and strategies, and helps students integrate these new learning experiences.

In this way, students realize the importance of the teacher as a principal resource in the learning process.

Knowledge,

Processes,

Strategies

Knowledge: affordances of spoken language in group tasks

Year One Year Two

Codes and conventions of language needed for general communication acquired by continual use of spoken language for a variety of purposes and in many different contexts

Knowledge: affordances of genres

Use of the genres in different contexts and with unfamiliar structures and conventions, with teacher modelling and support

Focus: general knowledge of affordances of explanation, reporting, argument/debate and persuasion

See Topics section above

Collaborative process and strategies for constructing knowledge

Collaborative tasks: negotiation of meaning through collaborative talk with peers and teacher; and with teacher modelling

Use of collaborative talk for specific purposes, e.g. to keep the discussion moving

Use of some critical listening strategies, e.g. asking pertinent questions

Analysis of different responsibilities

Use of the genres in different contexts, and unfamiliar structures and conventions, with teacher support, as needed

Focus: as in Year One, with attention to argument/debate and persuasion as more complex genres

See Topics section above

Collaborative tasks: negotiation of meaning with peers, with teacher support, as needed

Use of collaborative talk to construct communal knowledge

Use of extended critical listening strategies, e.g. paraphrasing, defending the ideas of others

Active participation in negotiating and determining responsibilities in group tasks of genres

Year Three

Control of most structures and conventions

Focus: as in Year Two, with attention to argument/debate and persuasion and their pervasive use in society

See Topics section above

Collaborative tasks: control of most meaning-making strategies

Conscious use of negotiation as a way to develop knowledge

Use of critical listening as an essential element in constructing knowledge, e.g. extracting salient points for further elaboration

Evaluation of group performance and effectiveness

Québec Education Program

› 18

Chapter 5

Knowledge,

Processes,

Strategies

Inquiry process and strategies for collecting data

Classroom community

Year One Year Two Year Three

Action research groups: use of inquiry process and action plans to persuade familiar audiences to bring about recommended social change, with teacher support

Use of information-gathering strategies to extend knowledge, e.g. research, interview, ICT

Action research groups: choice of range of issues and more rigorous analysis of problem, with teacher support, as needed

Use of information-gathering strategies to obtain specific knowledge, e.g.

interviewing an expert

Action research groups: choice of range of issues and more rigorous analysis of problem, and with option of further audience

Use of research in constructing knowledge; understanding of the relation of research to social practice

Teacher: models new or difficult processes and strategies, provides important knowledge of the discipline, and promotes a positive learning climate

Peers: share ideas and offer feedback

Use of classroom community support when undertaking activities and projects, e.g. seeking teacher advice when selecting topics for independent units of study and ethnographic research projects

Classroom, school and community resources such as library materials, available technology, and experts in various disciplines

Québec Education Program Languages Secondary English Language Arts

› 19

Chapter 5

Integration of Knowledge, Resources and Strategies

The teacher encourages and supports students as they gradually develop a level of autonomy and a sense of awareness of their abilities as learners. The teacher’s principal means of achieving this goal is to provide the needed structures as students initiate and carry out various projects that demand an integration of their knowledge, resources and strategies. By working regularly in such situations throughout the cycle, students mobilize resources and learn how to reorganize them in new contexts and for new purposes. The Integrated Profile serves as the site for the integration of work from all the competencies of the program. In regular and ongoing conferences with the teacher, students learn to reflect on the processes and strategies they used, and explain how they organized these projects and how they turned out. As students assume personal responsibility for work such as independent units of study and ethnographic research, the teacher negotiates the limits of these projects, taking into consideration the constraints of time and resources, and guiding students to consider projects that are achievable. An important aspect of students’ developing metacognitive abilities is the understanding that constraints change the dynamic of a context, thereby demanding an adaptation of the action being undertaken.

Integration

Independent units of study

Year One

Regular conferences with teacher:

– negotiation of topics, development and basic evaluation criteria

– estimation of duration and scope

– discussion of available resources needed

– identification of constraints

– discussion of adjustments, as needed

See Topics section above

Methods of presentation to suit topics and development, e.g. spoken résumé of units and reasons for choice of topics

Use of rhetorical strategies to engage audience, e.g. humour

Presentation to class outlining research methods and basic interpretation of data

Year Two

Regular conferences with teacher:

– negotiation of topics, development and evaluation criteria

– estimation of duration and scope

– discussion of timeline, management of workload and other constraints

– examination of progress to date in light of constraints and adaptation of projects accordingly

See Topics section above

Methods of presentation to suit topics and development, e.g. use of visuals

Selection of rhetorical strategies for specific purposes, e.g. present a point of view

Presentation to class and/or community detailing methods of research and interpretation of data; consideration of further ways to use the research, e.g. present to other classes

Year Three

Regular conferences with teacher:

– negotiation of topics, development and evaluation criteria

– estimation of duration and scope

– management of workload and other constraints

– reflection on changes to units as they develop and how these changes are being managed

See Topics section above

Methods of presentation to suit topics and development, e.g. multimedia texts

Deliberate use of rhetorical strategies for specific purposes, e.g. persuade to act

Presentation to class and/or community, elaborating on methods of research and interpretation of data; reflection on further uses of the research, e.g. investigate publishing outlets

Québec Education Program

› 20

Chapter 5

Integration

Autonomy

Year One

Focus: drawing on resources needed for developing projects with a certain degree of autonomy, e.g. identifying useful methods for managing workload and setting timelines and deadlines

Seeking teacher guidance and support during projects

Showing creativity in choice of projects and methods of presentation

In new situations, teacher-modelling of analysis of task to discover what knowledge, processes and strategies are needed

Integrated

Profile

(Metacognition)

Focus: in student-teacher conferences, discussing and reflecting on strengths and weaknesses as learner, e.g. identifying what improvements need to be made

Using the Integrated Profile to develop new resources and interests, and for new approaches and ideas

Evaluation of contributions as a team member in collaborative work

Year Two